Like disobedient children, Pluto’s four small outer moons are spinning at inexplicably high rates, apparently defying the steadying influence expected from Pluto and its large partner moon, Charon.

Hydra is the whirling dervish of the quartet, rotating once every 26 minutes.

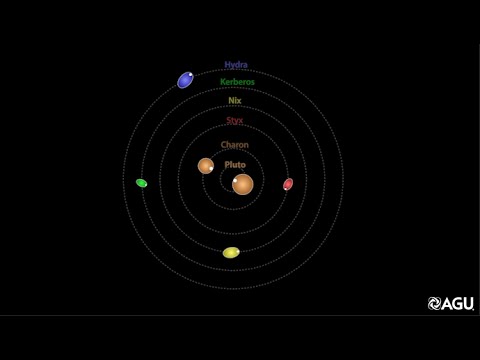

The small moons—Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra, in order of proximity to Pluto—all rotate much faster than the 20 to 38 Earth days the moons take to orbit the Pluto-Charon system, scientists reported Monday. Kerberos spins the slowest, once every 5.33 Earth days, whereas Hydra is the whirling dervish of the quartet, rotating once every 10 hours 19 minutes.

These are fast rotation rates for moons, which usually keep one face pointed at their central planet, rotating just once per orbit of that planet. Earth’s Moon, for instance, rotates once each 27 days 8 hours, the time it takes to orbit our planet once. Among Pluto’s moons, Charon plays by the usual rules, rotating once per orbit of Pluto, but the other, smaller moons don’t.

The Four Tops

“These Pluto moons are essentially spinning tops, and that radically changes the way we understand the dynamics of how they operate,” planetary scientist Mark Showalter of NASA’s New Horizons mission and of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif., told Eos.

“This is unlike anything we’ve seen elsewhere in the solar system,” he added. “No one has ever seen a moon [like Hydra] that rotates 89 times during a single orbit.”

Last July, the New Horizons mission carried out the first ever flyby of Pluto. Analyses of images recorded by the mission’s spacecraft in the weeks leading up to the flyby led to the discovery of the moon’s surprising speeds, unveiled Monday at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences in National Harbor, Md.

Surprising Spin Rates

The push and pull of the gravitational tides of Pluto and Charon ought to have slowed down that motion.

The fast spin rates are so surprising, said Showalter, because even if the moons formed as rapid rotators, the push and pull of the gravitational tides of Pluto and Charon ought to have slowed down that motion.

Instead, “it’s just as if the moons picked some random rate of rotation and Pluto and Charon have no role with any of that,” said Showalter. One possibility, he noted, is that the gravitational tides of Pluto and Charon may work against each other, leaving the moons free to maintain a high spin. It may be like two parents who have given contradictory instructions, leaving their offspring to decide for themselves, Showalter mused.

Among the solar system’s panoply of so-called regular moons—those that form as the result of a collision between a planet and another body—Hydra ranks as the ninth fastest rotator, Showalter said.

This animation shows newly discovered, surprisingly fast rates at which the small moons of Pluto—Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra—rotate and orbit the dwarf planet and its relatively large companion moon Charon. Rotation rates range from once per 5.33 Earth days for Kerberos to once every 10 hours 19 minutes for Hydra. This movie plays at 1.5 Earth days per second. Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Mark Showalter

First Take Revisited

Prior to the flyby, Showalter and Douglas Hamilton of the University of Maryland in College Park had come to a different understanding about the motions of Pluto’s four small moons. Using Hubble Space Telescope images of the moons, they had concluded that the moons rotate chaotically, varying their spin rate and tumbling as they orbit Pluto and Charon. They published their moon motion study in the 4 June issue of Nature.

After examining data recorded by the New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager camera, Showalter, Hamilton, and other colleagues realized that the preflyby explanation was not quite right.

The camera had observed variations in the brightness of the four moons during a 100-day interval that ended early last July. The brightness variations showed clear signs of periodicity, revealing that the moons were not so much tumbling as spinning in a regular fashion, just much faster than anyone expected. The images also reveal that Nix is rotating backward compared to the rest of the Pluto system and on its side.

Fast Times in the Kuiper Belt

Showalter noted that the spin rates of these moons are similar to those of other objects in a vast reservoir of frozen bodies, known as the Kuiper Belt, which lies beyond the orbit of Neptune and which includes the Pluto system. Kuiper Belt objects are thought to have acquired their rapid rotation through collisions with other icy debris in the reservoir. The same may be true of Pluto’s small moons, Showalter suggested.

Because the fast-spinning Plutonian moons are tiny, ranging in diameter from 10 to a few tens of kilometers across, a collision with a large impactor could easily have imparted a lot of spin to the bodies, commented astronomer Scott Tremaine of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., who is not part of the New Horizons team.

From the shapes of the moons revealed by the New Horizons camera, they appear to be mergers of several smaller pieces, indicating that Pluto once had many more moons in its retinue, Showalter said.

—Ron Cowen, Freelance Science Journalist; email: [email protected]

Citation: Cowen, R. (2015), New spin on Pluto’s moons, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO039209. Published on 9 November 2015.

Correction, 24 November 2015: An earlier version of this article gave erroneous information about rotation rates for Pluto’s moons Kerberos and Hydra and about an unusual direction of motion of Pluto’s moon Nix. This article has been updated to give the correct rotation rates for Kerberos and Hydra and to clarify that it is Nix’s rotation that is contrary to that of Pluto’s other moons and of Pluto itself.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.