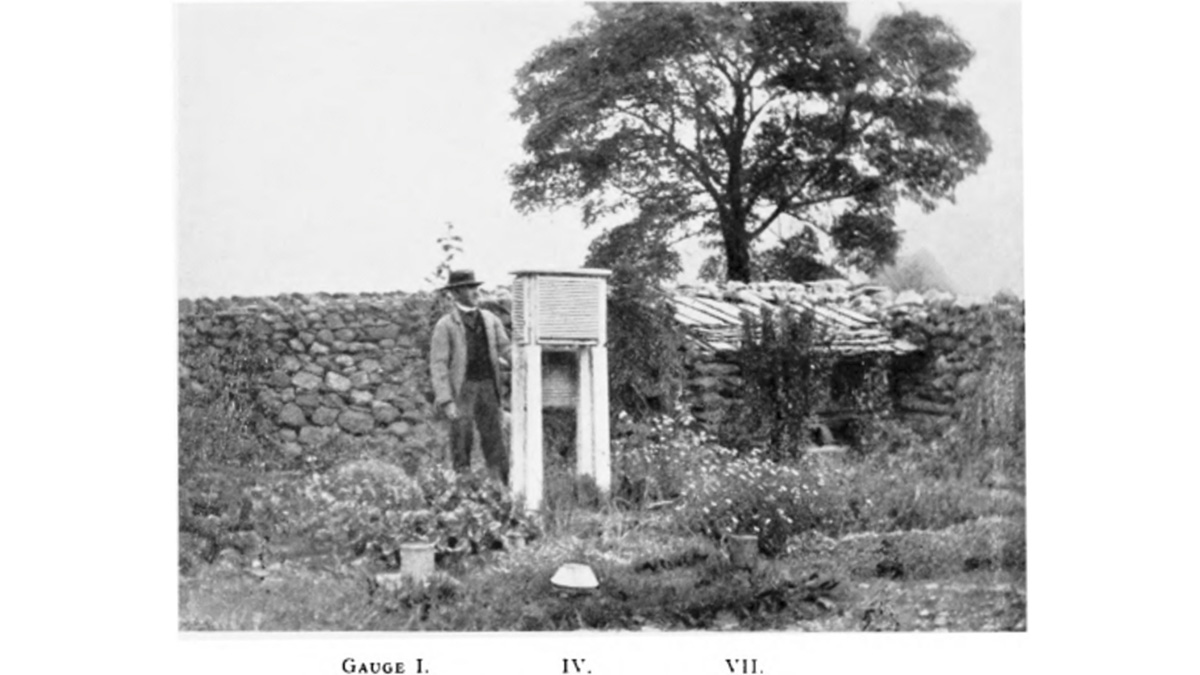

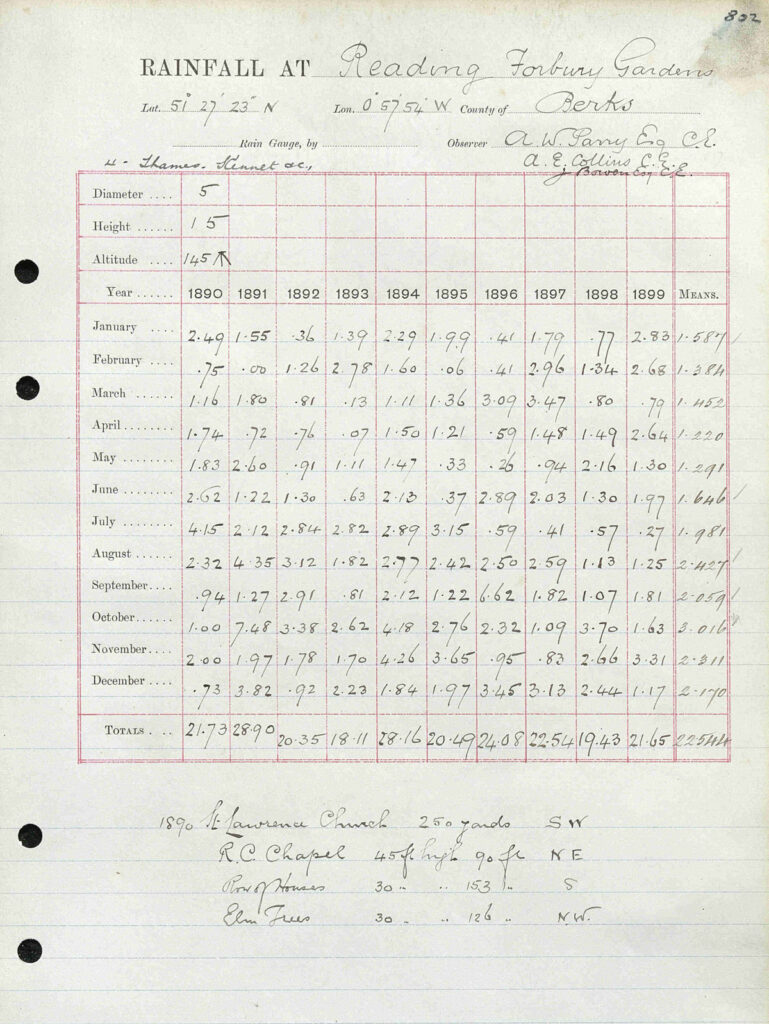

Thousands of volunteers, immobilized by the COVID-19 lockdown, recently revived a trove of historic rainfall records from the United Kingdom and Ireland. The handwritten archives note rainfall observations from landowners, socialites, and an array of eager citizens dating back to the late 17th century. Computer software cannot yet accurately decode handwriting, so human eyes were critical.

Researchers with the Rainfall Rescue project tasked volunteers with manually transcribing 3.34 million observations to make the data available for scientists to study Earth’s past climate.

“We were expecting this to take months,” said Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the University of Reading and lead author of the newly published study describing the effort. “We got through it in 16 days.”

The documents contained enough data to extend detailed weather records back to 1836. In doing so, the researchers crowned the new driest year on record for the region: 1855. “We have rewritten the record books, if you like,” said Hawkins, “by going backwards, not forwards.”

Rescued Records Inform Climate Science

High-resolution weather reconstructions combine meteorological observations with algorithms describing atmospheric physics to iteratively produce a near-hourly estimate of global climate over past decades or even centuries. They are a time machine for climate scientists looking to evaluate long-term trends or interrogate past events. Historic data such as those recovered from the United Kingdom and Ireland can help validate a reconstruction, said Laura Slivinski, a physical scientist with NOAA and the colead on the Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project (version 3), which generated a global atmospheric data set of weather spanning 1836–2015.

Historic data document some particularly extreme events, and that can help scientists understand why and how such events happen, said Drew Lorrey, a climate and environmental scientist at New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. “That’s really powerful, because we can then look in our modern models for similar patterns that are rising months into the future and use that as an early-warning system.”

Records from recent decades show that extreme weather events are becoming more common. “People need to make decisions now about building resilience to the weather in general and how that weather is changing,” Hawkins said. “We need to know what a 1-in-100-year or a 1-in-200-year flood looks like.”

Holes Need Filling

“The further back in time you go, the fewer observations you have, the more work those observations have to do to bring the whole global estimate towards reality.”

