Humanity’s first mission to touch the Sun could be launched as early as tomorrow morning, on a course to uncover our nearest star’s biggest secrets.

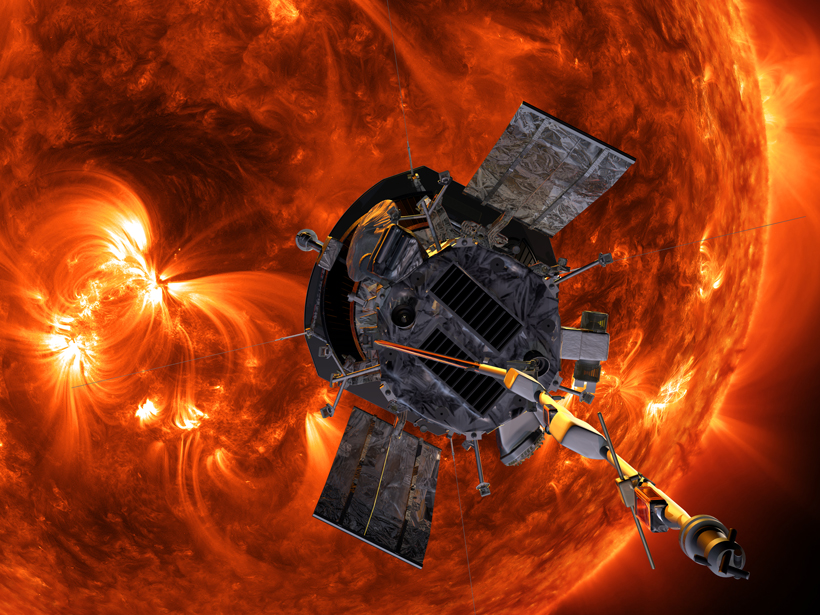

The Parker Solar Probe, built and operated by NASA and the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md., will orbit closer to the Sun than any prior spacecraft.

“We’ve been studying the Sun for decades, and now we’re finally going to go where the action is.”

Just how close? If the Sun and the Earth were scaled to be 1 meter apart, Parker would travel to within 4 centimeters of the Sun. That’s nearly 7 times closer than the previous record holder.

Once there, it will conduct the first in situ measurements of the Sun’s mysteriously hot corona. This outer layer of the Sun’s atmosphere is a diffuse plasma hundreds of times hotter than the Sun’s surface. Scientists, keen to find out how the corona forms and heats, designed Parker to help answer that question.

“We’ve been studying the Sun for decades, and now we’re finally going to go where the action is,” Alex Young said at a 20 July press conference at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla. Young is a solar scientist and the associate director for science in the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Solving Solar Questions

Scientists designed Parker to answer three fundamental questions about our nearest star: What mechanism both heats the corona to 1–2 million degrees Celsius and also accelerates the solar wind to supersonic speeds? What are the structure and the dynamics of the Sun’s electric and magnetic fields? How are charged solar particles flung to speeds that can damage communications systems at Earth?

“We’ve been to every major planet, but we’ve never managed to go up into the corona.”

To answer these questions, Parker is equipped with four suites of scientific instruments. The Electromagnetic Fields Investigation (FIELDS) will map the structure and measure the strength of the Sun’s electric and magnetic fields. The Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe Plus (WISPR) is a visible-light imager that will look at the large-scale structure of the corona and solar wind. The Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) investigation will capture solar wind particles and catalog their properties. Last, the Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun (IS⊙IS, pronounced ee-sis) will study energetic particles released by the Sun to determine what accelerates them to high speeds.

The mission “is a real voyage of discovery,” Nicola Fox, Parker’s project scientist and a space physics researcher at APL, told Eos last fall. Fox is also a member of the Eos Editorial Advisory Board. “We’ve been to every major planet, but we’ve never managed to go up into the corona,” she said.

Just past the corona, “the solar wind suddenly gets so energized that it can actually break away from the pull of the Sun and move out at millions of miles an hour to bathe all of the planets,” Fox said. “You really need to get into [the upper solar atmosphere] to be able to answer the fundamental questions.”

Facing the Heat

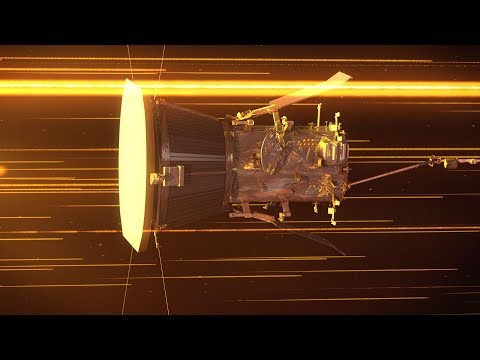

To get so close to the Sun, Parker must withstand the heat. The spacecraft is protected by a heat shield composed of advanced carbon composite materials that dissipates incoming heat before it can penetrate the protective layer. The 2.4-meter-wide, 11.43-centimeter-thick shield also has a white coating to reflect as much of the Sun’s light as possible.

The heat shield can withstand solar radiation that is about 500 times more intense than experienced on Earth. Although the probe will travel through temperatures that average 1,400°C, Parker’s heat shield will let its delicate instruments operate at a relatively cool 29°C, no hotter than a mild summer’s day.

The heat shield technology is revolutionary, Fox explained, and it’s what will allow this probe to survive prolonged exposure to the intense heat and radiation in the Sun’s vicinity. This video explains more about the shield and about other mechanisms in place to help Parker survive the extreme temperatures on approach to the Sun and in its corona:

Closest Approach to Sun in History

The probe will make 24 orbits of the Sun over the course of nearly 7 years. Each of Parker’s orbits will have a perihelion, when the probe will make its closest approach to the Sun for that orbit. Parker’s first perihelion, on 1 November, will occur at a distance of 35.7 solar radii, or about 25 million kilometers, from the Sun’s surface.

It takes approximately 55 times as much energy to reach the Sun as it does to get to Mars and twice the energy needed to reach Pluto, according to mission design leader Yanping Guo of APL. To get around this, the spacecraft will use seven gravity assists from Venus to gradually tighten its orbit. It will make its minimum perihelion at just 8.86 solar radii, or about 6.2 million kilometers, from the Sun’s surface on 19 December 2024.

Parker will get that close to the Sun twice more during the mission. Then, after its final orbit in 2025, it will spiral into the Sun and end its mission.

Parker Solar Probe will be launched no earlier than Saturday, 11 August, at 3:33 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. Its launch window will remain open until 23 August.

This article includes reporting contributions from Randy Showstack.

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer

Citation:

Cartier, K. M. S. (2018), First spacecraft to touch the Sun awaiting launch, Eos, 99, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EO104269. Published on 10 August 2018.

Text © 2018. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.