Source: Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences

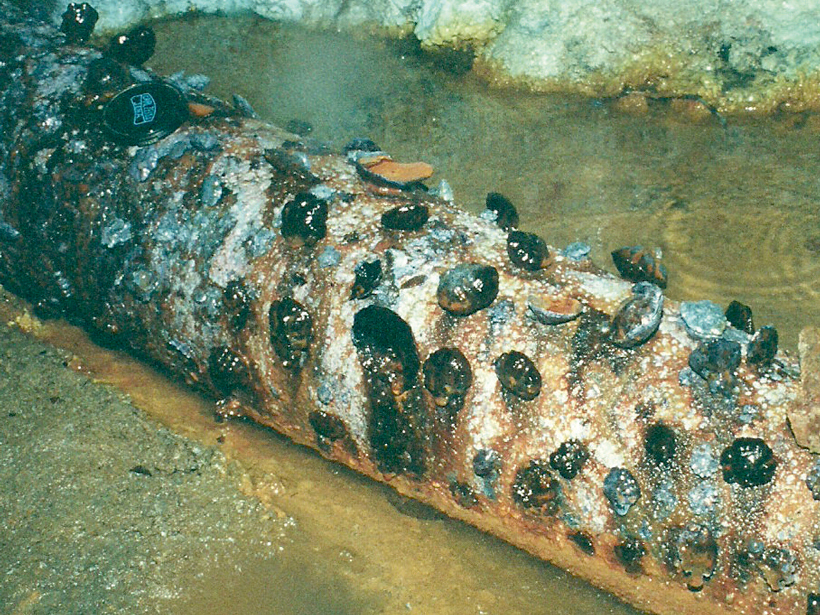

High in the Pyrenees Mountains, deep in abandoned mines, scientists discovered peculiar black shells that seem to crop up of their own accord on metal surfaces. These bulbous protrusions coat steel pipes, cables, and rods left behind by the miners, and now researchers think they know why they form.

Through careful analysis of the shells’ composition and structure, Fernández-Remolar et al. concluded that microbes—fungi primarily—form the shells, depositing iron oxide and other minerals as part of their natural metabolism.

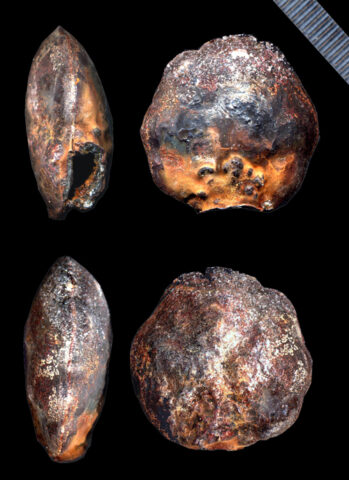

The clam-like structures—composed of an upper and lower shell—have a rough symmetry to them and always grow outward from a single point of attachment. Electron microscopy revealed small-scale, fiber-like crystals arranged into lines growing outward from the steel surface. The shells appear to be formed layer by layer, with crystal size and composition varying across layers.

To determine what sorts of microbes might be laying down the mineral layers, scientists used spectrometric techniques in combination with an antibody-covered chip originally designed to search for life on other planets. Specifically, the team analyzed cave environments by testing for 300 different components of microbial cells, such as DNA, proteins, and other biomolecules, to generate a fingerprint of what sort of organisms might be present.

The researchers report that fungal filaments, which sequester iron ions from the mine waters, appear to be the dominant players in the shells’ formation, especially in the latter stages of development after the base layers have been laid down by bacteria. The result of this complex interplay between microbes and iron-rich water is a rapid biomineralization process that sprouts iron-rich shells from the surface of steel structures. (Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, doi:10.1002/2014JG002745, 2015)

—David Shultz, Freelance Writer

Citation: Shultz, D. (2015) Microbial communities form iron shells in abandoned mines, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO035249. Published on 10 September 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.