Preparation for the research cruise in the northern Gulf of Alaska in May began in an unusual way for chief scientist Russ Hopcroft: 2 weeks of self-quarantine at home with his family.

Since the novel coronavirus put ocean-going research at a standstill, many scientists wonder how they’ll ever sail again. Research cruises have tight quarters, take scientists sometimes weeks away from land, and bring people from all over the world into the same cramped location. In March, the organizational body for U.S. universities, the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS), halted all research cruises until 1 July.

Oceanographers have returned to the same track for 22 years.

That is, except for Hopcroft’s cruise. The weeklong jaunt on the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s (UAF) ship the R/V Sikuliaq was initially planned for 2 weeks in April. Scientists intended to measure the extent of the Gulf of Alaska’s vibrant spring plankton blooms. The annual measurements inform Alaska’s fishery management quotas for next year.

Oceanographers have returned to the same track, called the Seward Line, for 22 years, and missing out this year would have not only starved management agencies of data but caused greater uncertainty in that data.

Alaska has had the lowest number of recorded cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, of any state, according to NPR. Just this week, reported cases ticked up by a few or less per day statewide. Alaskans are well suited for social distancing and staying away from stores, said UAF professor Hopcroft. “This is Alaska. We’re used to having several weeks’ supplies on hand at any one time.”

“It’s Just Kind of Weird”

Being out on the water with so few people is strange, said Hopcroft. The scientists each have their own berthing and bathroom, a luxury for research ships that are usually packed to the brim with scientists, graduate students, technicians, and crew. Every other seat in the ship’s dining area is blocked off too. “It’s just kind of weird to be out here and have the ship so empty.”

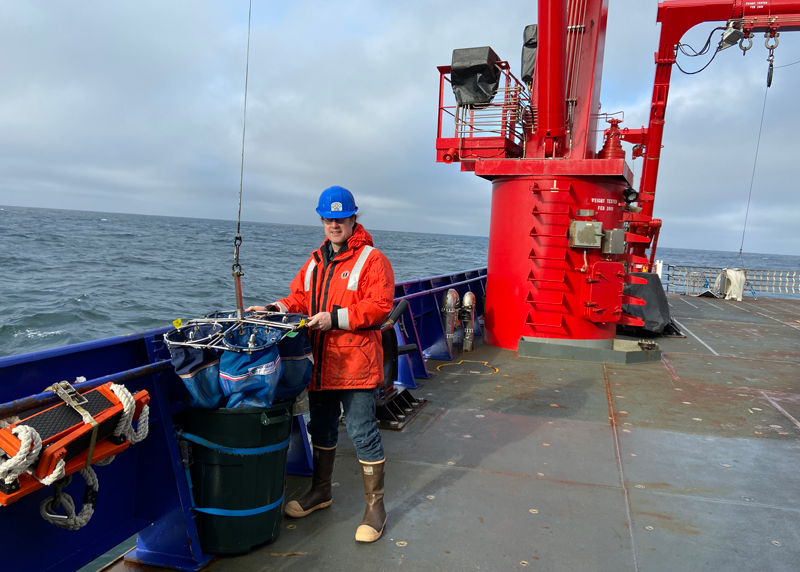

Cruise organizers compressed the ship time in half, stayed closer to shore, and reduced the 24-scientist team to just three researchers, each from a unique discipline: biological, chemical, and physical oceanography. The skeleton crew prepared with their colleagues over Zoom, taking instructions on how to collect samples for one another.

Everyone on board takes their temperature and oxygen levels several times a day at a station on the ship, writing the values down on a log sheet. The three scientists self-quarantined for 2 weeks before the cruise and drove the 10 hours from Fairbanks to Seward in personal vehicles with no interaction with the outside world. The crew quarantined for 3 weeks and took COVID-19 tests a few days beforehand.

“This will probably be one of the few data sets being taken this spring up here in the gulf.”

The physical oceanographer on the team, UAF associate professor Seth Danielson, said that he didn’t view the cruise as a risk for his personal health because of the extensive precautions taken. If anything, he said, “we’re feeling really lucky to be out right now” given that so many expeditions have been canceled. The cruise organizers coordinated with the U.S. Coast Guard, UNOLS, the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and health mandates by Alaska’s governor.

UAF associate professor and chemical oceanographer Ana Aguilar-Islas said that being on board has distracted her from the news. “I kind of have forgotten that there’s a pandemic out there. That’s really a welcome change. I don’t find myself checking the [COVID-19 case counts] as much.” Aguilar-Islas said she and her colleagues are working 14–16 hours per day.

Hopcroft said that it was crucial to get these data. “This year, with there being so few other measurements being taken by other colleagues, this will probably be one of the few data sets being taken this spring up here in the gulf.”

Still, future cruise planners will face some tough decisions, Danielson said. With limited people allowed on board, how will graduate students receive field training? Having rapid COVID-19 tests with a high degree of accuracy would help reduce any “room for doubt” of possible infections, Hopcroft said.

“The UAF team demonstrated that seagoing science can be conducted during this time of the pandemic,” Craig Lee, UNOLS chair said. “That said, each cruise presents a unique set of challenges and must thus be assessed individually for risk and mitigation.”

For now, Lee said, cruises that save instruments and data or continue long time series are the most urgent.

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), Staff Writer

Citation:

Duncombe, J. (2020), What it’s like to social distance at sea, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO144098. Published on 12 May 2020.

Text © 2020. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.