Some 5% of signals recorded in the seismic record are caused by earthquakes. The rest is noise: Sensitive instruments pick up signals from ocean waves, storms, ice movement, hard-rock landslides, traffic, and even the occasional football game.

In examining this noise, scientists recently detected some strange signals emanating from the Gulf of Mexico. After a good bit of detective work, they determined the signals were coming from submarine landslides, about 10 per year, triggered by earthquakes hundreds to thousands of kilometers away. These findings have significant implications for the study of submarine slope failure processes and potential implications for paleoseismology, the oil and gas industry, and even coastal hazards assessments.

Seismic Noise

Seismologist Wenyuan Fan of Florida State University in Tallahassee was trying to understand the seismic noise across the United States, using USArray data, when he ran across “a lot of sources in the Gulf of Mexico and got very confused” because the Gulf region is not known for producing many earthquakes.

Fan and his colleagues went back through the data, combining USArray data with seismic data from many regional networks (including the Southern California Seismic Network and the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network) and then making sure the signals showed up on multiple arrays. They also compared the signals to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) database of known earthquakes.

All but 10 of the signals were preceded by earthquakes from magnitude 4.9 to 7.3, 1,000 kilometers or more away, suggesting that the landslides were triggered by remote earthquakes.

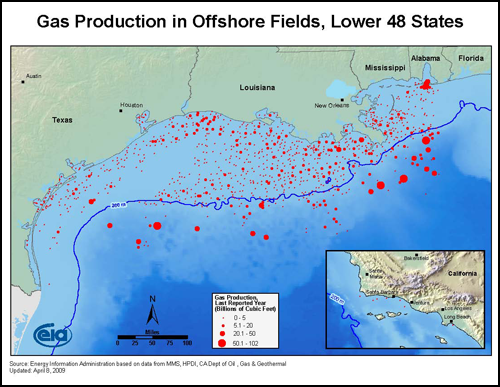

Fan and his colleagues, Jeff McGuire of the USGS and Peter Shearer of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, found 85 seismic events between 2008 and 2015 emanating in the Gulf of Mexico’s Western Planning Area, a region managed for development of oil, gas, and mineral resources by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. None of the 85 seismic sources showed up in the USGS earthquake database, suggesting the seismic events, some of which were as strong as a magnitude 3.5 earthquake, were not earthquakes.

The lack of faults and earthquakes in the region plus the abundance of these events “and the signatures of the waveforms led us to think they are likely to be submarine landslides,” Fan said. Furthermore, all but 10 of the sources were preceded by earthquakes from magnitude 4.9 to 7.3 emanating 1,000 kilometers or more away, and the occurrences of these events coinciding with the passing seismic waves from the remote earthquakes suggested that the landslides were triggered by remote earthquakes, the team reported in Geophysical Research Letters.

Remote Triggering

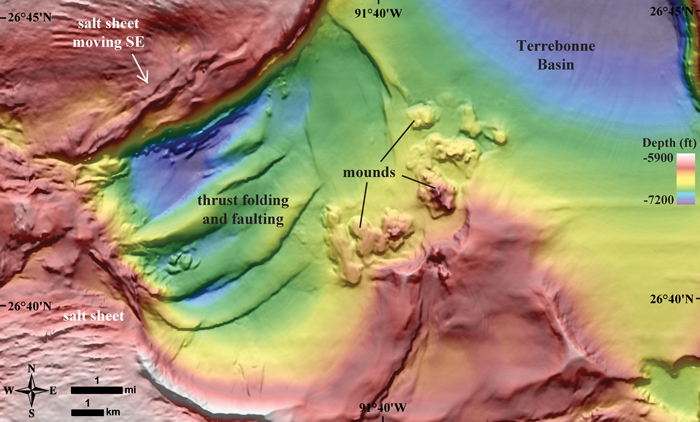

Not all geoscientists are convinced. For one thing, the Western Planning Area is riddled with faults throughout the salt diapirs that make up much of the subsurface, said Chris Goldfinger, a geologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis..

