From a local municipal contest to a historic presidential race garnering global attention, a quiet and methodical body of constituents works diligently behind the scenes in every U.S. election to ensure a smooth, fair, and safe process. Poll workers are a cornerstone of elections, yet a shortage of volunteers able to serve in these roles increasingly poses a risk to the efficiency of that well-oiled machine.

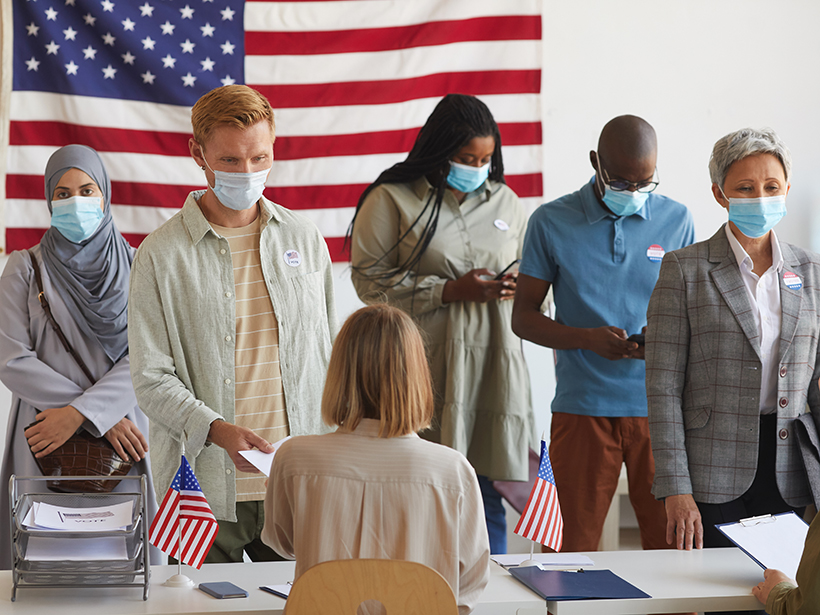

As officials prepared to staff polls for the 2020 presidential election, the COVID-19 pandemic continued to ravage communities and required careful strategic planning to keep voters and staff safe while they cast their ballots. Regardless of stringent safety precautions taken by local elections boards, more than two thirds of repeat poll workers were over the age of 61 and subsequently one of the groups most vulnerable to COVID-19. This meant that many experienced poll workers needed to step back from their positions, increasing the expected number of openings to fill.

Nathan Savidge, director of elections and chief registrar for the board of elections in Northumberland County in Pennsylvania, described obstacles facing more than 70 precincts in his region: “We lost [the participation of] four judges of election the week before the election…. People were scared.” The Pennsylvania Department of State and the local board of elections supplied protective personal equipment and sanitization supplies, but staff were still securing workers just days before the election.

As it happened, I joined Savidge’s team as a first-time poll worker, leading to an experience that I’ll treasure and that I plan to repeat. As a science communicator and member of the scientific community myself, I see a mutually beneficial opportunity for scientists to help with the poll worker gap.

Savidge’s experience was not unique. In fact, while the conditions and risks of in-person voting during a pandemic posed a new set of obstacles in 2020, a shortage of poll workers in U.S. elections is not a new challenge.

A 2013 review of election procedures sparked by the excessively long lines reported in the 2012 presidential race revealed that one of the “signal weaknesses” of the U.S. election system was “the absence of a dependable, well-trained corps of poll workers.” The 2016 presidential election needed the efforts of more than 917,600 poll workers to operate 116,900 polling places nationwide, and in the 2018 midterms, upward of 630,000 poll workers served on Election Day. A Massachusetts Institute of Technology simulation predicted the need for 1.1 million poll workers to support the 2020 election, yet many counties were scrambling to fill vacancies just weeks before this historic presidential election.

A Role for Science at the Polls

Members of the scientific community are uniquely suited to strengthening the U.S. poll-working body, to helping eliminate the shortage, and to ensuring safe and fair elections for all.

Solving the poll worker shortage will require layers of effort and education, and there’s not a one-size-fits-all fix available. However, members of the scientific community are uniquely suited to strengthening the U.S. poll-working body, to helping eliminate the shortage, and to ensuring safe and fair elections for all.

