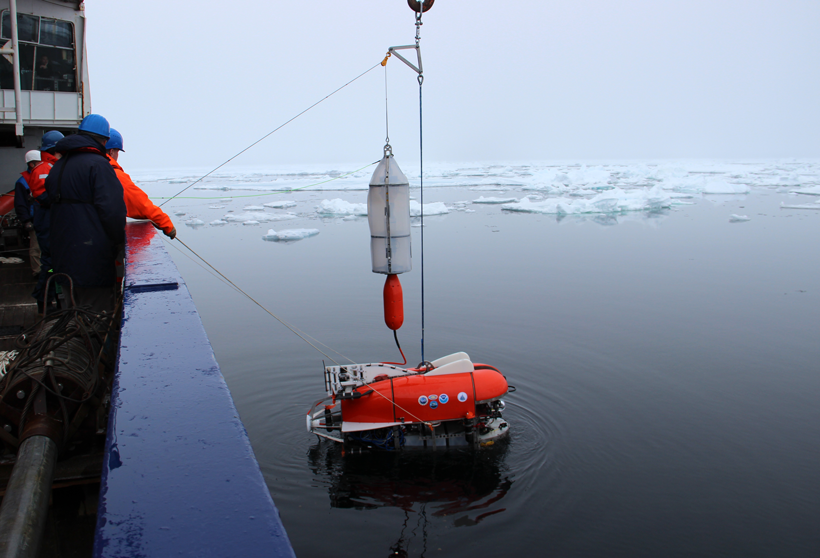

A new underwater vehicle has successfully demonstrated that it can explore physical and biological phenomena in undisturbed areas beneath sea ice. It has also shown that a thriving biological realm of algae and other creatures exists on and beneath at least some of the ice, according to scientists at a 16 December news briefing held during the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco, Calif. The Nereid Under Ice (NUI) vehicle, which completed its first series of trial under-ice dives during a July 2014 scientific expedition, is part of a series of technological advances that allows scientists to better understand the world’s oceans.

During those summer dives in the Arctic Ocean about 200 kilometers northeast of Greenland, NUI found unexpectedly high amounts of algae and other biological productivity under the ice that appear to support a diverse food web in the region, according to the scientists. “What might look on the surface like a barren wasteland may actually be a thriving biological community,” said Christopher German at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI). He is co–principal investigator for the design and construction of NUI and science lead for the NUI Arctic dives. The approximately $3 million vehicle was designed and built at WHOI, and it was tested during a scientific expedition aboard the Alfred Wegener Institute’s Polarstern research vessel.

“Whereas there are lot of autonomous vehicles that have been used to fly underneath a variety of ice-covered environments, including the glacial cavities, what NUI provides as a complementary capability is to use the real-time video and other sensor feedback that are coming back all the time to enable scientists to effectively explore in real time, to react to the unexpected,” German explained. During the series of dives, the vehicle operated at a distance away from Polarstern—and away from the influence of an ice-breaking research ship that by nature disrupts the ice—on both a thin fiber-optic tether and as a free-swimming autonomous vehicle.

“Why are we so fascinated with these under-ice situations?” asked Antje Boetius, Arctic expedition chief scientist with the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research. “One [reason] is it’s really a habitat for life and has always been a habitat for life.”

Boetius said that with climate change and the thinning and melting of sea ice, “the hardest answer of them all is what will it mean to us, what will it mean to life on Earth.”

Science and Engineering Working Together

“The greatest fun in science is, of course, when people tell you ‘you can’t do that’ or ‘you won’t manage’ or ‘this is not possible,’ and then you go and do it anyway,” she said. Boetius said that in 2009 when she was planning the expedition to explore the deep-sea floor and how climate changes under-ice habitat, the NUI did not yet exist. “I had big hopes, and I wrote it into the cruise proposal anyway that this robot would exist years later,” she said, noting that she was optimistic that the vehicle could be developed.

Michael Jakuba, lead project engineer for NUI at WHOI, said there was “a continual push-pull” in the interaction between engineers and scientists in developing the vehicle. “On the engineering side, we are trying to push the technology and trying to anticipate to some degree what the scientific needs might be and at the same time communicating what our capabilities are to the scientific community,” he said. “But in no way can we possibly imagine what people might want to do with such systems ahead of time entirely. So we build them to be flexible.”

German chimed in, “Historically, over my 20 years at this interface between science and engineering, the really coolest thing is as soon as you build something new, designed for one purpose, the first time you go out and use it, you find that you generate an entirely new scientific vocabulary and you develop a whole new range of programs you can now pursue scientifically where you could not have proposed that hypothesis previously because you weren’t even aware of a certain situation or a process.”

Part of a Series of Technological Advances

In an interview with Eos, WHOI president and director Susan Avery said, “The ability to have [NUI] look at the very complicated ecosystem and physical interactions with that ecosystem in a part of the world that is changing so rapidly is critically important. What happens in the Arctic is going to impact all of us, either whether you are thinking about it from an atmosphere point of view or from an ocean point of view.”

Avery also placed NUI within the larger context of ocean exploration. “I think of the ocean as the last frontier, and the need to explore our own planet is much more urgent in my mind than other planets, even though I know that the space program has been wonderful for the United States and for the world. But this is our planet. The ocean is a frontier, and there are major parts of the ocean that our technology is just now getting to the point where we can actually explore these frontiers, and one of the frontiers is that part under ice.”

She said that other ocean exploration frontiers include the deep trenches, mid-water column, and microbial world. “All of these frontier zones are reached right now because of technology advances,” Avery said.

—Randy Showstack, Staff Writer

Citation: Showstack, R. (2014), Robot explores under-ice habitats in the Arctic, Eos, 95, https://doi.org/10.1029/2014EO021181. Published on 24 December 2014.

Text © 2014. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.