In the early 1940s, sailors aboard U.S. Navy vessels recorded weather and sea conditions as they cruised the Pacific Ocean during World War II (WWII). After the war, most of these observations languished in classified logbooks for decades and were left out of data sets that formed the backbone of modern climate models. Recently, a crowdsourced science project recovered and digitized these now-declassified meteorological records, rescuing nearly 4 million observations that span a critical wartime data gap.

Before this project, the observations “had never been seen by anybody else except the people who wrote them,” said Praveen Teleti, lead researcher on the project and a climate modeler at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom.

This trove of historical weather data will improve the accuracy of our climate models, Teleti said. “Unless we can be very sure about the historical temperature, we can’t really be certain about how much climate has changed since then.”

Maritime Weather Records

Scientists use climate and weather models to understand how our global climate has changed over the past century, how it might change in the future, and what influences those changes. Those models depend on meteorological records from around the globe and are only as accurate as the data that anchor them.

Observations over land can be collected by weather stations, but the effort is more complicated at sea. In the early 20th century, before the advent of satellites, most maritime weather data were gathered voluntarily by sailors aboard commercial trading ships.

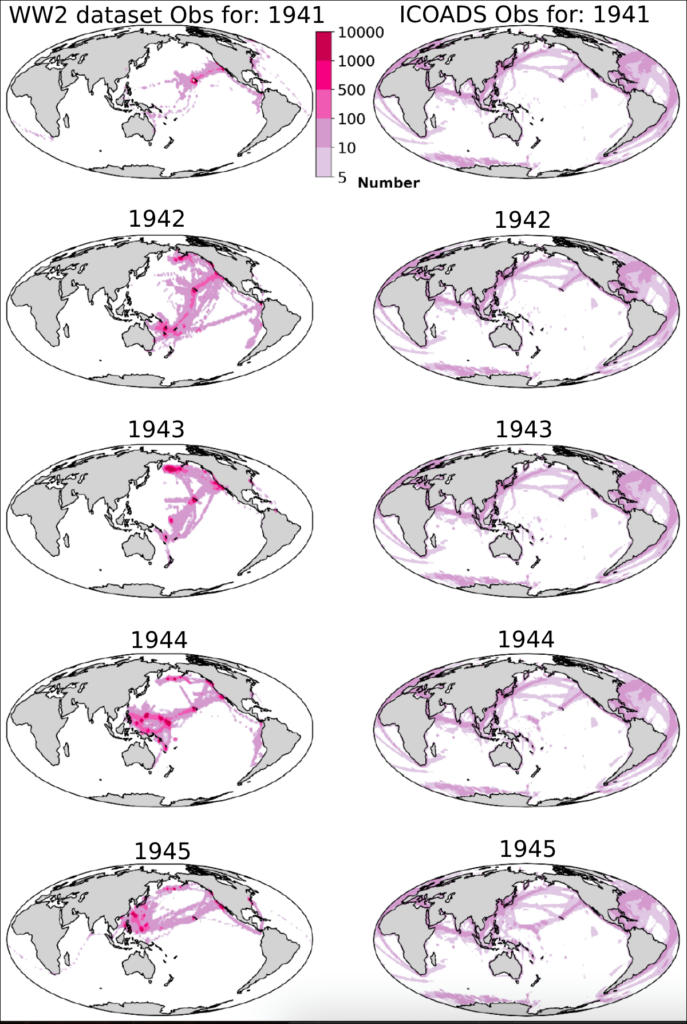

What data we have from that time are limited in their usefulness, Teleti explained. Commercial ships sailed along a few specific routes, and rarely across the Pacific Ocean. Sailors who collected meteorological data did not follow any one standard process, creating unknown biases. And because the efforts were voluntary, they submitted data only sporadically.

“World War II, and other global wars, have been challenging for the availability of environmental observations.”

Moreover, the number of observations from trading vessels dropped precipitously during World War II, especially in the Pacific Ocean, when the few trade routes between the western United States and eastern Asia disappeared completely.

“World War II, and other global wars, have been challenging for the availability of environmental observations due to changes in observing methods, loss of logbooks, and classification of material,” explained Eric Freeman, a surface marine data specialist at NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information in Asheville, N.C., who was not involved with this work.

