In 1872, the British Challenger expedition sailed around the globe on a voyage to study and sample the world’s oceans. The expedition is thought to be the first scientific oceanographic cruise.

Of the 243 people on board the Challenger, not one was a woman. Women weren’t allowed on ships, research or otherwise.

But nearly a century before the Challenger, a woman by the name of Jeanne Baret sailed around the world on a scientific expedition of her own. Baret disguised herself as a male assistant on a 1766 voyage led by the French admiral and explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville to document plants and ecosystems in distant countries. Baret is the first woman on record to have circumnavigated the globe.

Science, especially science on ships, has a long history of excluding women. And since the beginning, women like Baret have undermined and pushed back against the rules. Women finally secured the ability to participate in scientific cruises in the United States in 1959 and now lead expeditions, research institutions, and federal agencies.

Contemporary oceanographers face less obvious problems: a culture of scientific research founded in exclusion and still grappling with explicit and implicit bias, unsafe work environments, and a lack of institutional support.

Robin Nelson, a biological anthropologist at Santa Clara University who studies issues of harassment and assault, said that discrimination threatens the meritocratic nature of science itself.

“We frame science as this idea that folks with the best ideas, folks who are willing to work hard, are those who are going to succeed,” Nelson told Eos. But without safeguards protecting vulnerable scientists, she said, “those folks who could be supertalented, wonderful scientists get pushed out of our fields.”

Peter Girguis, an oceanographer at Harvard University, agrees. “In the absence of gender equality, we’re doing mediocre science,” Girguis said.

For the 2019 World Oceans Day theme of “Gender and the Ocean,” the United Nations writes that the empowerment of women and girls is “still needed” in all aspects of ocean-related sectors, including marine scientific research.

The theme begs the question: What barriers do modern women face in the ocean sciences, particularly those working in the field? And how can recent upgrades in technology, policy, and cultural awareness counteract these issues?

Potholes to Progress

The rate of women’s professional involvement in oceanography is sometimes referred to as a “leaky pipeline.” Initially, the flow of young women into the profession is strong but dwindles as they choose to leave for numerous reasons.

Women and men enroll in undergraduate and graduate programs in oceanography in equal numbers, according to a 2014 study in Oceanography. (Numbers for gender-nonconforming individuals were not reported.) But only 15% of full or senior faculty positions across 26 U.S. institutions were held by women in 2014. The authors found that women “continue to drop out as they progress along the tenure track,” which they note is similar to other disciplines in science.

LuAnne Thompson, a physical oceanography professor at the University of Washington, said that the field has been trying to fix the leaky pipeline for decades.

“People recognized it was a problem, but they thought of quick fixes,” Thompson said. Initiatives pushed the hiring of more female faculty in the 1990s, she said, but gave little thought to the cultural change needed to support them.

The result left women navigating a landscape of potholes throughout their careers. One woman deliberated over whether to mention her family in a job interview. Another noticed how she was spoken over at meetings. And still others struggled with the aftermath of harassment and assault.

“I can count other African American women in oceanography on one or two hands. That really needs to change.”

Women belonging to marginalized groups, including people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people of differing abilities, face heightened obstacles in the sciences. Marine geologist and Esri Chief Scientist Dawn Wright said that although the number of women may be increasing in the field, the number of women of color is not.

“I can count other African American women in oceanography on one or two hands,” Wright told Eos. “That really needs to change.”

To learn more about the challenges faced by female oceanographers in their everyday lives, Eos spoke with working oceanographers across disciplines. From outright bias to lackluster university support, from subtle discrimination to sexual assault, female scientists described a suite of challenges that build up over time, becoming what one researcher called a “death by a thousand cuts.”

But just as female scientists struggled against cultural and structural barriers in the past, modern women have found ways to overcome and cope with inequality. Their actions, both interpersonal and policy facing, are part of the movement to rewrite an exclusive culture’s rules, just as Jeanne Baret did centuries before.

“Isn’t That a Man’s Job?”

When Asha De Vos left her home in Sri Lanka to pursue an education in Scotland, she said, “most people were convinced I would never come home.”

De Vos had dreamed of a life as a marine biologist from a young age. But when she told others of her aspiration, she said, “most people had never heard of [it].”

After completing her doctoral and post-doctoral research, De Vos returned home, where she studies populations of blue whales in the northern Indian Ocean, focusing on conservation and reducing instances of ship strikes. But early in her career, government officials in Sri Lanka overlooked her work, according to De Vos, often favoring the advice of men less qualified than she was.

“They were invited to meetings and listened to, despite the fact that what they had to say was nothing concrete,” De Vos told Eos.

De Vos frequently chafed against the male-driven society of Sri Lanka, coping with outright discrimination and bias.

“They’ll continuously say things like, ‘Oh, but isn’t that a man’s job?’” said De Vos.

