Science, environment, and health journalists struggle to get information from governmental agencies for their stories and often need to go through public information offices to reach experts. That is a key finding from a 9 April report issued by the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

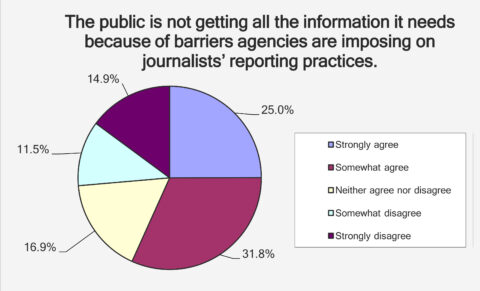

Most science journalists surveyed agreed that “the public is not getting all the information it needs because of barriers agencies are imposing on journalists’ reporting practices.”

The report, based on a new survey, found that science agencies “may be more open and less controlling than other types of government agencies surveyed in earlier studies.” However, a result from the new survey “shows that there are still extensive restraints on experts and journalists communicating with each other,” the report states.

A majority of science journalists surveyed, 56.8%, agreed with the statement that “the public is not getting all the information it needs because of barriers agencies are imposing on journalists’ reporting practices.” That figure is less than that in earlier SPJ surveys, in which 85% of journalists who report on federal agencies and 76.1% of education reporters agreed with that statement.

Media Access to Earth Science Agencies

At a briefing in Washington, D. C., to release the report, panelists acknowledged that some agencies involved with the Earth and space sciences have generally good media policies. The agencies they specifically cited include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and NASA. However, panelists said there is room for improvement at some other agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

According to the report, Mediated Access: Science Writers’ Perceptions of Public Information Officers’ Media Control Efforts, “the hazard of suppression of information and ideas is multifold. It includes muddling of understanding needed to solve problems, even among scientists themselves; manipulation of the public for various motivations; and the indefinite veiling of problems and malfeasance. Both the science and the journalism communities may want to consider issues the current situation presents in light of these findings.”

Other findings are that 46.1% of science journalists reported that they had been prevented from interviewing agency employees in a timely manner at least some of the time, which was higher than education journalists (32.6%) but lower than federal agency reporters (69%). Science journalists reported being more successful (32.2%) at getting interviews without involving an agency’s public information office (PIO) than other groups surveyed earlier, including education reporters at 21.3% and federal agency reporters at 15%. Also, 63.8% of science journalists reported having a positive working relationship with PIOs.

The survey, conducted by SPJ in January and February, elicited 254 responses from journalists covering science, environment, health, and medicine. The margin of error is ±5.7%. The report draws some conclusions from the findings, but it does not make recommendations, said report author Carolyn Carlson, a member of the SPJ Freedom of Information Committee. The committee is a watchdog of press freedoms across the United States.

Concern About Hampering the Information Flow

At the briefing, SPJ released a statement saying the new survey shows that “the restrictions specifically hamper the flow of scientific information to the public—which means they also hamper the movement of information to the rest of the community. The organization asked U.S. President Barack Obama “to end restrictions on reporters communicating with staff about the public’s business.”

Kathryn Foxhall, a member of the SPJ Freedom of Information Committee, said, “Over about 20 years, there has been a surge in agencies and other entities requiring reporters to always go through PIOs before speaking to employees. On an historical basis, the constraints are new and they are radical.” She added that “when reporters are required to go through PIOs to talk to anyone, the source people know they [are] under surveillance by the official structure and that changes everything.”

“The administration has entrenched this culture, these constraints that have been growing up over about three administrations.”

In an interview with Eos, Foxhall said that she and others were disappointed in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy’s guidance to federal executive departments and agencies on public communications that is included in a 17 December 2010 memorandum on scientific integrity. That memo states, in part, that “federal scientists may speak to the media and the public about scientific and technological matters based on their official work, with appropriate coordination with their immediate supervisor and their public affairs office.”

Foxhall told Eos that the language “was exactly the opposite of what we had been working for, and what we had told the administration needed to be done. To my knowledge, it was the first time in history that this policy of people being forbidden to speak to each other, except when they were under surveillance, had actually been put in written policy, by an administration.”

“The administration has entrenched this culture, these constraints that have been growing up over about three administrations,” she added. “And now, it is accepted around Washington that a reporter cannot speak to anyone in an agency without going through the public affairs office. That is message control.”

Transparency Efforts and the Obama Administration

Michael Halpern, program manager of the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Center for Science and Democracy, said that since President Obama took office, the administration has “talked about wanting to put a premium on transparency, with mixed results.”

Halpern said that although the administration has put a lot of effort into access to data, “there has been a lot less attention on those who can put meaning to that data and interpret it and put it in the proper context.”

He said that some agencies, including NOAA and USGS, have relatively open policies in working with the media and are setting the standards that other agencies should be able to follow. Halpern noted that media access has been “a sticking point” with EPA. He said that although the agency has made strides in other areas, “access to scientists is not one of those areas where there has been a lot of progress.”

“Scientists should be able to speak to the public and the press without having to ask for permission,” Halpern stated. He noted that scientists should be clear about when they are speaking as an agency representative and when they are speaking as an individual, to avoid confusion.

“The assumption should be openness unless there is a compelling reason” for not doing so, Halpern said. Further, he said that agencies should be looking at successful examples within government for best practices to replicate, so that as much information as possible can emerge “without compromising things like the scientific process or proprietary information or other things that rightly should be more private and more deliberative.”

Panelist Kate Sheppard, senior reporter and environment and energy editor at the Huffington Post, added, “Journalism benefits when reporters have access to experts, and society benefits because they have a better understanding of the issues when reporters have access to experts and not just the PIO.”

—Randy Showstack, Staff Writer

Citation: Showstack, R. (2015), Science journalists face government roadblocks, survey finds, Eos, 96, doi:10.1029/2015EO027981. Published on 10 April 2015.

Text © 2015. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.