Editors’ Vox is a blog from AGU’s Publications Department.

Being an experienced researcher can come with a lot of heavy professional responsibilities, such as leading grant proposals, managing research teams or labs, supervising doctoral students and postdoctoral scientists, serving on committees, mentoring younger colleagues … the list goes on. This may also be a time filled with greater personal responsibilities beyond the job. Why add to the workload by taking on a book project? In the third installment of career-focused articles, three scientists who wrote or edited books as experienced researchers reflect on their motivations and how their networks paved the way for—and grew during—the publishing process.

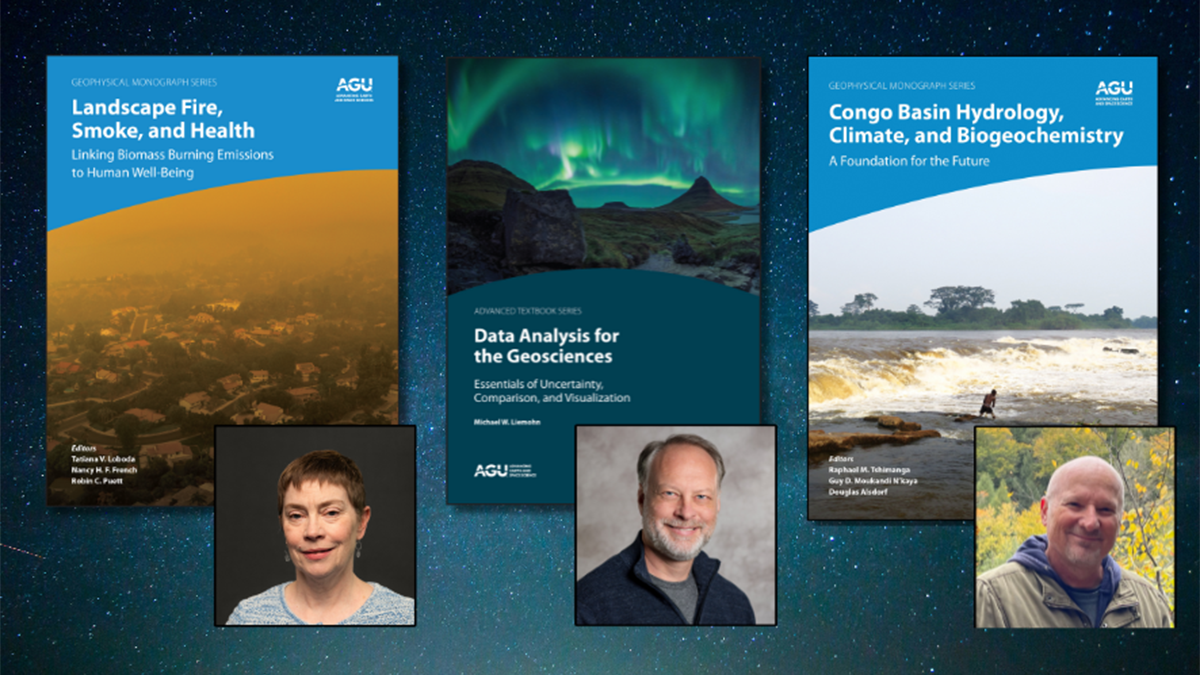

Douglas Alsdorf co-edited Congo Basin Hydrology, Climate, and Biogeochemistry: A Foundation for the Future, which discusses new scientific discoveries in the Congo Basin and is published in both English and French. Nancy French co-edited Landscape Fire, Smoke, and Health: Linking Biomass Burning Emissions to Human Well-Being, which presents a foundational knowledge base for interdisciplinary teams to interact more effectively in addressing the impacts of air pollution. Michael Liemohn authored Data Analysis for the Geosciences: Essentials of Uncertainty, Comparison, and Visualization, a textbook on scientific data analysis and hypothesis testing in the Earth, ocean, atmospheric, space, and planetary sciences. We asked these scientists why they decided to write or edit a book, what impacts they saw as a result, and what advice they would impart to prospective authors and editors.

Why did you decide to write or edit a book? Why at that point in your career?

