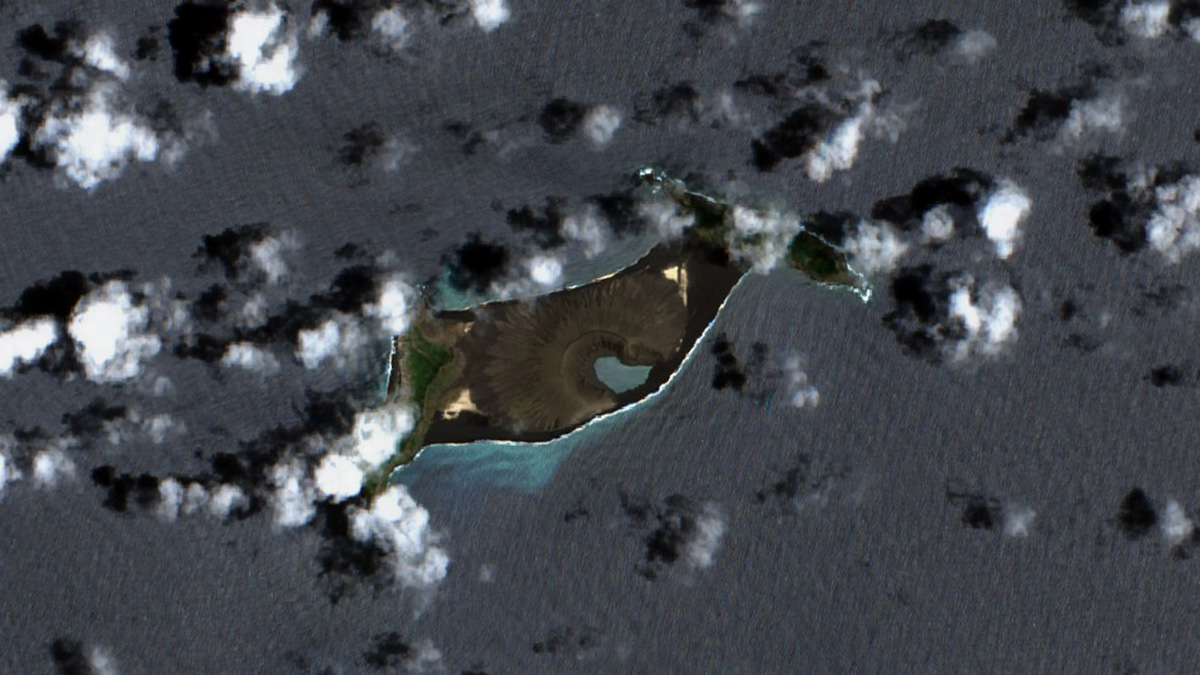

On 15 January at about 5 p.m. local time in Tonga, a massive undersea volcano began to erupt furiously, spewing gas and ash 58 kilometers into the air. It triggered tsunamis nearly 20 meters high, split the uninhabited island of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai into two distinct islands, and led to four deaths. It was the biggest atmospheric explosion ever recorded by scientific instruments.

As dire as the circumstances were, scientists consider it a “near miss.” It lasted only 11 hours and could have been much worse.

“The world is woefully unprepared for such an event,” wrote the authors of a new commentary in Nature. “The Tongan eruption should be a wake-up call.”

They pointed to data from ice cores to say the probability of an eruption happening this century with a magnitude of 7—up to 10 times the size of the Tonga earthquake—is 1 in 6. “Eruptions of this size have, in the past, caused abrupt climate change and the collapse of civilizations and have been associated with the rise of pandemics,” they continued but noted that there is little investment into the forecasting and impacts of such a huge event on transport, food, water, and communication across the globe.

“This risk is not being talked about by our own field; there’s a lot of science out there, but it hasn’t been updated in 20 years.”

Lara Mani had been reading about worst-case scenarios around volcanoes—but the work was written by philosophers, not volcanologists. “It felt like we were being misrepresented,” said Mani, who researches volcanic risk at the University of Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk and coauthored the new paper. “This risk is not being talked about by our own field; there’s a lot of science out there, but it hasn’t been updated in 20 years.”

Mani’s coauthor, Mike Cassidy, a volcanologist at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, started getting interested in large-magnitude eruptions during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. “There was this unprecedented event that started to happen,” he explained, and it made him wonder about how different areas of the world were preparing (or not) for a low-probability but high-impact event.

The researchers point to asteroid collisions as another instance of a low-probability, high-impact event and compared preparedness efforts. Governments and organizations are mobilized to support planetary defense initiatives with financial and infrastructure advocacy, they found. In 2021, for example, NASA launched a $300 million mission to nudge an asteroid out of a collision path with Earth to test future deflection capabilities.

Volcano-Monitoring Satellite

Nothing like this NASA mission exists for volcanoes.

The most powerful eruption in human history was the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, Indonesia. It killed an estimated 100,000 people through pyroclastic flows, tsunamis, and ash. Crops failed after global temperatures dropped, and the resulting famines contributed to the spread of diseases.

The world today is much more interconnected, with a population 8 times larger and 1,000 times more global trade. Financial losses would be in the trillions if such an eruption happened in modern times.

One way to prepare is to monitor volcanoes more closely. The researchers said a dedicated volcano-monitoring satellite would fill many gaps.

“People think the eruptions happen out of the blue, but they’re only out of the blue because we didn’t have enough data or the right data.”

Dedicated volcano satellite missions would be a game changer, said Einat Lev, an associate research professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University who was not associated with the new work. “Sometimes changes in volcanoes happen over years and decades, but sometimes they change over weeks,” she said. A satellite would allow for more continuous observations in a holistic way.

Lev added that more intense monitoring would help address a key misconception about volcanic eruptions—that they are rare. Millions of people live in the shadow of volcanoes in Central America and Indonesia, and better models would be helpful for giving them forecasts.

Lev pointed to the example of weather events and how the ability to predict hurricanes has improved tremendously in the past few decades. “We want to be where hurricanes are with volcanoes,” Lev said, “with multiple models that give uncertainty. People think the eruptions happen out of the blue, but they’re only out of the blue because we didn’t have enough data or the right data.”

“What we are trying to say is this could be a really big destructive event,” said Cassidy. “Pandemics get $10 billion in funding per year, and volcanoes get next to nothing, so we’re trying to look at these global catastrophic risks.”

—Katharine Gammon (@kategammon), Science Writer