Nearly three quarters of the world’s fossil fuel carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are from cities. Although cities across the United States and the world are taking the lead on climate action, the amount of CO2 they say they’re emitting is often far too low. This is according to a study published in Nature Communications that examined the self-reported emissions estimates of 48 U.S. cities. Inaccurate self-reporting could undercut efforts to uphold pledges to reduce emissions.

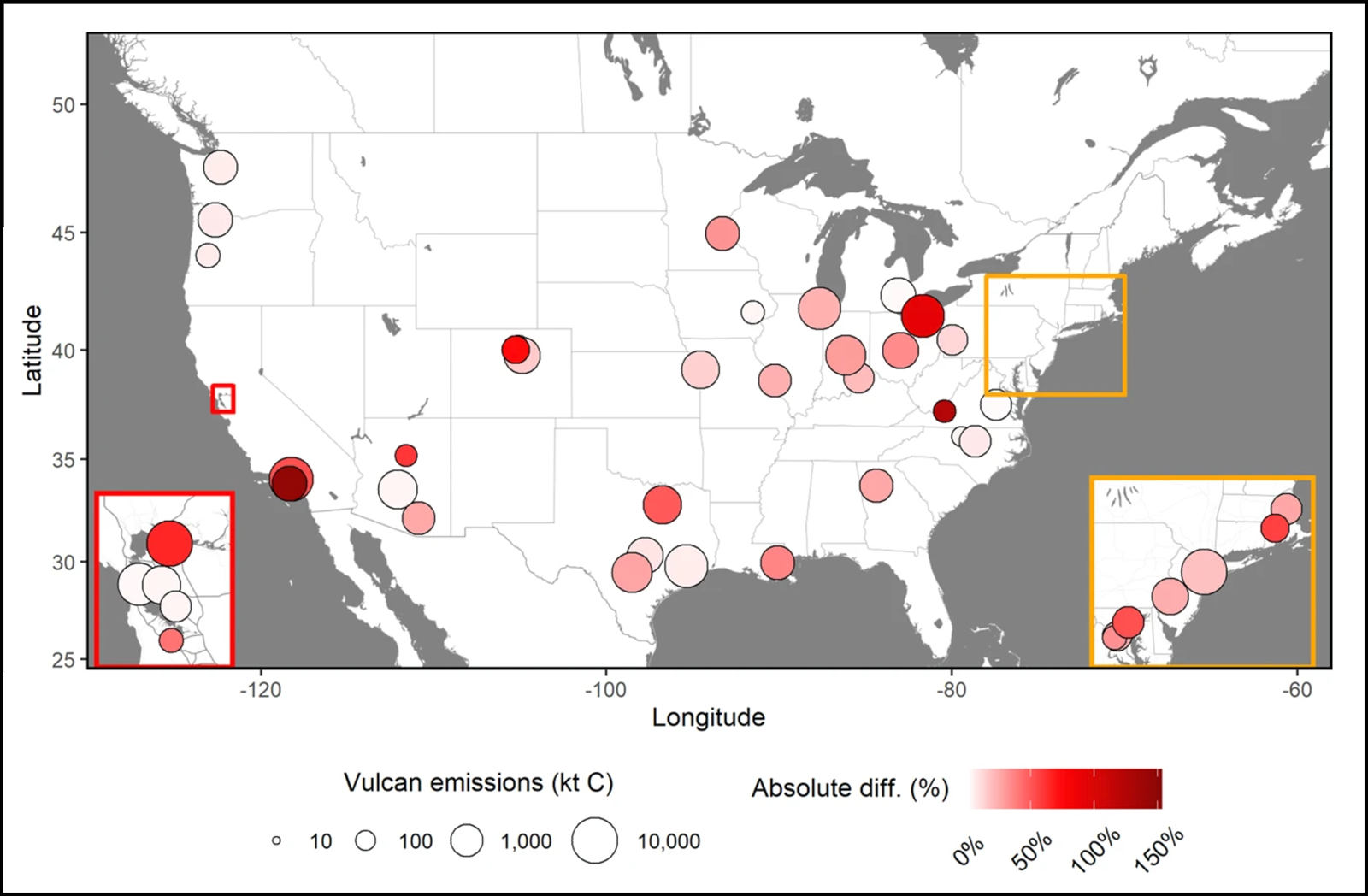

Study authors compared the cities’ inventories with the Vulcan Project, a massive data product that provides all direct fossil fuel CO2 emissions across the United States down to 1-square-kilometer resolution. Between 2010 and 2015, researchers found that the emissions estimated by the municipalities studied were around 20% lower than the Vulcan estimates on average. The disagreement differs greatly by city. Torrance, Calif., was 145% too low, for example, whereas Flagstaff, Ariz., was 60% too high.

“We were really surprised with just the range of how similar or different they were from Vulcan,” said Kimberly Mueller, one of the study’s coauthors and a scientist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the government agency that funded the research.

Gathering Data Can Be Grueling

To self-report all CO2 released directly from fossil fuels, cities must track down emissions from all the myriad sources within their jurisdiction: cars emitting CO2 as they travel, homes heated by burning natural gas or heating oil, power plants providing electricity for residents reading science news online. The city must accurately account for all of these and more.

“Data gathering and processing can be the most onerous part of doing science.”

“Data gathering and processing can be the most onerous part of doing science. You can imagine that being the same in this context,” Mueller said, emphasizing that the researchers found no indication that cities are purposely underreporting their emissions.

The Vulcan Project estimates CO2 emissions from fossil fuels roughly the same way that cities do: by collecting information about emissions sources from utility companies and from public data provided by the government. But Vulcan has several key advantages over the self-reported inventories. First is Vulcan’s “rather neurotic comprehensiveness,” said Kevin Gurney, a professor at Northern Arizona University’s (NAU) School of Informatics and lead author of the study. Vulcan was created with research from Gurney’s lab at NAU. “We really try to get every speck of information that we can.”

