This morning around 6:32 a.m Eastern time, NASA’s Cassini-Huygens mission finally ended as the Cassini spacecraft melted in Saturn’s atmosphere. Scientists received the loss of signal about an hour and a half later, at 7:55 a.m.

The spacecraft, after orbiting Saturn for 13 years, hit the gas giant 10° north of its equator and disintegrated in the upper atmosphere, 1,500 kilometers above swirling cloud tops. Before its final dissolution, Saturn’s atmosphere ripped the spacecraft apart as it flew in at 113,000 kilometers per hour.

The mission’s end began at 3:04 p.m. Eastern time on 11 September, when a gravitational shove from Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, nudged the spacecraft into its path of destruction.

So long my fascinating friend. Thank you for being spectacularly confusing beyond my wildest dreams. May our paths cross again someday. <3 https://t.co/w5gXjUy06V

— Dr./Prof. Sarah Hörst (@PlanetDr) September 11, 2017

Where to Crash?

Scientists decided on Cassini’s fiery end back in 2014. The spacecraft was running out of fuel, and because Titan or the small, icy moon Enceladus may be potentially habitable, scientists chose to send the spacecraft into Saturn rather than risk having it crash onto either moon—or, really, any of its 53+ moons.

“We don’t want to go back to Enceladus and find [there are] microbes that we put there,” Linda Spilker, head scientist on the Cassini mission, told the Atlantic.

End of an Era

Over the past 13 years, Cassini’s cameras and scientific instruments transformed the Saturnian system from an unknown celestial neighborhood into something “as familiar as your own backyard,” Spilker told Eos.

The spacecraft flew almost 8 billion kilometers in its lifetime, starting with its 3.5-billion-kilometer journey from Earth on 15 October 1997. That lifetime includes nearly 300 orbits of Saturn, with many guided by Titan’s gravity.

It collected more than 600 gigabytes of data. Although that doesn’t sound like much today, consider that Cassini was built with 1980s technology and is still sending us data from 1 billion kilometers away, explained Earl Maize, the mission’s program manager, at a 13 September press conference.

