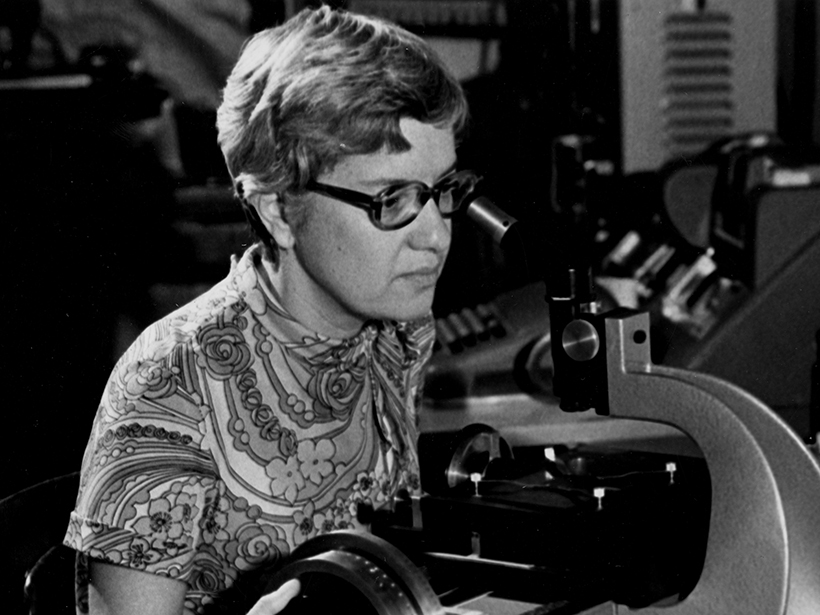

The eminent astronomer Vera Cooper Rubin died on 25 December 2016 in Princeton, N.J., at the age of 88. The far-reaching media coverage of her passing chronicled Vera’s contributions to astronomy, which earned her countless awards, including the National Medal of Science. She, with longtime collaborator Kent Ford, upended what we thought we knew about the universe.

It was not until Rubin and Ford’s work that observational evidence for dark matter’s existence was found.

Their meticulous measurements during the 1960s and 1970s of the orbital speeds of stars in galaxies provided critical evidence of dark matter. Dark matter is invisible. It makes up more than 80% of the mass in the universe. The first inkling of this mysterious material came in 1933 when Swiss astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky of the California Institute of Technology proposed it, and radio observations by scientists, including Morton Roberts and Albert Bosma, during the 1970s advanced the study. But it was not until Rubin and Ford made their observations that most of the astronomical community became convinced of dark matter’s existence.

An Extraordinary Career

Vera was also known for much more. With tenacity, grace, and her signature humor, she was prominent as a passionate feminist and a compassionate mentor.

Vera spent most of her career at the Carnegie Institution for Science (familiarly known as Carnegie Science), which supports research in astronomy, Earth science, and life sciences. Vera worked in Washington, D. C., in the Carnegie Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. Carnegie Science has a tradition of supporting exceptional individuals who pursue research agendas with minimal teaching or administrative duties. That independence to concentrate on science has led to many extraordinary discoveries, as Vera’s dark matter research exemplifies.

“Soon it was more interesting to watch the stars than to sleep.”

Vera certainly was exceptional. In her memoir “An Interesting Voyage,” in Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, she reflected that “as a very young child, I was continually puzzled by the curious workings of the world.” She recalled wondering why, as she rode in her parents’ car, bushes, trees, and houses receded into the distance but the moon stayed “steadily” in the car window.

She remembers that before she was even a teenager, she liked to stare out her bedroom window, fascinated with the night sky. “Soon it was more interesting to watch the stars than to sleep,” she remarked. Not long afterward, her father, an engineer, helped her build a telescope. By her own admission, it “was only a moderate success.” But, by then, the die was cast.

