Long before the neon lights and artificial fountains of the Las Vegas Strip, people were attracted to the Las Vegas Valley by its artesian springs. Las Vegas means “the meadows,” after all, and for thousands of years, this valley tucked between arid mountain ranges was a startlingly green oasis in the midst of the Mojave Desert.

In 1962, after decades of groundwater pumping, the Las Vegas Springs ran dry, and today 90% of the water that flows through the valley’s faucets comes from the Colorado River by way of Lake Mead.

In the grip of an already decadelong drought and with the climate projected to get even hotter and drier, the valley’s growing population of 2.7 million residents and 42 million annual visitors is expected to get even thirstier, making a return of the Las Vegas meadows highly unlikely.

Groundwater Everywhere

Las Vegas Valley is a 1,600-square-kilometer basin bordered on all sides by mountains, containing the second-largest metropolitan city in the desert Southwest (behind Phoenix). Underlying the sprawling concrete and casinos is a surface layer of white rock known as the Las Vegas Formation.

For decades, scientists thought this white layer was evidence of a valley-wide ancient lake bed. “Some old maps still show pluvial Lake Las Vegas, but there’s no hydrographic closure to enclose a lake,” said Kathleen Springer, a research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Pasadena, Calif.

“The Las Vegas Valley has the best and most complete wetlands groundwater discharge sequence found anywhere in the world.”

The white rocks are actually groundwater discharge deposits that preserve a 573,000-year history of springwater-fed marshes, meadows, grasslands, and streams that expanded and contracted through time. “The Las Vegas Valley has the best and most complete wetlands groundwater discharge sequence found anywhere in the world,” Springer said.

The valley’s once copious groundwater originates in the Spring, Sheep, and Las Vegas mountain ranges, where moisture falls as rain and snow. The runoff makes its way into the valley, percolating through the thick layers of sediment that have accumulated on the valley floor and flowing along faults into two large aquifer systems. The 30- to 90-meter-thick near-surface reservoir is a shallow aquifer, underlain by a layer of clay that separates it from the deeper 305-meter-thick principal aquifer.

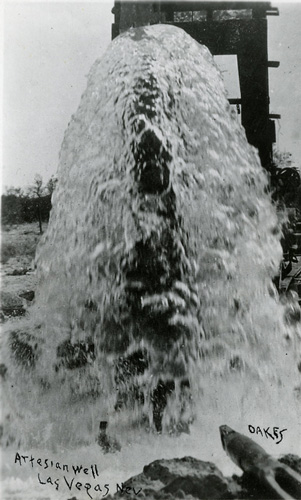

Groundwater moves readily through the valley’s loose gravels and sands, occasionally encountering less permeable clay and silt layers, where it builds up fluid pressure and sometimes finds its way to the surface via fault systems, emerging at pressurized artesian wells that gush water across the landscape.

Groundwater, Grasslands, and Giant Ground Sloths

In the past, springs and a wetter climate fed a lush, valley-wide wetland ecosystem that sustained large populations of mammoths, camels, bison, and giant ground sloths.

These herbivores were prey to animals like dire wolves and saber-toothed cats, said Steve Rowland, a paleontologist at the Las Vegas Natural History Museum. “During the Wisconsin Glaciation, the Las Vegas Valley was a very different environment than it is today. It was a lot greener, and the climate was a lot wetter.”

Fossils found in the Las Vegas Formation from the period between 100,000 and 12,500 years ago represent one of the most significant late Pleistocene vertebrate faunal records in the American Southwest, Rowland said. Much of the record is preserved: After the economic downturn of 2008, tracts of fossil-rich land slated for development were instead protected to form the Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument. Abundant fossil deposits have been found throughout the valley, and mammoth tusks are regularly uncovered during construction projects.

People likely began migrating through the Las Vegas Valley at least 13,000 years ago and likely encountered the soon-to-be-extinct megafauna. Clear evidence of early human activities is scant, however; the hunter–gatherers were seasonal migrants and left few artifacts in their wake. “Whether…humans were major players in the extinction event remains an open question,” Rowland said.