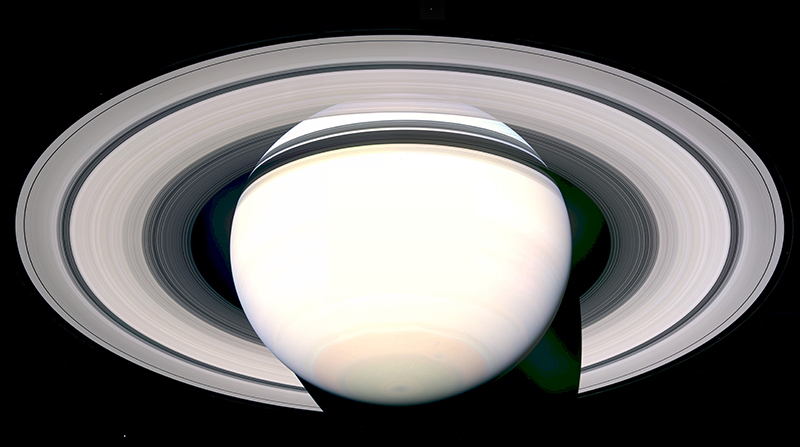

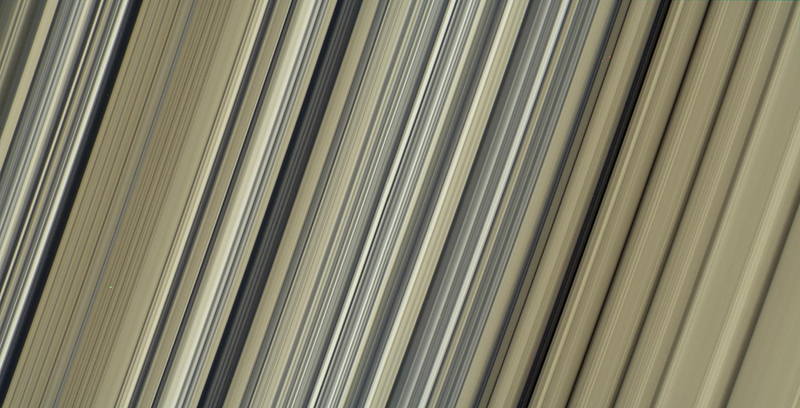

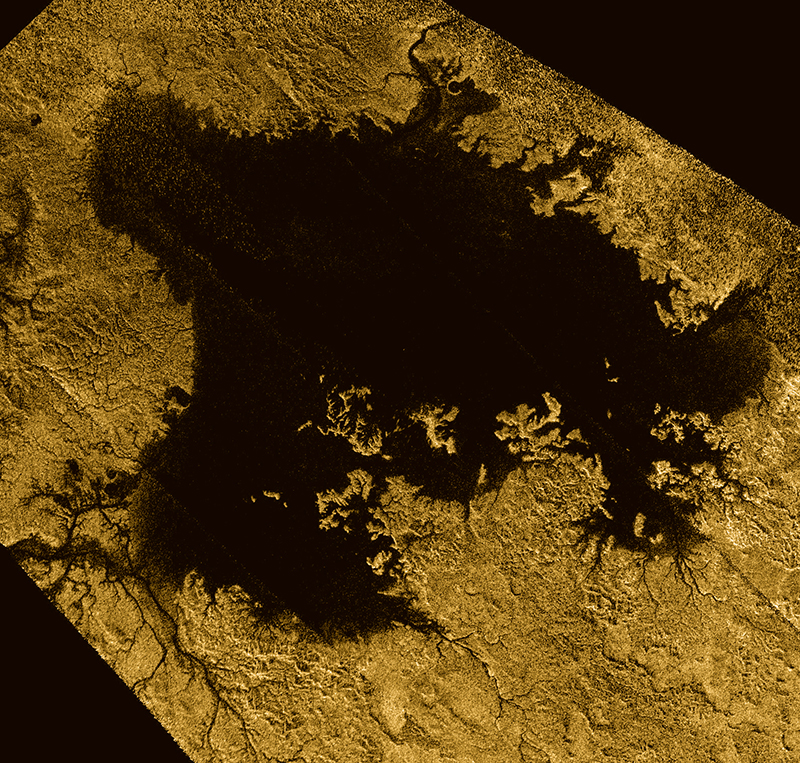

With those data, Cassini helped scientists discover oceans underneath the icy shells of Titan and the much smaller moon Enceladus. There might even be an ocean inside the moon Dione, but data so far haven’t been conclusive. Cassini’s cameras watched waves ripple through Saturn’s rings and storms froth in Saturn’s clouds, spotted six new moons orbiting the gas giant, and showed us a huge, hexagonal jet stream with a hurricane in its center on Saturn’s north pole.

The discoveries led to new questions. How do Titan’s lakes fill up with liquid methane and ethane? Why does Titan even have an atmosphere? What drives the water jets shooting out of Enceladus’s south pole? How did those mysterious red streaks form on the moon Tethys?

After another nudge from Titan’s gravity back in April, the spacecraft spent its last several months rocketing through 22 orbits between Saturn and its dazzling rings. During these grand finale orbits, Cassini investigated Saturn’s magnetic field and the age of the rings themselves, a mystery scientists hope to resolve from Cassini’s last data. The final five orbits even sent Cassini dipping into the tip of Saturn’s atmosphere, where it began sampling a region into which no spacecraft has ever gone.

In Cassini’s final few moments, its mass spectrometer pointed toward Saturn’s atmosphere and collected its clearest data yet. Those data beamed immediately to Earth and were received by a giant antenna in Canberra, Australia, 86 minutes later.

“The spacecraft’s final signal will be like an echo. It will radiate across the solar system for nearly an hour and a half after Cassini itself has gone.”

“The spacecraft’s final signal will be like an echo. It will radiate across the solar system for nearly an hour and a half after Cassini itself has gone,” Maize said in the days before the end.

Final Good-Bye

When she was in third grade, Spilker used to gaze at Saturn and Jupiter with her very own telescope. She always hoped to have “the chance to visit these worlds that were about half a page in my astronomy book.”

And now she and the Cassini team have. What’s more, everyone watching the Cassini mission has shared in that journey.

For Maize, that shared journey is what matters most. “We’ve left the world informed but still wondering, and I couldn’t ask for more,” he said.

—JoAnna Wendel (@JoAnnaScience), Staff Writer

Citation:

Wendel, J. (2017), Cassini plunges into Saturn, ends a 20-year mission, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO082237. Published on 15 September 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.