ML: I was assigned to develop a new undergraduate class on data-model comparison techniques. I realized that the best textbooks for it were either quite advanced or rather old. One book I love included the line, “if the student has access to a computer…” in one of the homework questions. I also was not finding a book with the content set that I wanted to cover in the class. So, I developed my own course content set and note pack, which provided the foundation for the chapters of the book.

DA: Our 2022 book was a result of a 2018 AGU Chapman Conference in Washington, DC, that I was involved in organizing. About 100 researchers, including 25 from sub-Saharan Africa, attended the conference, and together we decided that an edited book in the AGU Geophysical Monograph Series would become a launching point for the next decade of research in the Congo Basin.

The motivation for the book was not to advance my career, but because the topic was important to get out there.

NF: The motivation for the book was not to advance my career, but because the topic was important to get out there. The book looks at how science is trying to better inform how to manage smoke from wildland fires. The work was important because people in fire, smoke modeling, and health sciences do not work together often, and there were some real misconceptions about how others do the research and how detailed the topics can be.

What were some benefits of completing a book as an experienced researcher?

NF: Once you have been working in a field for a while you want to see how your deep expertise can benefit more than just the community of researchers that you know or know of. Reaching into other disciplines allows you to understand how your work can have broader impact. And, you are ready to know more about other, adjacent topics, rather than a deeper view of what you know already. I think these feelings grow more true as you move to later stages of a career.

I think that I would have greatly struggled with this breadth of content if I had tried to write this particular book 10 years earlier.

ML: I was developing my data-model comparison techniques course and textbook for all students in my department, so I wanted to include examples across that diverse list of disciplines—Earth, atmosphere, space, and planetary sciences. Luckily, over the years I had taught a number of classes spanning these topics. Additionally, I had attended quite a few presentations across these fields, not only at seminars on campus but also at the annual AGU meeting. I felt comfortable including examples and assignments from all these topics. Also, I knew colleagues in these fields, and I called on them for advice when I got stuck. I think that I would have greatly struggled with this breadth of content if I had tried to write this particular book 10 years earlier.

What impact do you hope your book will have?

The next great discoveries will happen in the Congo Basin and our monograph motivates researchers toward those exciting opportunities.

DA: There are ten times fewer peer-reviewed papers on the Congo Basin compared to the Amazon Basin. Our monograph changes that! We have brought new attention to the Congo Basin, demonstrating to the global community of Earth scientists that there is a large, vibrant group of researchers working daily in the Congo Basin. The next great discoveries will happen in the Congo Basin and our monograph motivates researchers toward those exciting opportunities.

ML: I hope that the book has two major impacts. The first expected benefit is to the students that use it with a course on data-model comparison methods. I want it to be a useful resource regardless of their future career direction. The second impact I wish for is on Earth and space scientist researchers; I hope that our conversations about data-model comparisons are ratcheted up to a higher level, allowing us to more thoughtfully conduct such assessments and therefore maximize scientific progress.

What advice would you give to experienced researchers who are considering pursuing a book project?

NF: Here are a few thoughts: One: Choose co-authors, editors, and contributors that you can count on. Don’t try to “mend fences” with people you have not been able to connect with. That said, if you do admire a specific person or know their point of view is valuable, this is the time to overcome any barriers to your relationship. Two: Give people assignments, and they will better understand your point of view. Three: Listen to your book production people. They are all skilled professionals who know more about this than you do. They can be great allies in getting it done!

DA: Do it! Because we publish papers, our thinking tends to focus on the one topic of a particular paper. A book, however, broadens our thinking so that we more fully understand the larger field of work. Each part of that bigger space has important advances as well as unknowns that beg for answers. A book author who can see each one of these past solutions and future challenges becomes a community resource who provides insights and directions for new research.

—Douglas Alsdorf ([email protected], ![]() 0000-0001-7858-1448), The Ohio State University, USA; Nancy French ([email protected],

0000-0001-7858-1448), The Ohio State University, USA; Nancy French ([email protected], ![]() 0000-0002-2389-3003), Michigan Tech Research Institution, USA; and Michael Liemohn ([email protected],

0000-0002-2389-3003), Michigan Tech Research Institution, USA; and Michael Liemohn ([email protected], ![]() 0000-0002-7039-2631), University of Michigan, USA

0000-0002-7039-2631), University of Michigan, USA

This post is the third in a set of three. Learn about leading a book project as an early-career or mid-career researcher.