Though these don’t create traditional crustal earthquakes, they can shake. It is far more likely that the seismic signals Fan’s team observed came from quakes in the salt diapirs than from submarine landslides, Goldfinger said.

There has been no evidence of triggering of submarine landslides by remote earthquakes in the geologic record, he said, and submarine landslides are not known to produce seismic signals. “Submarine landslides, by nature—failing poorly consolidated materials in a low-gravitation environment—don’t make much noise, like marshmallows rolling down a gentle incline,” Goldfinger said. The submarine landslides would have to be enormous to create seismic signals, and that’s just not a likely scenario, he said.

However, Goldfinger added, the temporal links between seismic signals that Fan’s team found are intriguing. It’s quite possible, he noted, that the authors may have solved a resolution problem in the offshore Gulf: Quakes in the diapirs might have been occurring all along but hadn’t been seen by land-based seismometers until USArray.

Triggering of submarine landslides by local earthquakes is common and frequently used to identify past large earthquakes, such as those along the Cascadia Subduction Zone where Goldfinger works. If you shake the local layers of sediments on steep slopes hard enough, they will fail, producing turbidites, which can be dated to determine when the submarine landslide, and thus earthquake, occurred.

Triggering of one earthquake by another is also quite common. That’s because faults are often “ready to go,” Goldfinger said.

But landslides don’t fail by the same mechanism, Goldfinger explained. They are “different beasts.” If the ground was shaking strongly enough to trigger a landslide, in theory, it should trigger several or even a lot of landslides, not just one, as Fan and his team recorded, Goldfinger said.

Confirming Preconditioning

Michael Strasser, a marine geologist and sedimentologist at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, noted that recent research has indicated that steep slopes with high sediment rates (like the Gulf of Mexico) can be “preconditioned” to fail and may just need a little push.

A 2006 study in Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, for example, showed that Gulf of Mexico sediments are overpressured, Strasser said. If a seismic wave passes through overpressured sediments, it can cause them to fail. If you accept the preconditioning hypothesis, Strasser said, Fan’s “fascinating” results could make sense and “could indicate that such slopes are close to failure.” Of course, he said, he would really like to see some ground truthing.

Fan’s team did not confirm that any of the 85 submarine landslides they inferred through seismic data actually occurred because the team’s landslide location resolution is “too poor” to make a direct comparison to the high-resolution bathymetric data of the Gulf of Mexico, Fan said. Having an ocean bottom seismometer array in the Gulf would greatly improve the landslide location accuracy, he said.

Scientists could also survey the seafloor with “very, very good multibeam sonar or a submersible” before and after landslides, Strasser said, but it would be hard, given the size of the proposed landslides and the area to be surveyed plus current technology. One could also try drilling cores, said marine geologist Paul Johnson of the University of Washington. But engineers and scientists would need to know just where to drill.

Wide-Ranging Implications

The implications of Fan and his colleagues’ findings are wide-ranging. It’s pretty clear, Fan said, whether the seismic sources are submarine landslides or something else, that “it’s active out there” in the Gulf.

Although these landslides are small enough that they probably won’t change the tsunami hazard potential for Gulf Coast communities, they could change the picture for oil and gas operators in the Western Planning Area. Indeed, Goldfinger said, “if I were an oil guy reading this paper, I’d be concerned.”

The study also may have implications for paleoseismology because Fan and his colleagues “made a great case for remote triggering,” Johnson said. But correlating old submarine landslides with past earthquakes is done by correlating numerous sites “to assess the origins of event deposits and to filter out extraneous signals,” Goldfinger said. “You can’t compare just one earthquake and landslide.”

“It’s a beautifully testable hypothesis—great science.”

Strasser said it’s probably just going to take time before scientists have any idea how important this paper is: “I’m really looking forward to seeing this method applied elsewhere. If it’s fundamentally relevant, it should be detectable around the world.…It’s a beautifully testable hypothesis—great science.”

—Megan Sever (@MeganSever4), Science Writer

Citation:

Sever, M. (2020), Seismic noise reveals landslides in the Gulf of Mexico, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO144445. Published on 26 May 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.