Submarines “are roaming the seas around where we are—like flies,” Richard Fodor recalled his older brother Lester telling him about the North Atlantic area where he was stationed on the USS Muskeget. “I’m not too sure about this ship,” Lester confided in his brother. Richard Fodor, who last saw his brother during a visit home to Cleveland, Ohio, in May 1942, recalls Lester telling him that the former Great Lakes freighter was “pretty clunky.”

A few months later, on 9 September, German submarine U-755 torpedoed the ship at its location at Weather Station No. 2 (52°N, 42°W). Lost at sea were 107 enlisted men, 9 commissioned officers, 1 public health service officer, and the 4 weathermen: Luther Brady, George Kubach, Edward Weber, and Lester Fodor.

“I think about my brother every day,” Richard Fodor told Eos, following a 19 November ceremony at the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington, D.C., where the U.S. Coast Guard posthumously presented Purple Heart medals to the four civilian meteorologists. (The USS Muskeget was a Coast Guard vessel.) The occasion marked the first time that U.S. Weather Service employees have received the Purple Heart, a U.S. combat decoration for those killed or wounded in action.

Critical to Winning the War

At the ceremony, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) also presented the meteorologists’ families with commemorative plaques. The weathermen had worked for the U.S. Weather Bureau, the predecessor to the U.S. National Weather Service (NWS), which today is part of NOAA.

“Weather ships and stations became strategic targets for both sides” during World War II.

“Weather observation was a critical element in the Battle of the Atlantic,” remarked NOAA director of maritime heritage James Delgado at the ceremony. “Both sides [in the war] expended considerable effort to establish weather stations and post weather ships in the North Atlantic. And, in consequence, weather ships and stations became strategic targets for both sides.”

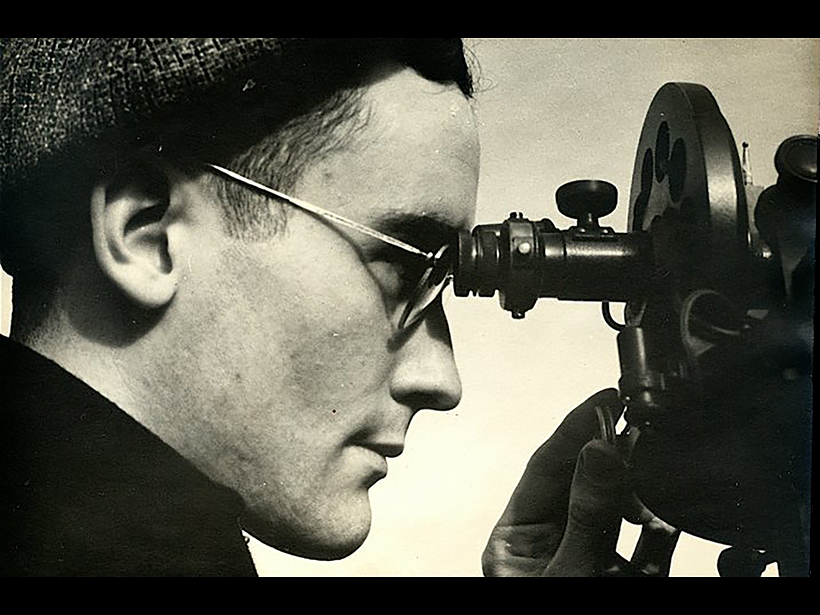

The war took place before satellite systems, GPS, and the Weather Channel, he noted. Weathermen, he said, performed their duties in miserable circumstances: cold, wet, the ship pitching and rolling on the high seas. “In the midst of merely holding on—one hand for yourself, one hand for the ship—to then be looking through a sextant to try to make a weather siting as a balloon goes up, I mean [that is] incredible dedication,” Delgado told Eos.

“He asked me at the end of the call if his brother had made a difference,” Delgado related. “Yes, his brother made a difference.”

The job of calling relatives to tell them about the Purple Heart ceremony had fallen to Delgado. Phoning Richard Fodor, he recalled, had brought tears to his eyes. “He asked me at the end of the call if his brother had made a difference,” Delgado related. “Yes, his brother made a difference.”

Safe Transit

NWS Director Louis Uccellini stressed that weather data collected by meteorologists on the Muskeget and other ships were vital for safe transit on water and in aircraft over the Atlantic. He told Eos that weather forecasts based on observations from other ships provided critical information to convince the Allies to delay D-day from 5 June to 6 June.

Uccellini also drew a parallel between the lost weathermen and the efforts of their modern-day counterparts. Those who study the weather and make forecasts that could save lives and property “are about as dedicated individuals as you’ll ever find,” he said.

—Randy Showstack, Staff Writer

Citation: Showstack, R. (2015), Purple Hearts honor four meteorologists killed in World War II, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO040247. Published on 24 November 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.