Editors’ Vox is a blog from AGU’s Publications Department.

Some may think writing or editing a scholarly book is something scientists only do later in their careers after several decades of research, teaching, and other professional experience. On the contrary, two scientists who completed book projects with AGU as early-career researchers found the years right after earning their PhD to be the ideal time to pursue this opportunity. In the first installment of three career-focused articles, these scientists reflect on the positive outcomes the experience had on their professional development.

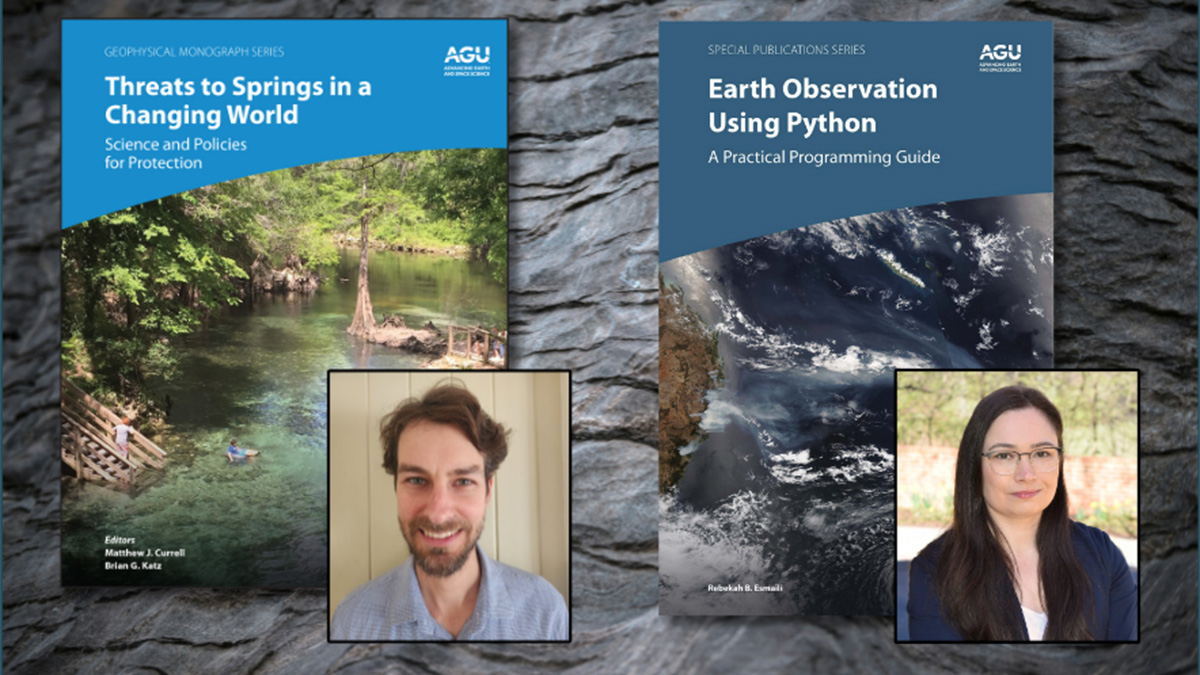

Matthew Currell co-edited the book Threats to Springs in a Changing World: Science and Policies for Protection, which explores the causes of spring degradation and strategies to safeguard them. Rebekah Esmaili authored Earth Observation Using Python: A Practical Programming Guide, a book on basic Python programming to create visualizations from satellite data sets. We asked Currell and Esmaili about why they chose to complete book projects as early-career researchers, the unique strengths early-career researchers bring to such endeavors, and the impacts their books had on their careers.

How would you describe the early-career researcher stage in a scientist’s career?

MC: The first decade of a researcher’s career is a time of great discovery, when the world opens up in front of you. This period can also have its challenges and be quite daunting. It is when responsibility to identify the big research questions of our time, design quality research projects, and start supervising other researchers in training is handed to you all at once. Staying true to the motivations and passion that led you into research in the first place—and making sure you take time to keep listening and learning from those with experience, insight, and knowledge in your field—are key to success.

