Some people travel the world in search of meteorites, prizing these exotic space rocks for what they tell us about our solar system or as collectors’ items. Now an innovative team of youthful meteorite hunters has turned to an unlikely source for determining where meteorites have fallen: weather radar.

Designed to track impending storms such as hurricanes, the technology also reveals the flight paths of meteors passing through Earth’s atmosphere. A group of scientists, educators, and students in the Chicago area is using weather radar data to zero in on a particular burst of meteorites that struck early on 6 February 2017. The space rocks plummeted into Lake Michigan after creating a sonic boom that rattled houses in the area.

Meteors Instead of Hurricanes

“Weather radars aren’t designed to find meteors, but it turns out they work pretty well.”

“Weather radars aren’t designed to find meteors, but it turns out they work pretty well,” said Marc Fries, a curation scientist at NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. In one particular instance, crowdsourced sightings compiled by the American Meteor Society indicated that something pretty hefty hit the atmosphere near Chicago last February.

Fries discussed this meteor sleuthing last week at the American Geophysical Union’s 2017 Fall Meeting in New Orleans, La.

Using data from a nationwide network of 160 weather radars, Fries looked in the Chicago region for the unmistakable signatures of a meteor: an extremely high velocity—several kilometers per second—and a downward trajectory. Pretty much everything else on radar, such as weather, aircraft, and birds, moves horizontally, said Fries. “Meteors fall straight down.”

He soon found what he was looking for: an object whose radar signal suggested it had been roughly the size of a refrigerator and moving at about 20 kilometers per second when it hit Earth’s atmosphere. The extreme heat and pressure of traveling through Earth’s atmosphere shattered it into pieces that continued to travel as a group.

At 1:25 a.m. local time, the signal disappeared over Lake Michigan as the flock of fragments—probably weighing around 100 kilograms in total—landed in 50-meter-deep water.

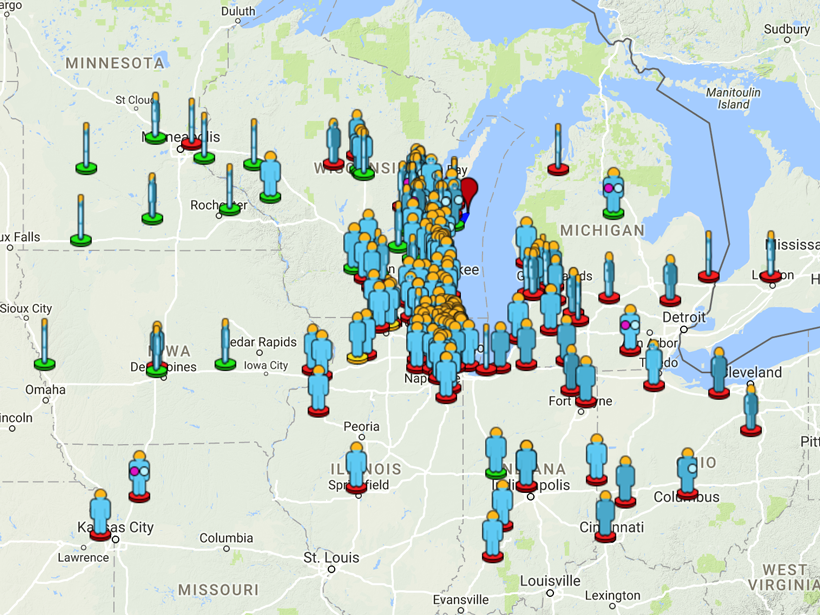

“I’ve come up with a map of not only where the meteorites probably fell but also the expected number and size of them,” said Fries. But radar data don’t reveal precisely where individual meteorites land, Fries noted. “I can’t tell you where one meteorite is…but I can make a map of the strewn field.”

Quick Finds

There’s an advantage to locating meteorite falls using radar data rather than simply walking around looking for space rocks on the ground: It’s relatively fast. (Walking around works well in Antarctica, however, where the dark-colored meteorites contrast with the snow.)

“Searches enabled by weather radar would potentially allow us access to fresh meteorite falls.”

And speed is of the essence for finding meteorites, explained Meenakshi Wadhwa, a cosmochemist at Arizona State University in Tempe who was not involved in the research. Meteorites are relics of the formation of the solar system—their chemistry records the conditions of space when they were formed 4.5 billion years ago—but terrestrial weathering can alter their chemistry significantly, said Wadhwa. “Searches enabled by weather radar would potentially allow us access to fresh meteorite falls.”

Using weather radar data to track meteors is a great opportunity to involve the public in citizen science activities, Fries shared at the Fall Meeting. Moreover, there are many weather radars worldwide that potentially could be used for meteorite hunting, he noted.

A Sled to Find Meteorites

When the Chicago meteor blazed a green path through the sky that February morning, it made news across the city and beyond, and a large citizen science project focused on finding the submerged meteorites has emerged. Known as the Aquarius Project, this collaboration involves scientists and educators working with teen-serving programs at the Adler Planetarium, the Shedd Aquarium, and The Field Museum, all based in Chicago.

Fries shared his map of the likely locations of the meteorites with the Aquarius Project, and teens across the city are now working together to design, build, and test a submersible sled that can be dragged along the bottom of Lake Michigan to retrieve the meteorites that presumably lie in its depths. Because meteorites can contain iron, the students have equipped their sled with magnets to lock onto shards of the extraterrestrial material.

The teens have tested versions of their sled in the water but haven’t yet recovered any meteorites. “Finding meteorites on land is difficult enough,” said Fries. Undeterred, the team continues to anticipate the thrill of locating and retrieving tiny fragments of extraterrestrial rock from the depths of Lake Michigan.

—Katherine Kornei (email: [email protected]; @katherinekornei), Freelance Science Journalist

Citation:

Kornei, K. (2017), Students get help from weather radar to find space rock remains, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO089597. Published on 22 December 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.