- Scientists can draw on experience from high-stress environments (from thesis defense to fieldwork) to better negotiate and manage situations in which tensions may make efficiency and communication difficult.

- Scientists can adapt the processing and coping mechanisms they’ve honed in the field to rigorous and reliable poll work.

- Familiarity with the scientific method puts scientists in an outstanding position to grasp the crucial concept of process over party.

- Scientists and science communicators remain unintimidated by jargon: Election codes for any given state are often more than 300 pages of legal jargon and can include language carried over from the earliest elections in U.S. history. Scientists have the experience of sifting through similar jargon and as such are in a position to focus on ways to uphold election codes, ensure everyone enjoys a fair and smooth voting experience, provide transparency, and distill accurate and up-to-date information.

Education helps alleviate voter suppression, and members of the scientific community can serve as a trusted and credible source of information. In 2020, there were important changes in election codes related to the pandemic, but in any election it’s probable that many eligible voters haven’t heard all the details, new or old.

Jessica Stancavage, a civics educator in Pennsylvania, shared that for many adults looking for a refresher, “Volunteering at the polls can help us gain a greater understanding of the election process by witnessing it in action.”

If voters are not plugged into their county’s or state’s social media channels or are not regular visitors to their board of elections’ web presence, they may be missing important information. For example, in Pennsylvania, part of the election code requires that new voters provide a form of identification—ranging from a recent utility bill to a state-issued document such as a driver’s license. This kind of information is important to disseminate, and scientists and science communicators can leverage their channels to get the word out.

Poll work is not for the faint of heart.

Poll work is not for the faint of heart—from the moment you walk into your location and take your oath of office, you are volunteering to serve the people and putting into practice all that technical jargon absorbed during training. Savidge compared poll work to a long experiment, with months of planning, education, outreach, and many moving parts leading up to a one-day culmination before the process starts all over again.

The benefits of this service are worth the effort. “Taking this step to help out at the polls can certainly help to spark more interest and participation in the election process,” said Stancavage.

How to Get Involved

Recognizing that the shortage of poll workers in the United States is not going away anytime soon, scientists can mobilize around being part of the solution. In 2020, we saw an enormous push to ensure a safe and fair election that welcomed a record turnout of voters, thanks to many long-standing grassroots efforts. Now is the time to put similar efforts into closing the poll worker gap.

Counties and municipalities across the nation are always looking for people to volunteer to support the electoral process, from local races to those in the national spotlight. Most election officials are local and most polling positions are filled locally, but the best place to start getting involved is through the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. There you’ll find information about state laws and procedures around poll work and can access information about the next election in your area. Another place to look is your county website. Often there is a page specifically dedicated to your board of elections. Reach out to the staff directly and find out when and how you can get involved. You’ll add your voice to those elevating information about election processes, find new connections within your community, and deepen your understanding of the U.S. political process. Likely, you’ll work with people from all backgrounds, coming to the table with viewpoints across the political spectrum.

Immersing yourself in the process of elections can help bolster science policy efforts and help you do what you always do: Filter out the noise and find the truth.

By putting process over party, you’ll work together to ensure a smooth, safe, and fair electoral process for all constituents in your area. If you find great interest in work as a polling clerk, you might also consider running for an elected position in a future race. Your local board of elections can provide more information about appointed and elected positions.

The elections staff provides training for poll workers, but take some time and effort to do more. Scientists can leverage their tendency to ask questions: Be the question asker during live orientations. Dig into the literature and have conversations with people who are veterans of the process.

Ultimately, scientists have a role at the polls, and the benefit is mutual. Immersing yourself in the process of elections can help bolster science policy efforts and help you do what you always do: Filter out the noise and find the truth.

Once you’ve experienced one election cycle, Savidge implores, “Just stay active. Poll workers are probably the most critical part of an election…. [They] help voters sign in, vote, communicate with the public, and explain the policies and procedures.”

Get involved, and see you at the polls!

—Kelly McCarthy (@kmccarthy317), Program Manager, Education and Communications, Thriving Earth Exchange, AGU

Citation:

McCarthy, K. (2021), Scientists are primed for poll positions, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO153578. Published on 19 January 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.