Clear evidence for permanent human habitation around the valley’s springs and creeks dates back at least 5,000 years and includes campfire hearths, pit houses, spearpoints, pottery, and petroglyphs. The ancient Patayan, as well as the modern Northern and Southern Paiute, Washoe, and Shoshone people, trace their ancestry to the ancient people who were first drawn to the Las Vegas Valley by the miracle of water in the desert.

From the Meadows to the Strip

The original Las Vegas Springs were named in 1829 by a Spanish expedition pioneering a route for what would become the Old Spanish Trail between Santa Fe, N.M., and Los Angeles. The spot where the water came to the surface is known as the birthplace of Las Vegas and can be visited at Springs Preserve, about 6.5 kilometers northwest of the Las Vegas Strip.

At the time they were named, the artesian wells at Las Vegas Springs were producing 5,000 acre-feet (6.2 million cubic meters) of water per year, enough to support around 20,000 people. (An acre-foot of water is the volume that would fill 1 acre of surface area to a depth of 1 foot, about 1,233 cubic meters.) The springs soon became a major waypoint for travelers on the Old Spanish Trail as well as for Mormon missionaries.

The first successful well in the Las Vegas Valley was drilled in 1907, and in March 1911 the city of Las Vegas was officially incorporated with about 800 residents. By 1912, more than 100 wells had been drilled. “Many of these wells were uncapped, and water was just spewing across the landscape. There was a lot of waste,” said Tracie Jackson, a hydrologist with the USGS Nevada Water Science Center in Henderson.

By 1930, more than 5,000 people lived in Las Vegas. The Great Depression brought a large influx of people to the valley as well as construction of the Hoover Dam (then called the Boulder Dam) between 1931 and 1936. The Hoover Dam impounds the Colorado River to create Lake Mead.

By 1950, the valley’s population had increased to 40,000 people. Thousands of wells drew more than 35,000 acre-feet (43.2 million cubic meters) of groundwater per year, exceeding the aquifer’s natural annual recharge rate of 25,000 acre-feet (31 million cubic meters). In 1962, Las Vegas Springs ran dry.

Overpumping of groundwater persisted. By the 1980s, more than 2 meters of subsidence forced entire neighborhoods to relocate. To combat this issue, the city began pumping water out of Lake Mead and into the underground aquifers. “Las Vegas was one of the first cities to run a managed aquifer recharge program,” said David Kreamer, a hydrogeologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Between 1988 and 2011, the city pumped tens of thousands of acre-feet of water underground each year, slowing the rate of subsidence, but the Las Vegas Springs never started flowing again. For the springs to restart, approximately 2 million acre-feet (2.5 billion cubic meters) of water would need to be injected into the aquifer, Jackson said. Even at that rate, “the spring flows would be small trickles of water. For Las Vegas Springs to flow again at predevelopment rates, much more would need to be injected beyond any new pumping.”

After a long period of drought significantly lowered water levels in the Colorado River and Lake Mead, the managed aquifer recharge program was suspended in 2011. However, the city continues to extract upward of 70,000 acre-feet (86 million cubic meters) of groundwater per year, nearly 3 times the natural recharge rate.

Today the Las Vegas Springs have run dry, but many more springs still flow throughout the state. The nearest place to see a modern analogue of the original springs is at Corn Creek, a U.S. National Wildlife Refuge northwest of Las Vegas at the base of the Spring Mountains.

Desert Treasure

I’ve never bet a dollar in Las Vegas, but I’ve been to Nevada many times seeking two of my favorite desert treasures: rock art and hot springs. Most rock art panels are well documented, and some are even marked on Google Maps. But it’s more fun to find them the old-fashioned way: by looking for rocks that would make good community message boards. The best method is to start at a water source and then survey the landscape for rocky outcrops or ridges where people might have sat in the shade and watched other people and animals visiting the springs.

Nevada has more than 1,200 documented prehistoric rock art sites. The sites closest to Las Vegas can be found at Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area and at Valley of Fire State Park. The majority of rock art in Nevada is typically carved or pecked into the rock, with painted-on pictographs less common. Petroglyphs are notoriously hard to date and even harder to interpret, but they provide one of the most visible records of Nevada’s early inhabitants.

Nevada also boasts more than 300 naturally sourced hot springs, the most of any U.S. state. Hot springs form when geothermally heated groundwater makes its way to the surface. One of my favorite desert discoveries was a heart-shaped hot tub at a Bureau of Land Management site in central Nevada, complete with a valve to shut off the 39°C water between soaks.