After she appeared on an international television program speaking about her research, De Vos faced sharp criticism. When the video showed up as a clip on YouTube, De Vos called the video comments “horrific.”

“I genuinely cried for about 4 hours reading them,” she recalled.

De Vos found most of the criticism fixed on her gender, not her credibility.

“I was at that point, and still am today, the only person with this kind of knowledge in this entire country,” she said. Still, critics “weren’t valuing me on what my capacity [was], but they were basically attacking me on my physical appearance.”

“As a Human, I’m Not Addressed”

Seagoing oceanographer Ivona Cetinic remembered hearing flack early in her career, like being told that because she was a woman, she “shouldn’t be doing certain things.”

As she advanced in her career, the comments stopped, and in their place, Cetinic faced a new type of barrier: a lack of institutional support for women starting families.

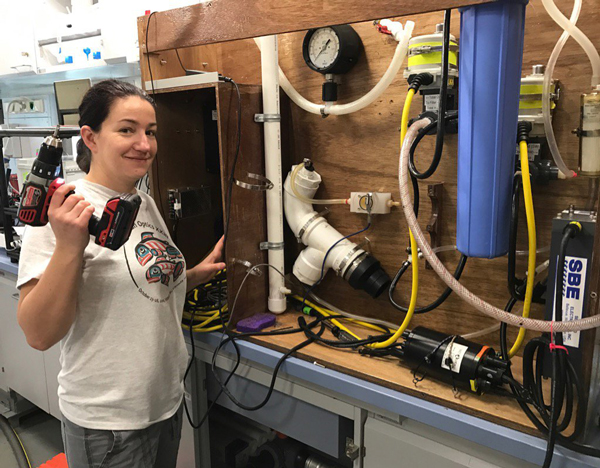

Cetinic typically sailed on one or two long cruises per year as well as frequent daylong trips, retrieving new field data of phytoplankton populations to inform satellite images. In 2013, she planned to attend a cruise shortly after the birth of her first child. Since she had a nursing newborn, she didn’t want to throw away her milk while at sea.

Cetinic checked the website of the organizational body in charge of university vessels, the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS), for recommended procedures for lactation at sea. She discovered that the information didn’t exist. This realization came on the heels of another experience, months before, in which she couldn’t find clear guidelines regarding attending a cruise while pregnant.

“As a human, I’m not addressed.”

“There was, once again, no clear documentation that I could follow,” Cetinic said.

Cetinic turned to Twitter and connected with women facing similar challenges, who recommended she bring a freezer on the ship to store her milk. Thanks to her network, she knew what to do on her upcoming cruise, but when it came to university policy, there was a lack of support for her needs.

“As a human, I’m not addressed,” she said.

“End of My Patience”

Women in oceanography also cope with instances of sexual harassment and assault.

Oceanographer Julia O’Hern, manager at the nonprofit Marine Mammal Center in Moss Landing, Calif., published an account in the Washington Post in 2015 describing her experiences facing discrimination, harassment, and assault while working on research ships as crew and as a scientist for her postdoctoral research at Texas A&M.

O’Hern recounted a list of unwanted behaviors by coworkers, who made comments about her body and suggested that she wasn’t hirable because of her gender. One colleague’s behavior took a turn for the worse, O’Hern wrote, when he entered her room at night and groped her.

O’Hern reported several instances of misconduct through numerous channels, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and her university. O’Hern told Eos that after 3 years of investigations, the institutions decided that there was “insufficient evidence or jurisdiction.”

After speaking out, O’Hern said she was not able to finish her postdoctoral project and lost several important professional relationships. Although she knew that going public about her experience would come with repercussions, O’Hern said that she couldn’t stay silent any longer.

“I was just at the end of my patience level with certain behaviors,” O’Hern said. After finishing her Ph.D. and working hard on her shifts, it was just too insulting, she said, to “‘suck it up’ and ignore it.”

She hoped that the article could open a conversation about not just assault but the culture of discrimination that women endure.

“It’s hard when we feel like we can only talk about these things after it becomes a criminal case,” she said. “If we were to nip it in the bud a little earlier, we wouldn’t have to get to this horrible level.”

Not Alone

Not all women experience discrimination in science: Some have fulfilling careers and choose to stay or leave the field on their own terms. But the experiences of De Vos, Cetinic, and O’Hern mirror those of many others in oceanography, including experiences documented in published literature. The discrimination described by De Vos echoes an ethnography published in 2018 describing the culture of the Ocean Observatories Initiative, where project scientists chronicled instances of explicit and implicit bias. Several recent quantitative studies have also illuminated subtle biases in hiring, manuscript reviewing, and letters of recommendation in the geosciences.

The dearth of support for new parents, recounted by Cetinic, parallels complaints of more than 200 autobiographical sketches of female ocean scientists outlined in a 2014 special issue in Oceanography. Nearly every sketch mentioned issues with work-life balance, and the special issue’s editor, Ellen Kappel, called it the “biggest challenge” facing women in science today.

