Dead wood might sound like it belongs in a garbage dump, but it’s a boon to the world’s rivers, beaches, and oceans, where it fuels ecosystem diversity. Until now, scientists have lacked an estimate for how much wood flows through rivers and out to sea. But according to a study reported in Science Advances, some 4.7 million cubic meters of wood may enter the oceans every year as a result of natural process such as erosion and storms. And that amount—almost twice the volume of the Great Pyramid of Giza—may pale in comparison to the wood cascades of the preindustrial past.

Wood at Work in Ecosystems

Before the 1970s, many people thought that the dead wood of old-growth forests was just debris, said Ellen Wohl, a geologist at Colorado State University and one of the authors of the new study. But in the late 1970s, a whole-ecosystem study in the Pacific Northwest started a revolution in how people think about dead wood, she said.

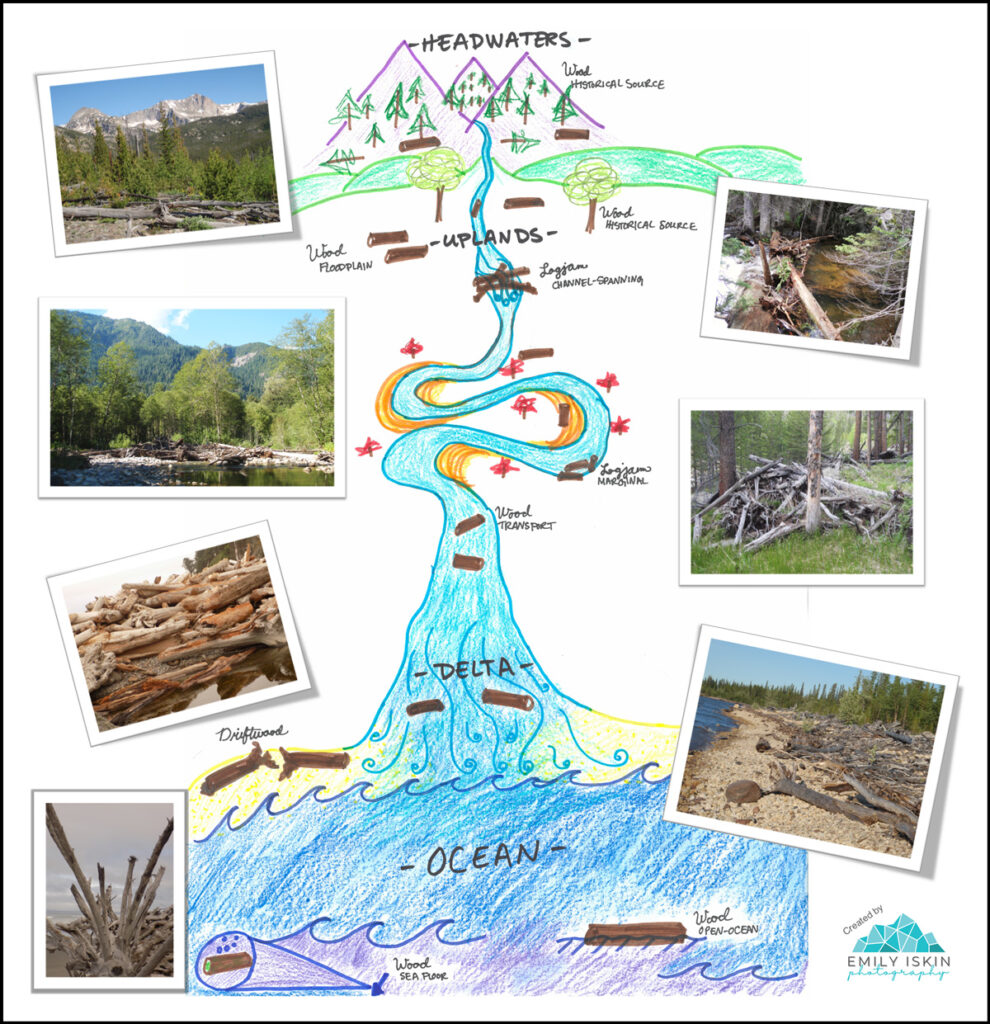

Since then, research has continued to redefine the importance of dead wood to various ecosystems through the creation of habitats and as a source of energy. When wood piles up in rivers, it creates logjams and traps gravel and sand. These events change a river’s shape and flow and create habitats for plants, microbes, invertebrates, and fish. The wood provides energy to an ecosystem at the base of the food web as a source of carbon, said Francesco Comiti, a river scientist at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano in Italy who was not part of the study. A river without wood is much less diverse, he said. Similarly, beach biodiversity is linked to stranded trees. Wood on the shore creates dunes and microhabitats that boost ecosystem diversity.

In the ocean, wood acts as a sunken reef, creating biological hot spots.

In the ocean, wood acts as a sunken reef, creating biological hot spots. Genetic studies have even connected microbes living on mussels in the deep sea with freshwater organisms that live on wood, suggesting that sunken wood may have helped evolve life at hydrothermal vents, “which is just amazing if you think about it,” Wohl added.

For all of wood’s benefits, no one had estimated how much entered the sea on a global scale, so Wohl and graduate student Emily Iskin searched for records of wood exported by rivers. They found a link between a river’s size and the amount of wood it carried. Using this relationship, the researchers predicted the amount of wood that was brought to the sea by 315 of the world’s rivers, excluding ones that export hardly any wood, such as the Nile. The results, which suggest nearly 5 million cubic meters of large wood enter the ocean every year, highlight how wood has been “highly neglected” in river and ocean dynamics, Comiti said.

Modern Changes, Unanswered Questions

Early history may have seen vastly more wood reach the ocean, the authors say. Nowadays, dams cut off river flow and, by extension, the transport of dead wood. People remove wood from waterways for flood control, as well as from harbors, estuaries, and beaches. Plus, deforestation has decreased global tree cover, leading to less wood inputs to the oceans. All of these changes raise the question, What impacts does dead wood’s removal have on coastal, open ocean, and deep-sea ecosystems?

To answer this question and others about dead wood estimates, future studies are necessary. For example, Wohl and Iskin report that the true estimate of how much dead wood is transported by rivers to the ocean likely lies somewhere between 316,000 and 70,000,000 cubic meters per year, but more data are needed. According to Comiti, a better estimate could be reached by weighting each river’s contribution against the amount of its drainage area that is forested. What’s more, the scientists may have also missed significant contributions from small rivers in forested areas that didn’t meet their size threshold.

“I would like people to think about dead wood as a valuable resource.”

Wohl acknowledges the uncertainty—“it’s not so much that I think the actual number is important”—and says it highlights the need for more data. Many countries don’t keep records of wood removed from reservoirs, she said, and for more detailed data, researchers could tag pieces of wood with radio transmitters to provide a picture of how wood journeys through rivers. “I want to increase awareness of this so that people start thinking about it,” Wohl said.

Part of shifting views on wood is changing how people talk about it. She and other researchers have lobbied to drop the word “debris” from the phrase “large woody debris” because of its negative connotation. “I would like people to think about dead wood as a valuable resource.”

—Carolyn Wilke (@CarolynMWilke), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.