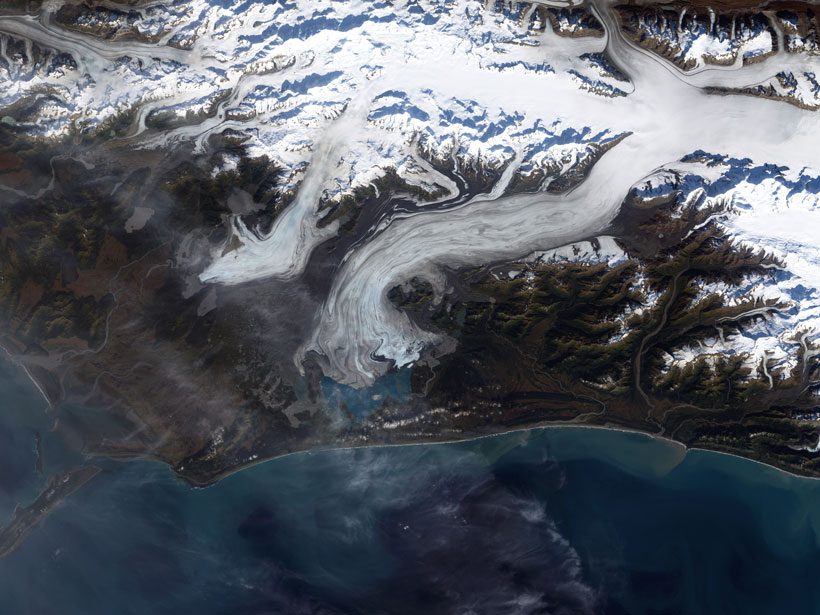

Far from being static features of the landscape, glaciers are dynamic rivers of ice, flowing and carving earth beneath them in a diverse range of rates. There are fast-flowing glaciers, slow or stagnant glaciers, and surging glaciers that periodically accelerate and slow down again.

Understanding glacier movement is essential for accurate modeling of future climate.

“Their physics are critical for our understanding sea level change,” says Zhongwen Zhan, a professor of geophysics at the California Institute of Technology, “because that is where you are draining the ice sheets into the oceans.”

It’s long been thought, Zhan notes, that liquid water at the base of glaciers might be acting as a lubricant, speeding glaciers up and along, but it is difficult to fully characterize what is taking place under many meters of ice. In a recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters, Zhan details the results of a new approach that offers a work-around.

Zhan’s insight was to make use of two seismological stations set up astride the surging Bering Glacier in Alaska. Zhan examined station data for a 12-year period, which included a surge that lasted from 2008 to 2010, measuring changes in the speed of background seismic waves as they passed through the glacier. He found that waves slowed down during the surge, indicating they were traveling though softer material—water rather than ice or rock.

“This sort of geological observation and seismological observation are coming together and showing the same phenomenon.”

Zhan thinks that the bottom 10 or 20 meters of a glacier crack during a surge, with those cracks running perpendicular to the direction of the glacier’s flow. Water, he says, rather than simply pooling at the base of the ice, fills these cracks. Zhan measured two types of seismic waves, Rayleigh and Love waves, to reach this conclusion.

“You have waves oscillating in the vertical direction, and another one in the horizontal direction, they are polarized,” he says. “Based on those differences in behavior of the polarization of the wave, we found that we need to have the cracks aligned perpendicular to the ice movement.”

Zhan’s research matches field observations of ridges of fine sediment left at the front of retreating surging glaciers, hinting at just these types of transverse cracks at the glacier base. “This sort of geological observation and seismological observation are coming together and showing the same phenomenon,” he says.

Zhan’s work is a step forward both in understanding surging glaciers and in furthering techniques for future studies, according Timothy Bartholomaus, a glaciologist and assistant professor in the University of Idaho’s Department of Geological Sciences.

“I think that it’s a very clever use of existing data and another really nice example of the ways by which people are applying techniques from seismology,” Bartholomaus says. “Over the last 5 or 10 years or so, there’s been a really major push by seismologists, oftentimes in collaboration with experts in other fields, to apply those same techniques to understand a whole range of other processes.”

An earlier study published in Geophysical Research Letters, for instance, used a network of 34 seismology stations in Antarctica to characterize high-frequency, wind-generated waves in ice shelves and correlated changes in the waves with a coming thaw.

Zhan would also like to extend his technique in future studies, perhaps adding additional seismological stations at different orientations across the glacier to better test his hypothesis.

“Our pair is aligned parallel to the cracks we are proposing. If we have a pair that’s perpendicular or 45° to the cracks, then we should see a change that’s very different,” he says. In the long term, with an array of sensors, a study could be like “the hospital people using X-ray or MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] to do tomography to show what the structure looks like and where something is changing.”

—Jon Kelvey (@JonKelvey), Science Writer

Citation:

Kelvey, J. (2019), Seismic clues to surging glaciers, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO124211. Published on 24 May 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.