This dedicated diligence has led to Vulcan finding hard-to-get emissions often missed by municipalities. For example, heating oil used in industrial and commercial settings is often bought from smaller suppliers. Cities may either have trouble getting that private data or be unaware those transactions are even happening because they aren’t reported by major utility companies.

Second, the Vulcan data have been validated by atmospheric CO2 measurements, a fundamentally different way of estimating the total fossil fuel emissions from the United States. Comparing this technique with Vulcan “provides a degree of independent validation that a standard greenhouse gas inventory lacks,” said Riley Duren, a scientist at the University of Arizona who was not involved in the study. He lauded the study’s rigorous approach to CO2 emissions estimates at such high spatial resolution for the entire United States. “I can’t point to another data product that comes close to doing that.”

“Cities Should Not Be in the Business of Doing Greenhouse Gas Inventories”

None of these results was particularly surprising, said Leah Bamberger, director of the Office of Sustainability for Providence, R.I. Providence’s self-reported inventory was around 60% lower than that reported by Vulcan.

“We’re trying to be accountable and make progress,” she said, but the office’s resources are spread thin. With three full-time employees, it works on an array of issues besides greenhouse gas mitigation, including lead pollution, air quality, and storm water management.

“This is a ridiculous burden to place on cities.”

A regional entity or university working closely with cities, Bamberger said, would be “so much more efficient than every city and town in Rhode Island” trying to build their own inventory of carbon emissions. “Cities should not be in the business of doing greenhouse gas inventories. We don’t have the staff or the resources.”

NAU’s Gurney agrees. “This is a ridiculous burden to place on cities,” he said. Although there are some short-term ways to improve self-reported estimates like using a single standard protocol, an operational data product like Vulcan for the entire United States would be ideal. That way, the study concluded, local governments could “devote time and resource to the activity they have the greatest knowledge and political influence over: the best mitigation strategies for their city.”

—Jordan Wilkerson (@JordanPWilks), Science Writer

This story is a part of Covering Climate Now’s week of coverage focused on “Living Through the Climate Emergency.” Covering Climate Now is a global journalism collaboration committed to strengthening coverage of the climate story.

Citation:

Wilkerson, J. (2021), Many U.S. cities severely underreport their CO2 emissions, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO157512. Published on 21 April 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.