Estimating the price tag of climate change on human health is critical but challenging. Scientists at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NDRC), a United States-based international nonprofit environmental organization, have been working closely with academic partners to paint a clearer picture of these missing health costs.

Their 2011 study was a first attempt to shed light on the scale of health costs related to climate change. It predicted that climate-related extreme events that can harm health were only going to get more frequent and more intense—which is to say, more harmful—in years to come. And they were right: globally, the five warmest years on record all occurred after the paper’s 2011 publication.

While climate change is a global issue, its impacts are localized and personal.

But while climate change is a global issue, its impacts are localized and personal and there is growing demand for specific information on how climate change will impact health in different places. NRDC has been active in translating global warming into a local issue, with a human face.

The latest work is presented in a research article recently published in GeoHealth. It describes ten events in 2012 in the United States, and offers more specific, localized information on the health impacts of climate change, and their costs. I had an opportunity to ask Vijay Limaye and Kim Knowlton, part of the article’s author team, some questions about their latest study and the importance of Earth sciences in offering insights into public health concerns.

Why is it important to estimate the costs associated with climate-sensitive diseases?

Climate-driven health impacts are serious, widespread, and costly—but these damages are largely absent from the policy debate.

Climate-driven health impacts are serious, widespread, and costly—but these damages are largely absent from the policy debate around the costs of inaction and delay on climate change.

Figuring out these costs is challenging because of the array of coordinated data sources — from environmental monitoring and health tracking to healthcare use — that are needed to connect environmental exposures to health impacts to costs.

Our study highlights the importance of supporting coordinated, climate-health monitoring and tracking, to gain a more complete, better-articulated picture of the whole fabric of climate-sensitive events in the United States and their associated costs.

By understanding the local health costs of climate change, there can be more targeted local efforts to avoid the root causes of climate change, and to enhance climate resilience and avoid health harms and their costs, before they occur.

What are some of the challenges to estimating climate-sensitive health costs?

We identified three key hurdles. First, tracking of the range of climate-sensitive health impacts is limited. Many U.S. states are tracking the health impacts of extreme heat exposures, for example, but other climate-driven impacts that are not as obvious — such as the mental health impacts of stronger hurricanes and wildfires — are not monitored comprehensively.

Second, estimating illness costs requires information about specific patient diagnoses, which can be hard to access.

Third, it’s difficult to capture healthcare costs that occur well after a disaster occurs, such as the need for ongoing outpatient care or prescribed medications. Our attention often shifts from one climate change-fueled event to the next, but we really need sustained attention on the ground to better understand the cumulative impacts of increasingly common climate-driven health problems.

What was the focus of your study?

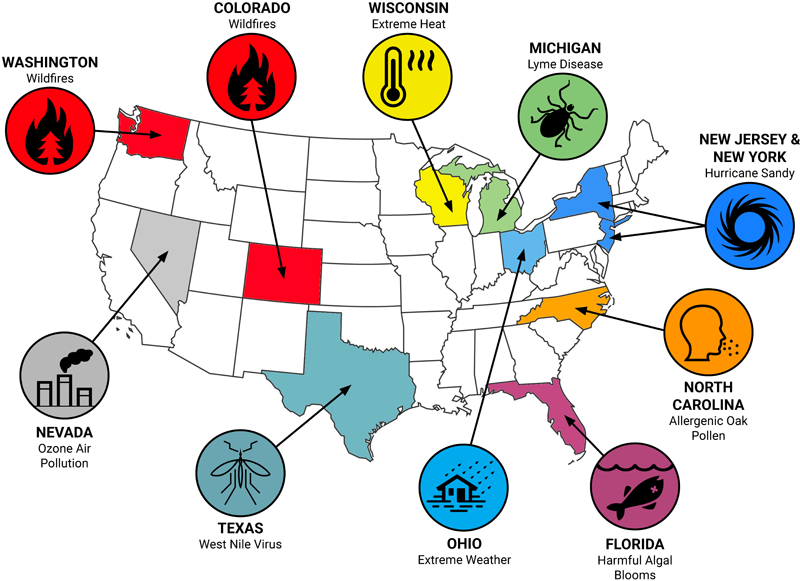

We looked at ten different climate-sensitive events across the United States that occurred in 2012, when the country experienced record-breaking heat. These case study events were diverse in type, intensity, and location: wildfires in Colorado and Washington, harmful algal blooms in Florida, tick-borne Lyme disease in Michigan, Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey and New York, ozone air pollution in Nevada, allergenic oak pollen in North Carolina, extreme weather in Ohio, a mosquito-borne West Nile Virus outbreak in Texas, and extreme heat in Wisconsin.

Climate change is expected to worsen each of those problems in the future, to differing degrees. We were interested in estimating how much these climate-driven events cost us, as a society, in terms of certain health-related expenses: emergency room visits, hospitalizations, lost work days, medications, outpatient care, and premature deaths.

In total, those 10 climate-sensitive events during 2012 led to an estimated 917 deaths, 20,568 hospitalizations, 17,785 emergency department visits, and nearly $10 billion in health-related costs.