The natural hot springs closest to Las Vegas emerge in a slot canyon above the Colorado River, just downstream from Hoover Dam.

Making Every Drop Count

Las Vegas is famous for being a place of excess, but over the past 20 years the metropolitan area has made tremendous strides in boosting water conservation practices. Since the early 2000s, southern Nevada’s population has nearly doubled, but per capita water usage has dropped by 38% and the overall consumption of Colorado River water is down 25%, according to the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA).

“We recycle more than 99% of our wastewater from indoor water use,” said Bronson Mack, outreach coordinator for SNWA. That means that most of the water that runs down household and commercial drains in southern Nevada gets returned to Lake Mead after treatment via the Las Vegas Wash, an urban river that also drains storm water out of the city.

The recycled water helps to bolster southern Nevada’s water budget. “For every gallon of water we return to Lake Mead, we can take another gallon out,” Mack said. Pooled together, the cities represented by SNWA—including Las Vegas, North Las Vegas, Henderson, Boulder City, and Laughlin—are allocated 300,000 acre-feet (370 million cubic meters) of water from Lake Mead annually.

“Our 300,000 acre-foot allocation is for consumptive use,” Mack said. “That’s water we can take out of the river and not return. In a given year, we end up diverting in excess of 400,000 acre-feet [493 million cubic meters] from the river, but we return about 200,000 [247 million cubic meters] back to Lake Mead. We have made considerable investment in water conservation programs and have realized outstanding water savings, but we’re not done yet.” Last year, the city’s per capita water use was around 424 liters per day. “In true Vegas style, we will continue to double down on our efforts,” Mack said.

Green Past, Arid Future

Much of the West, including southern Nevada, is experiencing long-term drought. “Last year, we went 240 days with no measurable rainfall in Las Vegas,” Kreamer said. “From late April 2020 to late April 2021, we got 1.22 inches [3 centimeters] of rain. Normally, we get a little over 4 inches [10 centimeters] of rain a year.”

The Las Vegas Valley is no stranger to dry periods. “These desert wetlands ecosystems have waxed and waned over geologic time,” Springer said. “We’ve documented megadrought over and over throughout the record.” But the modern megadrought is an entirely new animal, driven by anthropogenic warming and exacerbated by millions of people drawing from finite desert water resources.

Watch as irrigated vegetation (red) and impervious surfaces (gray) expand outward from Las Vegas, while Lake Mead (right) shrinks. Credit: NASA

Even the lifeline of the Colorado River, fed by snowfall in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Wyoming, is running drier. “The Colorado River has been overallocated for decades, and it’s only going to get worse as the climate gets hotter and drier,” Kreamer said.

“The SNWA recognizes that climate change is here and now and the drought we are experiencing is a manifestation of climate change, and that it’s going to require all of us on the Colorado River to use less.”

“The SNWA recognizes that climate change is here and now and the drought we are experiencing is a manifestation of climate change, and that it’s going to require all of us on the Colorado River to use less,” Mack said.

Water budgets for southern Nevada currently are planned for 50-year horizons, and some models aren’t that optimistic about the water supply. “Some of our more extreme projections show us exhausting our resources in the 2030s or 2040s,” said Mack. “We…have enough water banked at current usage rates to last 8 years to help us bridge any future gaps.”

Even on geologic timescales, the long-term prospects for water and large grazing animals returning to the Mojave Desert are bleak. “It’s hard to predict the future of climate change, but everything shows that the next 100 years is going to be hotter and drier,” Jackson said.

“The long-term future of Las Vegas will depend on human activity,” Rowland said. “It’s pretty clear that we’ve disrupted the normal pattern of glacial cycles and we shouldn’t expect a return to green Las Vegas on human timescales. Beyond that, there’s really no way to predict what will happen, but it’s hard to imagine anything but desert here in the future.”

—Mary Caperton Morton (@theblondecoyote), Science Writer

Living in Geologic Time is a series of personal accounts that highlight the past, present, and future of famous landmarks on geologic timescales.

Citation:

Morton, M. C. (2021), Is green Las Vegas gone forever?, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO158878. Published on 28 May 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.