Birds use Earth’s magnetic field to navigate. That’s a well-accepted fact. But what aspects of the field they use remain an area of active research, with one of the most intriguing questions being how birds can return to the same location when the magnetic field is constantly in flux. New research suggests birds use magnetic stop signs to return home.

The data showed that nearly all of the songbirds returned to the exact spot where they were born.

Since the early 1900s, birders have been tagging and tracking birds across dozens of countries around the world. From 1940 to 2018, volunteers recorded unique sightings of one type of songbird, the Eurasian reed warbler, nearly 18,000 times during breeding season in Europe. The data showed that nearly all of the songbirds returned to the exact spot where they were born, despite traveling 7,000 kilometers to sub-Saharan Africa for their annual migration.

But in some instances, the birds missed the mark, flying kilometers or more away from their nesting site. The birds’ mistakes were largely skewed toward the shift in Earth’s magnetic inclination, suggesting the birds use this aspect of the magnetic field to find home. Researchers in the United Kingdom and Germany published the analysis in the journal Science last month.

The researchers do not know whether the birds were reacting to magnetic inclination or something related to it. But they know that the recorded sightings matched better with the shifts in inclination rather than with other attributes of Earth’s magnetic field or environmental factors, like temperature. Without conducting experiments, the researchers cannot prove that birds use magnetic inclination to return to their nest.

A Pull of Home

A 2013 study found that magnetic field drift seems to influence where Pacific salmon return to in their home river. And geomagnetic imprinting helps loggerhead sea turtles go back to the beaches where they were born, according to research published in 2018. The latest contribution shows how yet another species uses the magnetic field to find home.

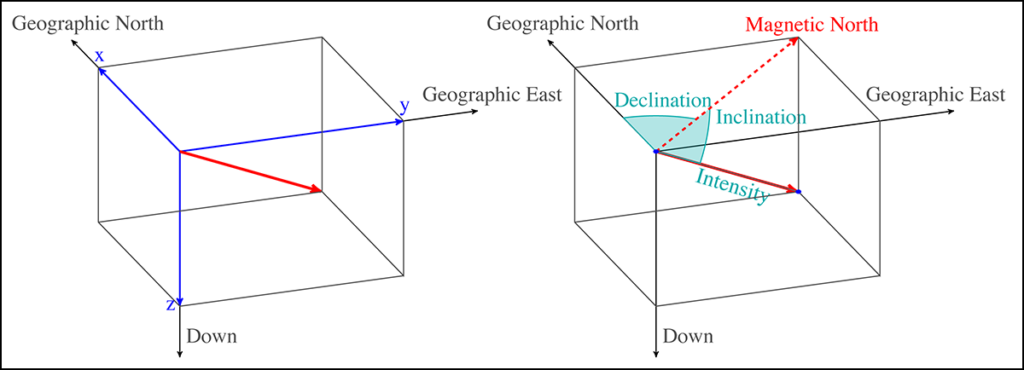

There are three main measurements of the magnetic field that could be used for navigation. First, the intensity of the magnetic field describes its strength at a given point. Second, the declination of the magnetic field shows the angle between magnetic north and the geographic North Pole. Third, the inclination of the magnetic field describes the angle between the magnetic field and Earth’s surface. (At the poles, the inclination is perpendicular; at the equator, it’s parallel.)

They fly along their migration route until they detect the magnetic inclination of their birth site. The scientists called this a “magnetic stop sign.”

Inclination is a great tool for navigation because it roughly mimics latitude—but there are many places on an east-west axis with the same latitude. To get around this issue, the researchers believe that the birds learn the magnetic inclination of their birth site. To return, they fly along their roughly north-south migration route until they detect this inclination. Scientists called this a “magnetic stop sign.”

To test this hypothesis, the researchers looked at historical bird sightings and compared them with a hypothetical random distribution of bird sightings at or near nesting locations. They found that inclination explained the birds’ landing sites better than a random distribution. “When the inclination moves north, they move north, and when it moves south, they move south.”

Inclination did better than declination and intensity, too. Unlike those factors, inclination didn’t correlate with environmental conditions like surface vegetation or temperature.

“Cognitively Pretty Simple”

The idea that birds use inclination was suggested 50 years ago, but there isn’t much understood about birds’ return migration to their nesting sites, said Joseph Wynn at the Institute of Avian Research (Vogelwarte Helgoland) in Germany who authored the work while studying at the University of Oxford. “We’ve got a huge sample size,” said Wynn, “and we can leverage that to get extraordinary statistical power.”

“You can do cutting-edge research and put forward novel hypotheses using historical data collected by thousands of amateurs over many decades, just by using clever analytical techniques.”

“This is a very good example of how you can do cutting-edge research and put forward novel hypotheses using historical data collected by thousands of amateurs over many decades, just by using clever analytical techniques,” said Nikita Chernetsov, director of the ornithology lab at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg, Russia, who was not involved with the research.

“I can see a lot of points that clearly deserve further attention,” he said. For instance, he noted that the observed median change in declination is much greater than that of the predicted random model.

The Earth’s magnetic field slowly changes as molten metals in the core move, but compared with other magnetic parameters, inclination doesn’t change much from year to year. Using inclination as a stop sign moves the target point only about a kilometer each year, compared with using both declination and inclination (which shifts it 18 kilometers) or intensity and inclination (in which it travels nearly 100 kilometers).

Past research has suggested that birds rely on genetically coded migration routes and use all magnetic cues when they’re lost. The latest analysis showed that the mechanism that leads warblers back to their nesting site is relatively simple. The birds remember the inclination of their birth site and fly toward it. “You don’t even need to know how inclination varies on a global scale in order to utilize this,” said Wynn. “It is cognitively pretty simple.”

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), Staff Writer