For each case study, our team used state-collected health surveillance data, federal reports, and other published data on health impacts to estimate health-related costs.

In total, those 10 climate-sensitive events during 2012 led to an estimated 917 deaths, 20,568 hospitalizations, and 17,785 emergency department visits, along with other health-related expenses, totaling nearly $10 billion (in 2018 dollars) in health-related costs. That’s an astounding price tag, and it only scratches the surface in terms of documented climate-health impacts in recent years.

Were there any findings that surprised you?

We were struck by the many types of health problems linked to climate-sensitive events that extended way beyond what typically comes to mind when we think about the health risks posed by increasing global temperatures.

Our research identified a whole host of illnesses, including pregnancy complications, carbon monoxide poisonings, and kidney disease complications, all linked to the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey and New York.

We were also surprised by the deadly toll of wildfire-driven air pollution, which is estimated to have caused hundreds of premature deaths in Colorado and Washington.

We’ve got to urgently address the root problem of climate change to prevent widespread suffering on a level that we’ve never seen before.

And we doubt whether many people outside Florida realize the number of hospital admissions and emergency room visits there due to harmful algal blooms.

Based on what we know about the data, these examples also signal to us that there’s a whole host of other health problems that are likely hitting people right now, so we’ve got to urgently address the root problem of climate change to prevent widespread suffering on a level that we’ve never seen before.

How does this study relate to our broader understanding of the health impacts of climate change?

While there’s a growing scientific evidence base on the health impacts of climate change across the country and around the world, there’s been less of an effort to stitch together individual events to help us better understand the scale of the overall challenge.

Our work tries to synthesize evidence of the profound and growing burden of climate change on individuals, families, and communities.

Our work tries to bridge this gap by synthesizing evidence of the profound and growing burden of climate change on individuals, families, and communities—especially the most vulnerable among us. Our study was particularly novel in applying recent advances in the climate-health science arena when it comes to the identifying the health impacts of wildfire smoke, allergenic oak pollen, and harmful algal blooms.

We hope that this work will stimulate future efforts to help us better understand the full picture of what’s happening around the world, and ultimately strengthen the case for more ambitious action on climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Earlier you mentioned that the ten events in 2012 generated around $10 billion in health-related costs. Is that the cost of climate change?

No. It’s important to note that our study was not a climate change attribution analysis, and we did not apply statistical modeling techniques in order to definitively link climate change to any particular health harm. Rather, our study is an effort to identify the range of climate-sensitive health problems, i.e. those expected to worsen in frequency, intensity, duration, and/or areal extent in the future due to climate change.

Attributing specific environmental events to climate change is an increasingly precise and urgent science; our endeavor was to synthesize the evidence on climate-sensitive exposures and make the connection to health costs.

We carefully document how each of the case studies in our analysis is linked to climate change and make the case that we’ve already got enough strong evidence about those risks right now in order to act and in order to protect public health.

We also know that far more than ten climate change-fueled events occurred in the United States in 2012, at different scales – regional, statewide, and local. But only about 20 or so states have networks that track any climate-health outcomes. We have a huge opportunity to expand tracking networks and disseminate valuation methods, which would empower local health departments to estimate costs for the most serious local climate-health events. If we knew the whole national health cost burden, there’d be yet another compelling reason to put the brakes on runaway climate change.

What role do the Earth and environmental sciences play in studies like yours that focus on human health?

Advances in the geosciences are crucial for helping to make the connections between climate change, environmental exposures, and human health.

Advances in the geosciences are crucial for helping to make the connections between climate change, environmental exposures, and human health.

As we point out in our study, the data linkages necessary to conduct climate-health impact analyses and cost estimates rely on robust environmental monitoring and health surveillance. Public health protections are only as strong as the environmental data that underlies risk assessments.

We’re living in a brave new world of unprecedented environmental change, and we need interdisciplinary efforts that can effectively connect the dots between those changes and real consequences for human health.

How can the AGU journal GeoHealth help enhance scientific collaboration between environmental and health scientists?

GeoHealth is an opportunity to illuminate links between environmental change and human well-being.

The forum offered by the GeoHealth journal provides a unique opportunity to better illuminate the links between environmental change and human well-being, a topic that’s of vital importance. By bringing together scientists from a range of disciplines, approaches, and geographic areas, the journal can inform urgent policy debates in a robust and timely manner.

Important national and international synthesis reports on climate change, like the U.S. National Climate Assessment, are directly informed by peer-reviewed interdisciplinary science on climate impacts on health. The GeoHealth journal can also help to address important research gaps in this area, by deploying and supporting a growing network of earth and health scientists.

—John Balbus, National Institutes of Health, USA; Vijay Limaye ([email protected]; ![]() 0000-0003-3118-6912) and Kim Knowlton ([email protected];

0000-0003-3118-6912) and Kim Knowlton ([email protected]; ![]() 0000-0002-8075-7817, Natural Resources Defense Council, USA

0000-0002-8075-7817, Natural Resources Defense Council, USA

Citation:

Balbus, J.,Limaye, V., and Knowlton, K. (2019), Putting a price on the costs of climate related health impacts, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO134943. Published on 09 October 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.