Instances of sexual harassment and assault, like those experienced by O’Hern, are frighteningly common across the sciences. Although no study on the prevalence of harassment and assault exists for oceanography, a 2014 PLoS ONE survey of over 600 scientists from fieldwork-intensive disciplines found that nearly two thirds of the survey respondents had personally experienced sexual harassment and close to a quarter had experienced sexual assault while conducting fieldwork. The study did not have a random sample and therefore cannot represent the prevalence of harassment and assault, but the study’s authors write that the findings reveal a “substantial degree” of problematic behavior in the sciences.

New Policies, Technology, and Cultural Conversations Offer Hope

Can recent shifts in policy, technology, and cultural norms make science more equitable? And how are women, with actions both big and small, rewriting the culture of oceanography to bolster all scientists?

Shortly after O’Hern published her article in the Washington Post, staffers from the office of Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) reached out.

An effort was underway in the legislature to clarify NOAA’s policy for reporting harassment and assault on vessels, and they wanted O’Hern’s input. She worked with legislators to introduce policy to ease victims’ experiences reporting to NOAA.

The new policy added several safeguards to support victims of harassment and assault. A new 24-hour hotline eases reporting from ships, letting victims report without the use of the ship’s often public and limited phone or radio channels. Under the new policy, anyone working on a NOAA vessel—from employees to contractors to university affiliates—will have the power to report, and be reprimanded, through the agency. This patches a loophole that O’Hern faced while reporting issues as a contracted deckhand and university scientist.

Scientific societies and organizations are revising scientific policies to better protect scientists. The Oceanography Society (TOS) listed harassment and assault as scientific misconduct in late 2018 and created an ethics committee to investigate reported cases of misconduct. AGU instituted a similar policy in 2017 and recently created free legal consultations for students, postdoctoral researchers, and untenured faculty.

Calls for better resources for women with children helped spur the creation of a UNOLS ad hoc committee to address the working conditions on the organization’s 21 research vessels. The group sent out recommended policies to ship operators for pregnant women and nursing mothers in 2016, which cochair Mark Brzezinski said many operators adopted.

Telepresence on ships gives pregnant mothers and others a new way to participate in research cruises. Katy Croff Bell, a deep-sea explorer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), said that this technology has been used on research vessels for many years, like NOAA’s R/V Okeanos Explorer and the Ocean Exploration Trust’s E/V Nautilus.

“Now we’re in a place where the broader academic community is talking about diversity and culture and implicit bias and privilege.”

Finally, shifts in awareness offer hope. Nelson, who publishes papers on harassment and assault in science, said that initially, her colleagues brushed off her work. But after the #metoo movement, “that’s not a discussion anymore,” said Nelson.

Thompson said that conversations about diversity have evolved since she was hired in the 1990s.

“Now we’re in a place where the broader academic community is talking about diversity and culture and implicit bias and privilege,” said Thompson. The conversations go “beyond just women” to include ethnic and socioeconomic diversity, she added. Programs like Minorities Striving and Pursuing Higher Degrees focus on professional development for underrepresented minorities in the geosciences.

Peter Girguis said that men can support and champion women in science as well. He encourages men to be aware of their biases and hear what women have to say. “Being inclusive and supportive of women is about listening and understanding individual needs,” he said.

Solace

For De Vos, she said that she took refuge in building strong partnerships and in the support from her parents. She started to see those who lashed out at her as jealous of her ability and took it as a sign that she was “doing something right,” she said.

These changes, said De Vos, “allowed me to just start to build self-belief that told me that, you know what? It doesn’t matter in the end,” De Vos said. “The ocean needs me more than what these people have to say.”

These women, and many others, take solace in the joys of their community, their families, and the ever-present pull of ocean exploration.

After years of working to engage the government in marine conservation issues in Sri Lanka, she said, a government minister finally reached out and asked for her advice.

Cetinic agreed that a supportive community and mentorship can be transformative. “It’s very hard to take a step into the unknown if there’s nobody down there to catch you if you fall,” she said.

These women, and many others, take solace in the joys of their community, their families, and the ever-present pull of ocean exploration.

O’Hern still works on ships, coordinating efforts to rescue and rehabilitate injured marine mammals. As she wrote in the Washington Post, “Why should I or other women pursue careers in which our colleagues devalue us in this manner? Because discrimination will never compare to the joy of sailing out toward the clouds, salt spray soaking the air.”

—Jenessa Duncombe (@jrdscience), News Writing and Production Fellow

7 June 2019: This article has been updated to better reflect scientific research in Sri Lanka.

Citation:

Duncombe, J. (2019), Women in oceanography still navigate rough seas, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO125909. Published on 06 June 2019.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.

Text © 2019. AGU. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.