Sprites, elves, trolls, and pixies.

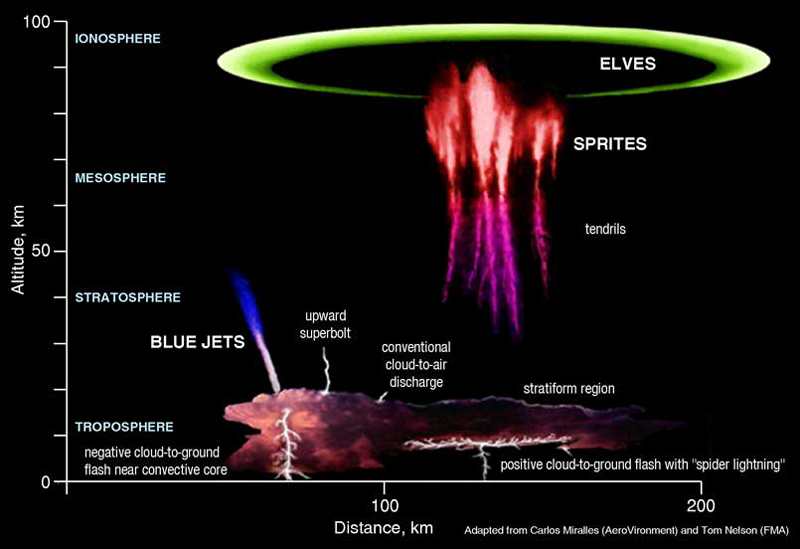

No, we’re not talking fairy-tale creatures. Sprites, elves, trolls, and pixies are all types of transient luminous events (TLEs)—bursts of red and blue light that occur high above thunderclouds and last for as little as a fraction of a second.

Named for their fleeting nature, eyewitness reports of strange flashes above thunderstorms were reported for more than a century before scientists accidentally caught one on film during a test for a rocket mission in 1989. Since then, scientific campaigns have captured stills and high-speed recordings of sprites and other TLEs around the world.

Scientists have many unanswered questions about the phenomena, said Burcu Kosar, a space physicist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Kosar is leading Spritacular, a community effort to build the first global database of sprites and other TLEs for scientific study.

“We need more observations to understand various aspects of sprites and other transient luminous events,” said Kosar. “We may even find new types.”

Spectacular Sprites

“It’s an electrical zoo up there.”

Characteristic examples of sprites include carrots, which look like bunches pulled right out of the garden, and jellyfish with dangling tendrils.

Sprites are generally hidden from view, occurring at an altitude of roughly 80 kilometers. “Electrical activity affects the atmosphere above [the storm], creating various optical phenomena—it’s an electrical zoo up there,” said Kosar, who will be introducing Spritacular on 16 December at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2022.

Whereas scientific efforts to document sprites have declined recently, Kosar said, amateur sky watchers known as “sprite chasers” have been sharing photos of them online for years. The largest group of sprite chasers, the International Observers of Upper-Atmospheric Electric Phenomena, started in 2013 and now has more than 7,000 members.

“Their photos are fantastic,” said Kosar, but “other than a few researchers, the science community is largely unaware of their efforts and observations.”

Kosar, who was previously involved in an aurora-spotting crowdsourced science project, saw an opportunity to create a community where weather photographers and scientists could collaborate. The data and images collected by Spritacular will be used by scientists for new and ongoing research into TLEs.

Knowing Where to Look

Kosar recently had her first sprite-chasing experience with weather photographer Paul Smith in Oklahoma. “We were out night after night scouring the skies,” she said.

The biggest challenge of sprite chasing is being in the right place at the right time, said Smith, who has been photographing the phenomenon for 6 years. Not every storm is going to make a sprite: “It takes experience in reading how storms evolve and the types of lightning responsible.”

“You don’t need specialized equipment to capture a sprite, though,” said Smith, just a standard digital single-lens reflex camera and some practice.

Aside from collecting and collating images, a key aim for the Spritacular project is to support new observers with workshops and educational resources. In addition, Kosar is looking to explore the role of atmospheric gravity waves in sprite formation. Amateur scientists frequently capture sprites and gravity waves concurrently, but more observations are needed to support the idea that these ripples in the atmosphere may help seed sprite formation.

Working Together

“More eyes on the skies will give us unbiased coverage across the globe.”

“More eyes on the skies will give us unbiased coverage across the globe,” said Caitano da Silva, an assistant professor of physics at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology who is not involved in the Spritacular project. “Working together significantly increases our chances of new discoveries.”

Da Silva also hopes the new project will lead to better classification of sprites and other TLEs. Classification so far has drawn on data collected by a small number of research groups.

For amateur scientists like Smith, Spritacular is a “fantastic opportunity to join forces with scientists—if we can analyze each of our shots, just imagine what we might find out.”

For Kosar, the project isn’t just about furthering science. “The study of TLEs in a way started with citizen scientists, and we want to work with them,” she said, adding that there are many ways for people to get involved beyond making observations. “It’s about creating a community. You don’t have to be an observer—you’re welcome on board even if you just want to learn more.”

—Erin Martin-Jones (@Erin_M_J), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.

9 January 2023: This article has been updated to correct references to atmospheric gravity waves.