A dearth of craters and an abundance of youthful ice mountains unveiled yesterday in the first close-up image of Pluto have startled scientists, sparked debate, and intensified a thirst for more images to help explain how this little, old dwarf planet could show signs of relatively recent geological activity.

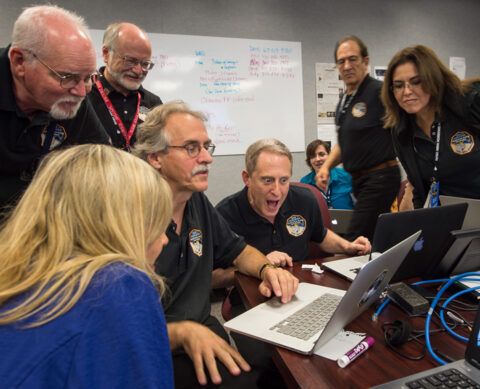

“We now have an isolated small planet that is showing activity after 4.5 billion years,” Alan Stern of Southwest Research Institute (SWRI) in Boulder, Colo., said yesterday at a briefing at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory at which the image was revealed. “We are seeing the fact that these very small planets can be very active after a very long time. And I think it is going to send a lot of geophysicists back to the drawing boards to try to understand how exactly you do that,” he added.

Stern is principal investigator of the NASA New Horizons mission whose spacecraft whizzed past Pluto Tuesday, taking the photo—the first of many to be revealed—that has excited him, other scientists, and the public.

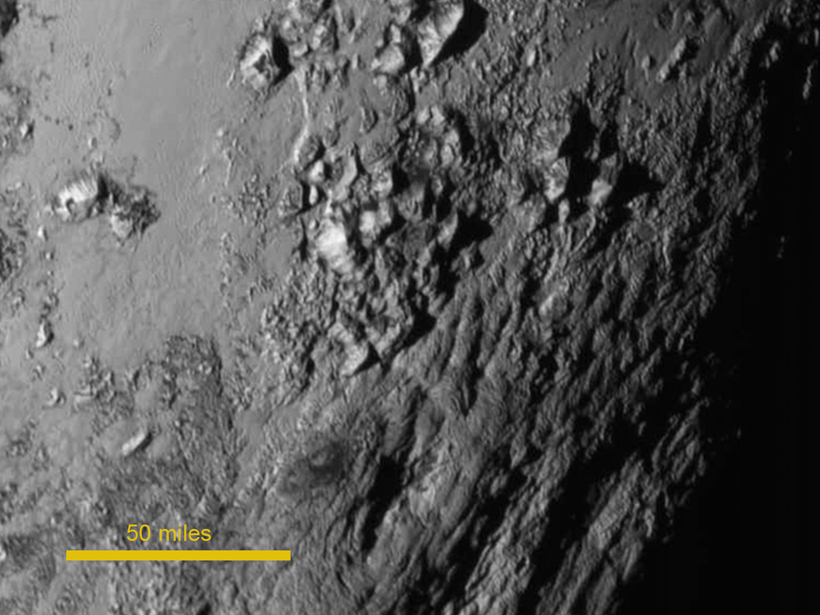

Striking Absence of Craters

The lack of any signs of cratering across a large region of Pluto is the “most striking” new geological finding so far, according to John Spencer, also from SWRI in Boulder and a lead scientist on the mission team. “This means this is a very young surface, because Pluto has been bombarded by other objects in the Kuiper Belt, and craters happen.”

The images of Pluto show regions with an “amazing diversity” of surface composition and geomorphology.

New Horizons coinvestigator Will Grundy said that the images of Pluto to date from the mission show regions with an “amazing diversity” of surface composition and geomorphology. “All of us thought it was probably a few processes that were at work [on Pluto],” said Grundy, an astronomer at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz. “Now it looks like this is a much more complicated system where the interplay of physics and chemistry and thermodynamics is leading to just a huge palette of processes.”

“That, to me, is amazing,” Grundy added. “This is going to keep us busy for a long time to come.”

Spencer was already busy trying to explain Pluto’s surprising topography. Often, strange geological features on icy moons can be attributed to flexing, and therefore heating, caused by the powerful gravity of a nearby giant—an effect known as tidal heating, he explained. But now, “for the first time, we have seen an icy world that isn’t orbiting a giant planet,” Spencer said. Thus, tidal forcing “can’t happen on Pluto. There is no giant body that can be deforming Pluto on an ongoing, regular basis to heat the interior.”

Other potential explanations for Pluto’s geological activity include heat from radioactive elements within the dwarf planet and a reserve of energy stored from Pluto’s formation, he said.

Charon Adds to the Puzzle

Other scientists are trying to make sense of Charon, Pluto’s largest moon, which the mission has also observed, although not as closely as Pluto. One series of troughs and cliffs that extend about 600 miles (970 kilometers) across the moon could be due to internal processes, and the science team will be taking a closer look at that, said New Horizons scientist Cathy Olkin, also with SWRI. “As we have been saying, Pluto did not disappoint. I can add that Charon did not disappoint either,” she said.

After the briefing, Stern noted that discoveries will continue now that the New Horizons spacecraft is “pregnant” with the many data sets it has collected and will transmit to Earth over the next 16 months. “It’s just going to be a really satisfying year and a half.”

—Randy Showstack, Staff Writer

Citation: Showstack, R. (2015), “Amazing” activity evident on Pluto’s surface, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO032899. Published on 16 July 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.