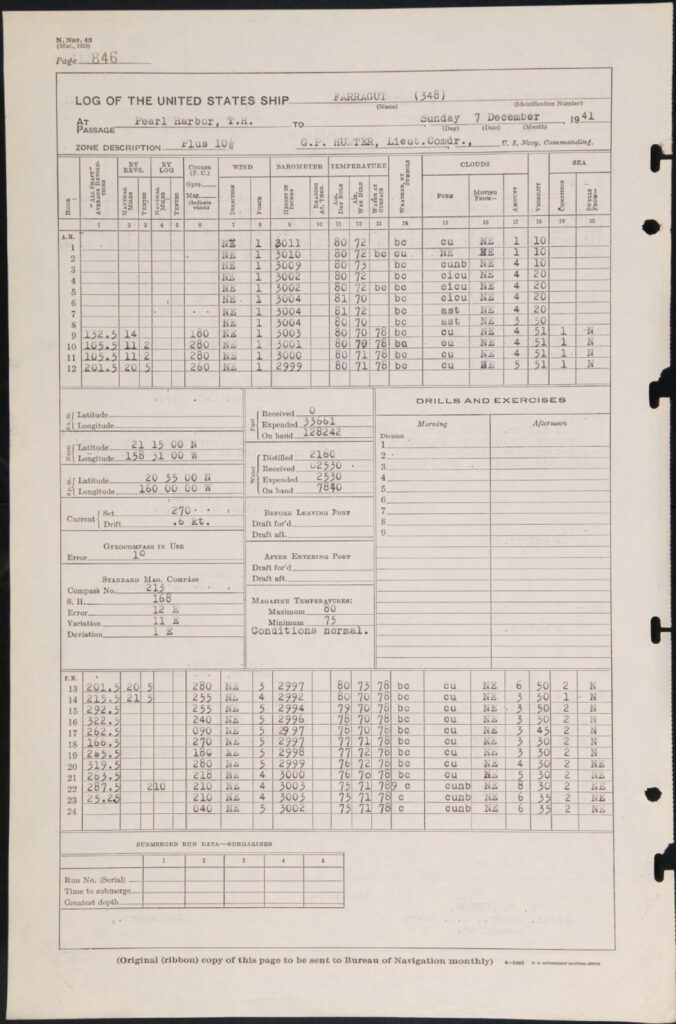

However, there were other ships traveling in the Pacific at that time: U.S. naval vessels deployed after the attack at the U.S. naval station in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941. Navy regulations from the era specified that each ship must log its position and meteorological conditions every hour and detailed the methods a sailor should use to take the observations. (Whether a sailor would follow regulations was, of course, another matter entirely.)

Rescuing Data Lost to Time

For decades, those logbooks were classified to protect military secrets. But in 2017, the National Declassification Center released nearly 200,000 pages of WWII era material, including many from those logbooks.

Available, however, did not mean accessible. Most of the pages remained in paper form in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C., Teleti explained. To access the data they contain, he and his colleagues worked with archivists to photograph and scan each page.

To log the now digital pages, they leveraged crowdsourced science by developing the Old Weather–WW2 project. Participants were presented with images of logbook pages and guided through transcribing ship identifiers, positional information, and any weather observations contained within.

The project rescued 3.7 million meteorological observations that span 1941–1945.

Freeman, who has assisted with other crowdsourced science projects to recover surface marine observations, said these projects can drastically reduce the time and cost to recover historic records. “As long as there is an interest by the public in the data you are trying to digitize,” he said, “citizen science is very effective, highly efficient, and typically satisfies many disciplines, providing a large breadth of public use.”

In total, 4,050 volunteers helped digitize more than 630,000 records from more than 28,000 logbook images from 19 ships. Each record contained multiple types of weather observations, like wet- and dry-bulb temperature, wind speed and direction, barometric pressure, sea surface temperature, visibility, and overall weather conditions. In total, the project rescued 3.7 million meteorological observations that span 1941–1945.

The project took a year and a half, Teleti said. “Thanks, I think, to the pandemic, people were spending more time on the computer, so we wrapped up this project relatively quickly.”

In some areas of the Pacific, these new data more than double the number of weather observations that were previously available. Teleti and his colleagues reported these data in Geoscience Data Journal in September and will present them at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2023 in San Francisco.

“The citizen science aspect of this project is pivotal,” said Duo Chan, a climate scientist at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom who was not involved with the project. “Not only do citizen scientists speed up the conversion of these invaluable historical records, but their efforts also contribute to a valuable data set that can be used to train AI algorithms to perform digitization on even bigger scales.”

Solving WWII Era Mysteries

“These newly recovered observations fill huge voids in the climate record,” Freeman said. “Overall, the better coverage we have, the better confidence we have in how our models perform, and our ability to reproduce past climates is enhanced.”

The team hopes these data will not only improve the overall accuracy of climate reconstructions during WWII but also shed light on an anomalously warm period during WWII.

“They probably never thought 80 years from that time anybody would be looking at these observations.”

Past records suggest that sea surface temperatures during 1941–1945 were notably warmer than the 5 years before and after, but the uncertainty in the data is several times higher during the war than before or after it. No climate model has been able to reproduce this temporary spike in global mean sea surface temperature, Chan said. The ship logs can help depict the climate at that time and improve the models’ accuracy.

The team also hopes the data might help scientists constrain a strong El Niño event that occurred during that decade and understand the nature of Typhoon Cobra, a tropical cyclone in 1944 that sank three U.S. destroyers and killed nearly 800 sailors.

“We were very inspired by the sense of duty [the sailors] had for their work,” Teleti said. “They probably never thought 80 years from that time anybody would be looking at these observations.”

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.