Batman, Superman, Jessica Jones, and the Oracle. These and other Marvel and DC superheroes are constantly on alert to protect the world from a rash of cartoon villains. But, yikes, look at some of the gigantic carbon footprints resulting from their superpowers and super gadgets. Can’t superheroes fight evildoers while also cutting down on their greenhouse gas emissions?

That’s the tongue-in-cheek premise of a poster, “Stop Saving the Planet! Carbon Accounting of Superheroes and Their Impacts on Climate Change,” presented this afternoon at the American Geophysical Union’s 2017 Fall Meeting in New Orleans. The poster is part of a session on using real science to explore fictional worlds.

“If I calculate my own carbon footprint, that’s depressing. If I calculate Batman’s carbon footprint, that’s hilarious. So let’s go with the hilarious.”

The point is to get people interested in learning about their own carbon footprints, or how much greenhouse gas they’re responsible for releasing to Earth’s atmosphere each year through their energy use, transportation, diet, and other factors, poster coauthor Miles Traer told Eos. The self-professed comic book nerd and his coauthors are doing that “by using comparisons to things that are admittedly somewhat ridiculous, but things that are very familiar in popular culture,” Traer explained.

“If I calculate my own carbon footprint, that’s depressing. If I calculate Batman’s carbon footprint, that’s hilarious. So let’s go with the hilarious,” said Traer, a geological data scientist doing postdoctoral research at Stanford University. “It’s a way of tricking people into learning.”

Calculating Superhero Carbon Footprints

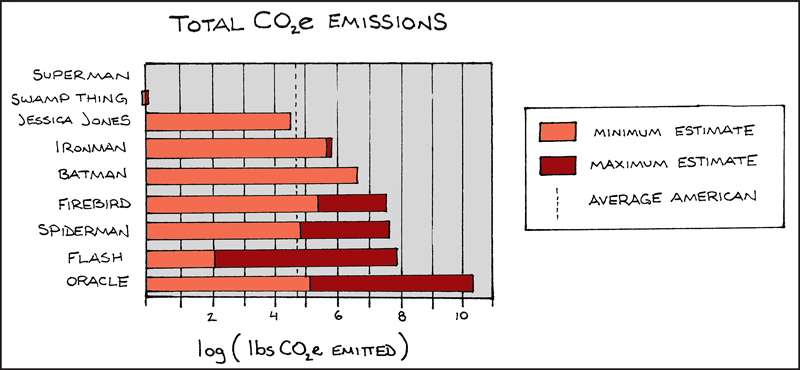

Traer, 35, said that the scientific literature about the average carbon footprint of Americans and media coverage of the topic indicate a figure of about 44,000 pounds per year. (Eos usually uses metric measurements, but the editors have opted in this article to keep the English units as presented.) By comparison, the carbon footprints for some superheroes are supergigantic, according to calculations by him and his coauthors. Traer came up with the numbers with coauthors Ryan Haupt, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wyoming and a paleontologist, and Emily Grubert, a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford and expert in life cycle assessment.

The team found that Batman’s annual carbon footprint is 5.5 million pounds, according to Traer, who noted that many assumptions went into the calculations. For example, the Caped Crusader’s Batmobile emits 48,400 pounds of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) if he drives 20,000 miles per year and gets 8 miles per gallon. That’s assuming Batman drives about the same distance as a New York City cabdriver with the same fuel efficiency as the U.S. presidential limousine.

The Batwing airplane, if used just 48 hours per year, mostly flying rather than hovering, accounts for 1.7 million pounds of CO2e, assuming that its closest real-life analog is some sort of cross between an F-117 stealth fighter and the Harrier Jump Jet. Meanwhile, the Batsuit, which Traer estimates may be Kevlar and Nomex material, requires nearly 7,000 pounds of CO2e to make.

“I’m not saying that superheroes are bad,” Traer commented, insisting that he is “absolutely pro-superhero.” “What I’m trying to point out is, hey, how can we improve their carbon footprint. Let’s say, ‘Hey Batman, you’re driving around in this behemoth car; maybe have some regenerative braking, maybe have a hybrid engine of some kind.’”

Batman Versus the Environment?

Traer, who has a collection of hundreds of comic books, said that the poster project began with Batman. A few summers ago, he and some friends were hiking in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range, debating who is the best superhero. Traer insisted that it’s Batman. But then, as Traer recalled, a friend turned to him and said, “Miles, you’re a hypocrite. You’re an environmentalist. Batman has got to be terrible for the environment.”

“I kind of chuckled,” Traer said, “and, in the back of my head, I was like, ‘I bet I could calculate that.’”

For the poster project, Traer and coauthors also calculated the footprints for eight other superheroes, again with enormous assumptions. Carbon emissions for the Flash, for instance, ranged from a meager 131 pounds of CO2e to nearly 89.5 million pounds, depending on factors including his running speed—which Traer said could be near the speed of light—and CO2e per calorie in his diet. The carbon footprint for Oracle, a computer whiz, also varied wildly, depending on assumptions such as computer energy sources, from about 151,000 to more than 320 million pounds. Most of the footprint for Oracle, who works alongside Batman, comes from the massive amount of computational power she requires to immediately calculate insane data requests.

Some superheroes fared pretty well in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. The footprint for Jessica Jones, a superstrong antihero and private eye, measures 42,670 pounds, mostly for maintaining a fairly typical apartment in what might be Brooklyn, N.Y.

Swamp Thing, who takes carbon out of the atmosphere, has a footprint calculated at between −2.2 pounds and 0.18 pounds. Superman, however, really is super in this regard, with total carbon emissions of zero because his superpowers derive from absorbing energy from the Sun, according to Traer’s background documents, which reference the comics.

Up Next: Supervillains?

Linking science to popular culture “is a great way of getting people to engage with the science.”

With this project completed, Traer is considering looking at supervillains as a next step. “One of my favorites,” he said, “is Mr. Freeze, because refrigeration carries a pretty horrendous carbon footprint.”

Traer added that he wants to do his part to increase scientific literacy. “That’s the hill I’m willing to die on.” Linking science to popular culture “is a great way of getting people to engage with the science,” he added.

—Randy Showstack (@RandyShowstack), Staff Writer

Citation:

Showstack, R. (2017), Researchers explore carbon footprints of superheroes, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO088677. Published on 11 December 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.