Climate reconstructions rely on an enormous database of observations—the bulk of which come from the decades since the proliferation of satellites. Before that time, data are spotty. “The further back in time you go, the fewer observations you have, the more work those observations have to do to bring the whole global estimate towards reality,” said Slivinski, who was not involved with the recent study but works with Hawkins and Lorrey on other projects.

Gaps in climate databases are particularly glaring in the Southern Hemisphere, where there is less land from which to make observations, Lorrey explained. These data rescue efforts are key to filling holes, he said.

Lorrey, who was not involved with Rainfall Rescue, leads the Southern Weather Discovery project, which is recovering early 20th-century weather records from stations in New Zealand and Antarctica and ship logs from ships sailing the Southern Ocean. He and colleagues outlined their approach to crowdsourced record digitization in a paper published in Patterns. Volunteers have so far digitized nearly 250,000 observations from the region.

Although data quality is a concern for the Rainfall Rescue and Southern Weather Discovery records, there’s strength in numbers, said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and lead author of the 2001 and 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports. “An observation not made is lost forever,” he said. “And here, a lot of observations have been made.”

A Shared Experience

Crowdsourced weather data have benefits beyond science. Rainfall Rescue volunteers took to the project’s forums to talk about interesting notes they came across in the records, such as one entry from World War II that mentioned a bullet hole in the rain gauge. Sharing their experiences helped volunteers feel like part of a community, Hawkins said. “There are so many good comments on the chat forums about people feeling useful.”

Modern-day rainfall observers continue to provide precious data. Ongoing initiatives such as the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) have been collecting rainfall data from volunteers in the United States for more than 20 years. The project gives people an outlet for their weather curiosity, said Melissa Griffin, the South Carolina CoCoRaHS coordinator.

And CoCoRaHS volunteers are providing more than just numbers; reports filed during Hurricane Matthew in 2016 include comments about which streets were flooded and where animals were on the move to escape rising streams. That information is valuable for distributing resources in an emergency or estimating future water resources, Griffin said.

“You know you are providing data to your community and your community is using [those] data,” she said.

—Jennifer Schmidt (@DrJenGEO), Science Writer