Even though early-career contributions differ from those of senior researchers, they are still incredibly important for the community to continue thriving.

RE: Early-career researchers are the fresh growth on the knowledge tree, branching out in new directions. They have novel ideas and the enthusiasm to share them, and are quick to learn and adopt new concepts and technologies, so they help the tree gather nutrients and grow. It’s an exciting time to work alongside senior researchers who are astoundingly knowledgeable. A challenge is that early-career researchers may struggle to find their voice; but even though early-career contributions differ from those of senior researchers, they are still incredibly important for the community to continue thriving.

Why did you decide to write or edit a book?

RE: I did not plan on writing a book until I presented a scientific workshop, “Python for Earth Observation,” at an AGU annual meeting. I was inspired to simultaneously teach Python skills while showcasing the visually stunning, publicly available imagery produced by Earth satellites. I initially planned to offer the workshop only once, but the participants’ feedback showed strong interest in the material. Since then, I have presented the workshop every year that I could attend AGU. I decided to write the book to amplify my workshops and to make the content accessible to those unable to travel to conferences. Writing a book appealed to me because books can be widely shared and referenced, and can provide greater detail than is possible during a 4-hour workshop.

MC: The idea for the book first came in an email from my co-editor on the project, Dr. Brian Katz. As soon as I saw the suggested topic on freshwater springs, I was hooked and quickly became determined to make the book a reality. Having spent time with many people, including Aboriginal Traditional Owners from my home country, Australia, I knew how important springs are as a source of water but also a source of life, culture, and connection to the land. I also knew firsthand how many springs were under threat, and how urgent the task was of promoting good science and good policy in the way we manage these springs.

What impact did your book have on your career?

The biggest value and benefit from the book was all the fantastic people and relationships that it helped to build.

MC: I think the biggest value and benefit from the book was all the fantastic people and relationships that it helped to build. For example, the chapter on springs in the Great Artesian Basin at Kati Thanda was very well received by the Arabana Rangers, who are the custodians of the springs and the lands of northern South Australia. This relationship has grown, and now the Arabana Rangers are set to come and present their story of the springs at the upcoming International Association of Hydrogeologists Congress, where I’m organizing the program through the conference technical committee.

RE: Writing a book was a huge project, but doing so helped me master the subject matter, as I had to think deeply about the content and consider how digestible it would be to a new programmer. It also gave me the confidence to take on challenges at work. For example, learning to break down tasks into smaller pieces during the publication process empowered me to apply for larger grants and projects. Project management at work felt less overwhelming because after writing a book, I had experience writing proposals, developing milestones, creating reasonable schedules, collaborating with multiple partners, and delegating chapter reviews.

What were the benefits of completing a book as an early-career researcher, as opposed to doing so at another point in your career?

RE: Early-career scientists can have more empathy for the reader because they have more recent experiences learning new concepts built upon knowledge they have not mastered yet. My awareness of the audience was a strength, and I ended up writing the book I wished I had when I was getting started. I was sensitive to using dense, discipline-specific language that was challenging to understand. Instead, I made a conscious choice to use clear, kind, and encouraging language. If I had written the book later in my career, it might have resembled a traditional textbook, many of which make assumptions about what the reader should already know.

MC: The book helped me to get in touch with many fantastic people around the world working in freshwater springs research, and I had the chance to learn a huge amount from editing the different chapters that present case studies from around the world. These relationships have inspired new ideas and collaborations, and the circle keeps growing —for example, through the global network of researchers called “the Fellowship of the Spring.” Finally, completing a book and seeing it published also brought a huge sense of accomplishment.

—Matthew Currell ([email protected], ![]() 0000-0003-0210-800X), Griffith University, Australia; and Rebekah Esmaili ([email protected],

0000-0003-0210-800X), Griffith University, Australia; and Rebekah Esmaili ([email protected], ![]() 0000-0002-3575-8597), Atmospheric Scientist, United States

0000-0002-3575-8597), Atmospheric Scientist, United States

This post is the first in a set of three. Learn about leading a book project in the mid-career stage and as an experienced researcher.