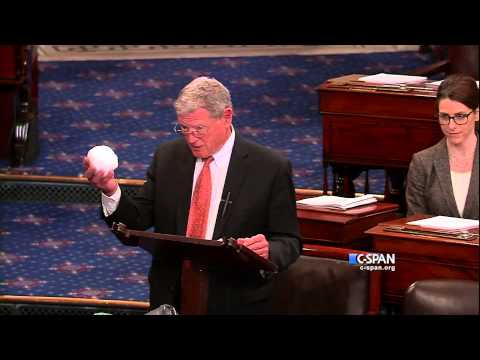

In February 2015, Oklahoma Senator Jim Inhofe presented a snowball to the U.S. Senate as proof that climate change isn’t real. His argument? That the current weather outside was just too cold, so global warming must be a hoax.

Jeremiah Bohr, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin in Oshkosh, told Eos that Inhofe’s stunt was “a powerful argument”—in a political sense.

“It’s interesting [to see] whether part of what shapes our perception of climate change is our experience of everyday weather and our memory of seasons in the recent past.”

Bohr recently published a paper in Climatic Change exploring the relationship between short-term climate anomalies, like an unseasonably cold February or an unseasonably warm March, and the political polarization surrounding the climate change conversation.

“It’s interesting [to see] whether part of what shapes our perception of climate change is our experience of everyday weather and our memory of seasons in the recent past,” Bohr said.

Even though climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that Earth is warming and that humans drive this warming by releasing greenhouse gases, as soon as a cooler day blows through or “you get that snowball,” those who don’t believe in climate change—people who are more likely to be Republicans or conservative leaning—will “double down” on those beliefs, Bohr said. Similarly, Bohr found that warmer- or cooler-than-average days will reinforce a belief in climate change among Democrats.

Watch the snowball incident here:

Surveys of Opinion

To find out how short-term climate anomalies affected the polarization of climate change opinions, Bohr looked at CBS/New York Times surveys of American adults for four periods over 2 years: February and March 2013 and February and May 2014.

The surveys asked respondents whether they thought global warming is an environmental problem causing serious impact now, will have an impact in the future, or will have no impact at all. It also asked respondents to identify whether they believe that climate change is real, caused by humans, or caused by natural variation. Bohr then compared these results with national monthly temperature averages compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration over those 2 years and assumed that those who answered the survey questions were in their states of residence at the time.

Bohr found that when temperatures were 3° or more higher or lower than a 5-year average, a higher percentage of Democrats provided answers supporting the existence of climate change, whereas a higher percentage of Republicans provided answers denying the existence or danger of climate change. Both ends of the political spectrum committed more to their respective opinions, Bohr said.

For Democratic or liberal-leaning respondents, this trend meant that slightly cooler or warmer temperatures convinced them even more that climate change was real. For Republican or conservative-leaning respondents, the opposite was true: slightly cooler or warmer temperatures convinced them even more that climate change was either not real or not a problem.

Media Matters

Bohr wonders whether the “entrenched” political polarization of news media could contribute to these responses.

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that 47% of “consistent conservatives” mainly get their news from Fox News, and 88% of consistent conservatives trust Fox News over other news outlets like NPR, the New York Times, MSNBC, BBC, and others. Fox News has been criticized for its climate change coverage—or lack thereof. A Media Matters study from 2013 found that when covering a United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, Fox News cast doubt on the science behind climate change 75% of the time over a 2-month period.

Polarization of the media means that “we don’t really have a common space where we can all agree that there [is an] objective set of studies and facts.”

Meanwhile, BBC, NPR, and the New York Times were the most trusted by liberal respondents, and those outlets haven’t faced as much criticism for their climate change–related coverage (although recently New York Times has come under fire for hiring a columnist who some people say holds contrarian views on climate change that fly in the face of the scientific evidence for it).

This polarization of the media means that “we don’t really have a common space where we can all agree that there [is an] objective set of studies and facts,” Bohr said. “I just don’t think, as long as our media networks are as polarized as they are, that we’re going to see this polarization going away.”

“Political ideology is the strongest predictor of your opinion on climate change in the [United Sates],” said Peter Howe, a geographer who studies the perception of climate change at Utah State University in Logan and wasn’t involved with the new paper.

Although Howe finds the new study intriguing, he said he’d like to see more research into how particular climate events—and their effects on the public’s opinion about climate change—might affect conversations surrounding mitigation efforts.

—JoAnna Wendel (@JoAnnaScience), Staff Writer

Citation:

Wendel, J. (2017), Unseasonable weather entrenches climate opinions, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO074473. Published on 24 May 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.