A quick Google search of “micrometeorites” brings up such titles as “How to Collect Micrometeorites in Your Backyard” and “How to Find Micrometeorites in Your Home,” boasting of how simple it is to find space dust among mundane neighborhood debris. But if you asked experts, they might have said that finding micrometeorites in urban areas is a myth.

Until now.

“I have walked for days, weeks, months, and years in London, Paris, Rio, Los Angeles, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and sampled dust in order to see if it was possible” to find micrometeorites in urban environments.

For the better part of a decade, Jon Larsen, a Norwegian independent scientist who studies micrometeorites and runs Project Stardust, collected hundreds of kilograms of urban dust and debris, sorted through the mess, and found micrometeorites.

“I have walked for days, weeks, months, and years in London, Paris, Rio, Los Angeles, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and sampled dust in order to see if it was possible” to find micrometeorites in urban environments, he said. And last year, he succeeded.

Larsen presented his findings this month at the Meteoritical Society’s meeting in Berlin, Germany.

Hunting for Space Dust

Micrometeorites are tiny particles of space dust. They come from meteoroids, asteroids, or even larger bodies like Mars or the Moon, and scientists estimate that between 5 and 300 metric tons rain to Earth every day. But when Larsen spoke with other scientists about the possibility of finding micrometeorites in urban environments, they didn’t think it was possible to find them among human-made contaminants.

“There are, on the Internet, numerous educational activities that encourage people to collect debris from rain gutters and roofs,” said Dolores Hill, a research specialist at the University of Arizona, who has studied meteorites since the 1980s but wasn’t involved in the current research. “[We’re] told that anything spherical and magnetic is a micrometeorite.”

Larsen wasn’t deterred. Since 2009, he has analyzed hundreds of kilograms of urban dust, picked out more than 40,000 individual particles under a microscope, and further analyzed nearly 1000 micrometeorite candidates under an electron microscope, looking for telltale extraterrestrial signs.

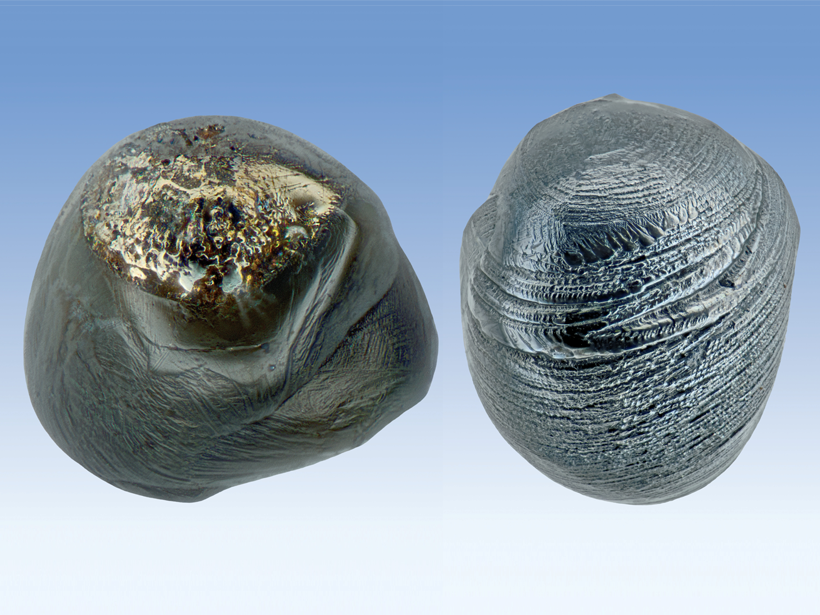

Micrometeorites range from 50 to 100 micrometers across—for perspective, a human hair is 40–50 micrometers wide. They come in all shapes, derived from their violent entrance into the Earth’s atmosphere—the friction from which can melt them completely.

Micrometeorites contain iron, silicates, or minerals like olivine or orthoclase. These minerals can all be found in Earth rocks, but micrometeorites tend to be ultramafic, meaning that they have more magnesium and iron, said Susan Taylor, a research scientist at the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research Laboratory in Hanover, N.H., who was not involved in the research. On the Earth, it’s rare to find ultramafic rocks on the surface, Taylor added.

Further, meteoritic iron contains a higher abundance of nickel than terrestrial iron, so if an iron-containing particle doesn’t have nickel in it, Taylor wouldn’t consider it to be extraterrestrial.

It’s certainly possible for anyone to find extraterrestrial particles in their own neighborhoods, but it would be a monumental task for any layperson or even amateur astronomer to take on.

Other telltale qualities of a micrometeorite include a black, shiny luster, presumably gained when the micrometeorite partially melted as it hurtled through Earth’s atmosphere. But micrometeorites don’t have to be darkly colored—some lose their iron and completely melt into clear, glassy spheres made of silicon, magnesium, and oxygen.

After 6 years of combing through debris, Larsen identified his first micrometeorite in February 2015 with the help of astronomer Matthew Genge at the Imperial College of London. Once he knew what he was looking for, Larsen scoured roofs and gutters in Norway, recruited volunteers and construction workers to send him debris, and ended up with 300 more kilograms of refuse. In that load, Larsen found more than 500 micrometeorites.

“I did not think it would be possible to find [urban micrometeorites] in one lifetime,” Larsen said.

And since he’s refined his methods, “several batches of 20 grams of magnetic particles collected on urban roofs have resulted in 20 new micrometeorites each,” he continued.

Chemical Confirmation

Hill is excited about the research. Urban micrometeorites are extremely hard to find, she said, because human-made materials easily pass as micrometeorites. These contaminants can come in the form of welding debris, ash, or other industrial by-products.

That’s why researchers travel to the ends of the Earth to find micrometeorites. Scientists find these particles in Antarctica, in Greenland, and in deep-sea sediment—but not in the middle of a city because of all the possible contaminants. A visual identification isn’t enough, Hill continued, which is why Larsen and Genge’s research is promising.

“They have actually conducted chemical analysis,” she said. “And petrographic analysis as well. Both of those things, to me, are required to identify whether a particle is truly a micrometeorite or not.”

Labor of Love

Although the findings are an impressive feat, hunting for micrometeorites in urban areas may not be the most efficient way to find them, Taylor said. She herself has found hundreds to thousands of micrometeorites just sampling the bottom of a South Pole well. Finding even 500 extraterrestrial particles in 300 kilograms of debris isn’t promising for scientific intrigue, she said.

Although Larsen, Genge, and Taylor agree that it’s certainly possible for anyone to find extraterrestrial particles in their own neighborhoods, it would be a monumental task for any layperson or even amateur astronomer to take on.

“It’s really a great labor of love,” Taylor said.

—JoAnna Wendel, Staff Writer

Citation:

Wendel, J. (2016), Urban micrometeorites no longer a myth, Eos, 97, https://doi.org/10.1029/2016EO057895. Published on 24 August 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.