The calendar has stopped working for the people of the Pamir—the stunning, stark mountain range straddling the modern-day borders of Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

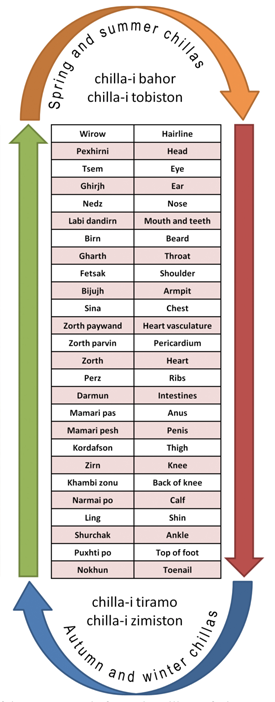

A shifting climate is disrupting not only their subsistence farming and herding but also their unique way of tracking time. Whereas the Gregorian calendar marks a year by 365 days spread across 12 months, Pamiri calendars are driven by observed cues in the environment spread across a calendar of the human body. Local timekeepers name each new seasonal development after a part of the body, beginning with the toenail, then moving upward to the shin, the thigh, the intestines, the heart, and so on, until reaching the head. Arrival at the head coincides with the end of spring and a pause in counting. When the first cue of summer is observed, the counting sequence restarts, but this time from the head downward. Timekeepers rely on natural events—the nascence of a flower, arrival of a migratory bird, movement of fish, breakup of lake ice—as the indicators of seasonal change, not simply the number of days since significant positions of the Sun, Moon, and stars.

For centuries, this indigenous timekeeping strategy has offered local villagers an intuitive context for scheduling day-to-day life, from when to plow and seed to the timing of festivals and other events at the heart of Pamiri society. In recent years, however, climate change coupled with political instability has begun to disrupt the Pamir landscape, throwing these traditional ecological calendars out of sequence—and in need of recalibration.

“In climate change, there are two primary approaches: mitigate or adapt,” said Karim-Aly Kassam, a professor of environmental and indigenous studies at Cornell University who has long worked in the Pamir region. For the people of the Pamir, “given that they are not the primary contributors to the causes of anthropogenic climate change, there’s nothing significant they can do to mitigate. So they have to adapt.”

To help them do so, Kassam has partnered with the Thriving Earth Exchange (TEX) program of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Climate CoLab to find ways to reconcile the traditional timekeeping of the Pamiri with the modern reality of a changing world. TEX brings scientists and communities facing environmental challenges related to natural hazards, natural resources, or climate change together to work to find solutions. The recalibration initiative came from the Pamiri people themselves, who reached out to Kassam for help to reconnect with their heritage of traditional ecological calendars and to adapt to the shifting baselines of climate change.

A Nexus of Change

The collaboration organized by Kassam expects to launch several projects this year to tackle the recalibration. In the meantime, the Pamiri live with a growing sense of unease.

Aloft at 2000 to 3500 meters in elevation, the villages of the Pamir are at the front lines of climate change. As glaciers and snowpack melt more quickly and spring rains become more intense, locals have reported increasing water levels in rivers and lakes. Changes in water and temperature patterns have left villages scrambling to meet earlier starts to plowing seasons and to find alternative crops to grow in low-elevation areas where certain fruits no longer thrive or to take advantage of a newfound ability to grow wheat at higher elevations.

Until recent years, villagers could count on a local leader, a hisobdon, to track seasonal cues such as leaf budding as the first sign of spring. By counting the number of days until the next cue, the hisobdon would track the progression of time and season. With those reliable patterns breaking down, the impacts differ among villages and valleys, but the shared psychological impact is one of anxiety: the inability to anticipate change and plan for each season, Kassam said. This breakdown is particularly debilitating for the people of the Pamir because of their reliance on environmental cues for planning agricultural and social routines.

Kassam is outspoken about the ethical imperative to work with communities like the Pamir. Although rural communities in alpine and polar regions contribute little to climate change, they are among the first to feel its effects, he noted—a consequence, in part, of already living under extreme conditions.

Three-Pronged Approach

Seeking additional resources and collaborators for recalibrating the Pamiri calendar, Kassam and his partner organizations held a research proposal contest. Originally expecting to select just one project, they decided instead to unite three winning proposals into one collective effort.

The projects are expected to begin in mid-2016. Working with local academic and village partners, one team will recalibrate Pamiri body calendars with updated environmental data. Another will try to apply the Pamiri calendar to water and drought forecasts. The third team will conduct a biodiversity and phenology survey to help reconnect Pamiri calendars with seasonal and local shifts in flora and fauna.

“Each [contest] winner had one aspect to it,” Kassam says. “In a true ‘wicked problem’ approach, we said to them, ‘We’d all win if you work with someone else!’” However, any effective plan must ground its strategy in the local ecological and cultural context in which the Pamiri people live, he added: “It has to be cognizant of their reality.”

In March 2016, Kassam’s research team received an additional 1.2 million euros from the Belmont Forum, a collaboration of funders of global environmental change research, to conduct further studies on ecological calendars in the Pamir Mountains of Afghanistan, China, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, in collaboration with Chinese, German, and Italian scholars.

Integrating Cultural Context into Climate Conversations

Kassam is keen to point out that this culturally grounded approach is just as relevant for climate change adaptation in the United States as it is for the Pamir Mountains. Working with people and communities—together in conversation and using their place-based knowledge—offers the best chance for successful climate adaptation solutions. On another traditional ecological calendar project with colleagues at Cornell, Kassam is working in collaboration with Native American communities on the Standing Rock Reservation.

“With wicked problems, scientific expertise is not enough; a diversity of experiences matters and is highly relevant when seeking solutions,” Kassam says. “The AGU audience is central to this conversation. They are important, and they are essential. But they are not the only ones. We still need place-based knowledge. We need to do it together.”

—Ben Young Landis, Freelance Science Communicator/Contributing Writer for Creative Science Writing and the Thriving Earth Exchange; email: [email protected]

Citation: Landis, B. Y. (2016), Villages must recalibrate time to survive in the Pamir Mountains, Eos, 97, doi:10.1029/2016EO050181. Published on 13 April 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.