Scotland contains an amazing array of wildlife; puffins, Scottish wildcats, and orcas all make Scotland their home. But paleontologists David Wacey and Eva Sirantoine weren’t looking for any of these animals; the creatures they were interested in were much, much smaller. They had also been dead for nearly 1 billion years.

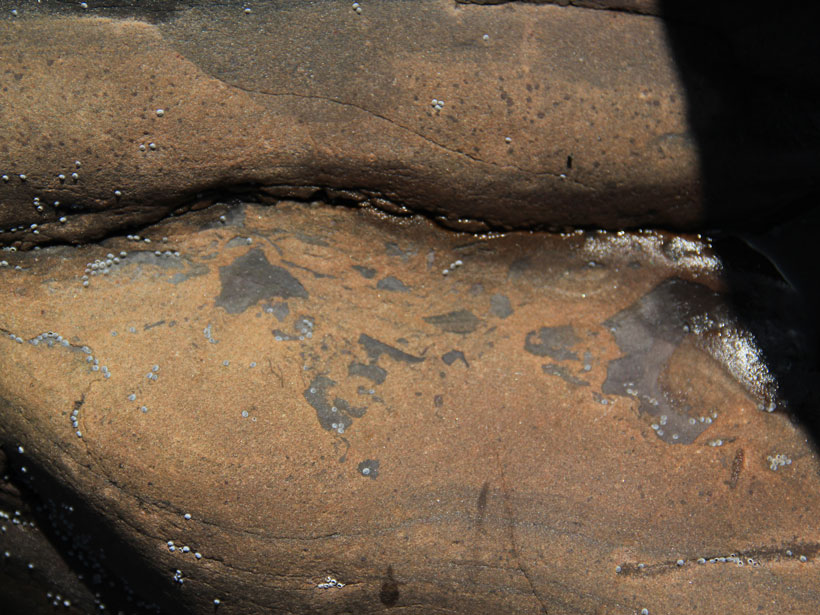

The picturesque sandstone outcroppings of northwest Scotland’s Cailleach Head Formation are studded with tiny gray phosphate nodules. To the casual observer, they might not look particularly special, but in fact, they contain exquisitely preserved microfossils of Precambrian cells.

“Studying this well-preserved deposit gives you a better picture of what the diversity was like.”

In a recent study published in Scientific Reports, scientists from the University of Western Australia and Boston College report that they were actually able to peer inside these ancient cells. Sirantoine says that by using scanning transmission electron microscopy combined with a technique called energy dispersive spectroscopy, the team was able to get an idea of the three-dimensional structure of the fossilized cells as well as to obtain information about the chemical composition of specific regions within them.

Sirantoine says microfossils like these provide us with a window into the distant past. “Most fossils are not as good, so it’s like having a bad camera with a bad lens: You get a blurred image so you can’t really tell what’s in the picture. But when you get very nice fossil deposits like this one, you have a much sharper picture. Studying this well-preserved deposit gives you a better picture of what the diversity was like.”

This group of billion-year-old microfossils contains what appear to be prokaryotic cells (cells without a nucleus) and one cell that appears to be eukaryotic (a more complex cell type that has a nucleus, like animal and plant cells). These fossilized cells were once part of an ancient lake ecosystem.

Preserved by Rare Earth Elements

The researchers think that the cells actively absorbed and retained the rare earth element (REE) phosphates monazite and xenotime. When the cells died, these REE phosphates precipitated rapidly, preserving the inner workings of the cells.

Sirantoine says ancient microfossils can help us understand when and where eukaryotic cells developed and diversified, which was a major step in the evolution of life on Earth.

“That’s what I think is cool about this study—it opens up this new search image, this new place to go look and quest for other preserved fossils.”

Alison Olcott Marshall, a paleobiogeochemist at the University of Kansas who was not involved in the study, says this is an exciting finding. “The farther you go back in time, the fewer rock units there are that are likely to preserve signs of life.…So, we all tend to cluster in the same units because there’s only a limited number of targets. As scientists, we have a sort of search image for what kinds of rocks are good targets. These [samples from the present study] are rocks that wouldn’t necessarily have been somebody’s first place to think of to look. So that’s what I think is cool about this study—it opens up this new search image, this new place to go look and quest for other preserved fossils.”

—Hannah Thomasy (@hannahthomasy), Freelance Science Writer

Citation:

Thomasy, H. (2019), Paleontologists peer inside billion-year-old cells, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO130141. Published on 06 August 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.