Some birds actively seek to avoid frequent droughts and unpredictable weather, a new study shows.

A large-scale collaboration between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, University of Wisconsin–Madison, and U.S. Geological Survey maps out for the first time how bird populations respond to extreme weather patterns across the United States. The study uses data from a multidecadal ongoing survey that continues to catalog broad populations of birds across vast swaths of North America.

“In the U.S., wildlife managers look for population numbers,” said William Turner, a program scientist at NASA’s Biological Diversity research program, one of the funding agencies for the study. “So this project is particularly important because it’s getting to how those populations and numbers respond to extreme weather events.”

The results give added urgency to mitigate the effects of climate change.

The fact that birds respond to changing weather patterns is well documented, but most of that information is very local. However, the new results show that across the United States, bird migration patterns dramatically altered if paths were blocked by extreme weather, be it drought, heavy rain, or unpredictable winds.

Given that such extreme weather is only likely to increase in a warming world, the results give added urgency to mitigate the effects of climate change, the researchers note. The scientists reported their findings on Monday at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco, Calif.

Stalking Birds Across the Country

The researchers used data from the Breeding Bird Survey, which captures populations of 420 species across North America on a long-term basis. Skilled volunteers drive along 4100 defined routes in the continental United States and Canada every summer, the breeding season for most birds, and stop every half a mile to identify and count bird species.

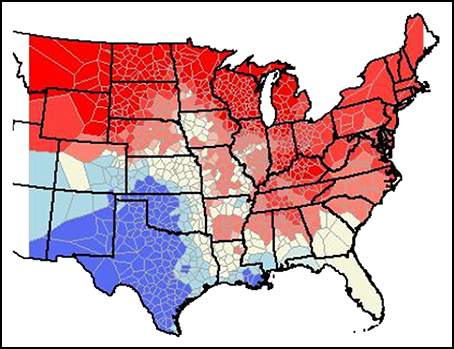

The scientists probed the bird survey data set for 103 species across the lower 48 states, picking only terrestrial birds—skipping seabirds—that are active during the day. They studied how these bird populations moved and how their numbers changed with drought, temperatures, and three major global weather events: the El Niño–Southern Oscillation that seesaws temperature and wind patterns across the tropical Pacific, the Arctic Oscillation of wind-driven pressure changes that circles the Arctic, and the Pacific/North American pattern, which connects climates over the Northern Hemisphere’s midlatitudes.

“We were kind of overwhelmed by how many species had a response.”

The researchers correlated weather data with bird populations and found that 97 of the 103 species were sensitive to at least one of the five weather variables.

“We were kind of overwhelmed by how many species had a response,” said Andrew Allstadt, the lead author and an ecologist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Birds of a Feather Flock in Fair Weather

The responses showed one prevailing trend, at least for birds that are able to fly long distances, Allstadt explained. “We found that most birds aren’t really changing population, but they’re going other places.”

For example, Allstadt and his colleagues found that dickcissels, grassland birds found in central United States, move away from regions where there’s a drought. These birds typically migrate north of Venezuela every year and breed in central United States. But this El Niño year, they changed that pattern: As they flew north from Venezuela, they just stopped when they reached southern United States, which was wetter than usual because of El Niño. There were almost no dickcissels farther north, where they usually go, Allstadt said.

Similarly, wood thrushes in the central United States managed to maintain their populations by contracting their habitat into a smaller area that had good weather.

What About Birds That Don’t Fly Far?

Although birds like dickcissels and wood thrushes maintain their numbers by flying off to better environments, other species, like prairie chickens in the central United States, are less mobile.

Prairie chickens are averse to drought conditions; last year’s drought reduced their population by 30% this year. Although researchers couldn’t say if the birds were breeding less or if they were dying in large numbers, the fact remained that extreme weather caused prairie chicken populations to suffer.

Prairie chickens, then, would be a species you need to manage well because they “don’t have as many alternatives,” Turner said.

In this way, information revealed in the study “helps set priorities [on] which species seem to be particularly susceptible to extreme events,” Turner explained. He noted that targeting preservation efforts to specific species will allow wildlife managers to allocate limited funding resources effectively.

—Devika G. Bansal (email: [email protected]; @dgbansal), Science Communication Program Graduate Student, University of California, Santa Cruz

Citation:

Bansal, D. G. (2016), Birds flock to areas of good weather across the United States, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO064893. Published on 14 December 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.