Ironically, Vera enjoyed almost everything about her Calvin Coolidge High School days in Washington, D. C., except physics. The teacher ignored the few girls in the class, she recalled. When Vera was accepted to Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, N.Y.) with a scholarship, she told that teacher her wonderful news. His response: “You should do OK as long as you stay away from science.” Fortunately for all of us, she ignored that sage advice.

Vera graduated from Vassar in 3 years, in 1948, with a bachelor’s degree in astronomy and then married Robert Rubin, who was studying chemistry. She obtained her M.A. from Cornell University (Ithaca, N.Y.), where her husband was, and then earned her Ph.D. from Georgetown University (Washington, D. C.) under the tutelage of the famous cosmologist George Gamow. In 1955, Georgetown offered her a faculty position. She had been conducting research, but she also began teaching and continued both for the next 10 years. Rubin famously juggled her academic career to raise four children, a particularly unusual and difficult feat at that time. All four ultimately acquired Ph.D.’s.

She addressed serious issues of gender bias with good humor—but a strong will.

It was not until 1963 that Vera did her first observing, at Kitt Peak National Observatory, near Tucson, Ariz. By then, she had met the famous Carnegie astronomer Allan Sandage, protégé of Edwin Hubble, also of Carnegie. At an astronomy meeting in 1964, Sandage asked Vera if she would like to observe at the Palomar Observatory, which was closed to women at that time, in Southern California. In 1965, she became the first official female to observe there. She noted that the sign on the door to the one bathroom said “Men.” On a subsequent trip, she drew a woman with a skirt and put it on that door. She addressed serious issues of gender bias with good humor—but a strong will.

Astronomical observing became important to Vera, and she wanted to quit teaching to focus on it. In January 1965, she walked into Carnegie’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism and asked for a job. After Vera collaborated with Ford on a project, the director agreed to hire her with a two-thirds salary that allowed her to leave early to tend to her children. As they say, the rest is history.

A Dedicated Mentor

In addition to her extraordinary scientific accomplishments, Vera had a huge influence on subsequent generations of researchers. A testimonial page was recently set up in her honor. Many former interns and postdocs contributed. What is particularly striking is how little her vast fame affected her, as these few excerpts from the testimonials illustrate:

- “I learned that I would be spending the summer before my junior year of college interning with Vera Rubin, from a voicemail message left by the director….She [Vera] picked me up from the train station, and I remember being so excited and nervous, wanting to impress her. She took me to her house, where I met her husband….The advice she gave us interns was to do what we loved, regardless of what anyone else thought, and to make trouble for the greater good.” —Julia (Haltiwanger) Nicodemus, Assistant Professor, Engineering Studies Program, Lafayette College

- [pullquote float=”right”]“The real prize is finding something new out there.”[/pullquote]“At one point, she [Vera] just stopped and said, ‘Look, you are young. You’ve got a lot going for you and have already contributed to the field.’ She paused for a moment and said, ‘Don’t let anyone keep you down for silly reasons such as who you are. And don’t worry about prizes and fame. The real prize is finding something new out there.’” —Rebecca Oppenheimer, Curator and Professor, Department of Astrophysics, American Museum of Natural History

- “I remember starting my first postdoc at DTM [Department of Terrestrial Magnetism] just out of grad school and being in awe that Vera Rubin was just down the hall from me, but [I was] too nervous to actually talk to her. So one day she simply strolled into my office saying, ‘Hi, I like to meet all the new postdocs around here. I’m Vera.’” —Hannah Jang-Condell, Assistant Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Wyoming

Vera quoted Adlai Stevenson’s tribute to Eleanor Roosevelt in her autobiographical article: “It is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.” She commented, “Astronomers, of course, like it dark.” To me, her comment is an expression of both her humor and how she coped with the many challenges of her life. Enjoy it when it’s dark, especially when bringing enlightenment—which she has done for all of us.

—Matthew Scott (email: in care of [email protected]), Carnegie Institution for Science, Washington, D. C.

Citation:

Scott, M. (2017), Vera Rubin (1928–2016), Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO070407. Published on 29 March 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.