The preservation of Earth and space science data took on even more urgency and relevance at an awards ceremony earlier this month.

The 2016 International Data Rescue Award in the Geosciences, presented during a 15 December town hall at the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU) Fall Meeting in San Francisco, Calif., went to a team of researchers working to preserve historical snow and ice data. These data include historic imagery of glaciers that have since changed dramatically.

The award was announced just 2 days after news broke that some other scientists are frantically copying unrelated U.S. government climate data out of their fear that the data could vanish during the Trump administration. That fear is based in the idea that some likely appointees are climate science skeptics.

“Hearing what is going on right now about data rescue and the fear that data might disappear—I’m very concerned,” said Kerstin Lehnert, director of the Interdisciplinary Earth Data Alliance (IEDA) and senior research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, located in Palisades, N.Y. IEDA and Elsevier Research Data Services organized the award, and Lehnert spoke to Eos at the data rescue award’s presentation ceremony.

Lehnert, who is also the current president of AGU’s Earth and Space Science Informatics (ESSI) focus group, stressed the importance of data preservation. Scientists need “to make sure that the record of the science and the record of observations we do in the Earth sciences is kept for future research and future science,” she said.

Snow and Ice History

This year’s winning project, “Revealing Our Melting Past: Rescuing Historical Snow and Ice Data,” is an effort to digitize the Roger G. Barry Archive at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder. The archive is a trove of snow and ice data in many formats, including prints; images on microplates and glass plates; ice charts from early expeditions to Alaska, the Alps, South and Central America, and Greenland; and handwritten 19th century exploration diaries and observational data.

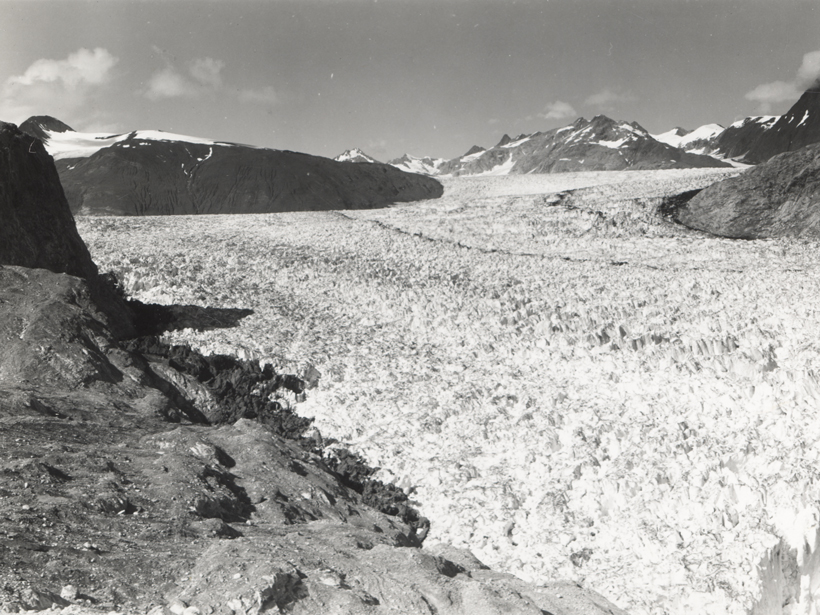

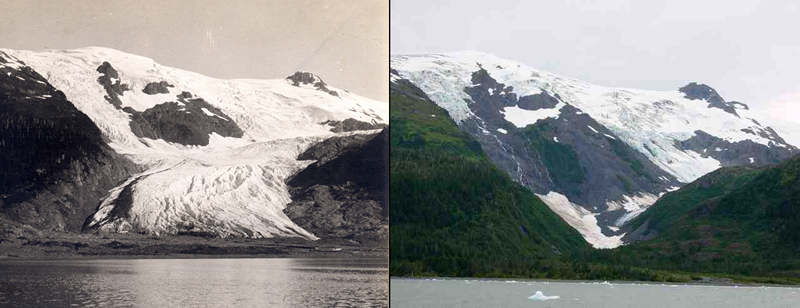

“This is a project that is all about rescuing glacier photos that go all the way back to the late 1800s,” said Ruth Duerr, a project team member who represented the group at the award ceremony. “For science, it is giving you a 150-year record of individual glaciers around the world and how they have changed in terms of mass lost or gained; mostly lost,” said ESSI president-elect Duerr, a research scholar in science data management and software and system engineering at the Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship, which is based in Montclair, N.J.

The project, submitted for the award by Jack Maness, associate professor and director of sciences at the University Libraries at the University of Colorado Boulder, has so far focused on digitizing historical glacier photograph prints, which Lehnert said are fragile, valuable, and unique. The photographs contain rich information on glaciers, permafrost, sea ice, and related data for time periods predating the satellite and digital era, she noted.

The images “are essential to the study of climate change over time and a rich source for the study of our planet and the history of science and exploration, extending our window of analysis,” Lehnert told Eos.

Other institutions involved in the project include NSIDC, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and the Denver Botanic Gardens.

Using the Archive

One researcher who has delved into the NSIDC archive of glacier photos is Bruce Molnia, senior science adviser for national civil applications with the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Va. He has taken updated images of some of the same glaciers that are represented in the NSIDC collection. Some of his images were taken up to 125 years after the original photographs.

Molnia told Eos that his goal was to provide to the archive comparative images of glaciers, so that viewers could clearly see the extent of landscape change. He said that almost every pair of photos shows the transformation of the landscape from white glaciers and dark bedrock to green, heavily vegetated land surfaces and abundant blue water.

“The importance of the NSIDC historical glacier photo collection is paramount,” he said. The collection “is one of a very limited number of venues where an image scientist, or anyone for that matter, can find a rare window into the appearance of Earth’s past landscapes that were dominated by glaciers.”

Raising Awareness of Historical Data

The data rescue award, presented for the first time in 2013, was created to raise awareness about the importance of preserving and having access to historical research data. The award also aims to increase the prospects for preserving the data and showcase the diversity of initiatives that can be adopted to recover and reuse older research data, according to Elsevier, a leading provider of scientific, technical, and medical information products and services.

Historical data at risk could include material that is fragile, has a poor preservation outlook, exists only in hard copies that may not be properly indexed and archived for convenient access and retrieval, or is stored in older electronic formats that may be difficult to retrieve.

Along with award, the team received a $5000 check, which Duerr said will be used to further preservation efforts that could lead to more use of the archive’s materials. “People have a hard time seeing change over their lifetimes,” she said about the historic and modern photos. Now, “they can see change over their and their grandparents’ lifetimes.”

—Randy Showstack (@RandyShowstack), Staff Writer

Citation:

Showstack, R. (2016), Award highlights need to preserve historic geoscience data, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO065569. Published on 28 December 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.