How do you explain solar physics to a 10-year-old? Very carefully.

I’ve been a professional writer for almost 2 decades, contributing to outlets like Science, Astronomy, and Eos, but by far the most difficult and specialized work I’ve done has been writing for young readers.

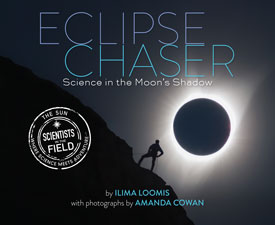

Yet that’s the challenge I took on when I agreed to write Eclipse Chaser, the latest installment in Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s award-winning series for young readers, Scientists in the Field, and the first book in the series to cover solar physics.

Eclipse Chaser tells the story of University of Hawai‘i solar physicist Shadia Habbal as she leads an expedition to Oregon to observe the 2017 North American total solar eclipse. Shadia has been studying eclipses since the 1990s, and her work has led to groundbreaking discoveries about the ionization of chemical elements at different temperatures in the solar corona—important insights into the coronal heating problem.

I’d previously written about Shadia, and although I found her work fascinating, I sometimes struggled to follow the details of her research myself or to describe it in language even other adults could understand. So although I knew that her work was important and she’d be a wonderful subject for a book, I also knew it would be difficult to share this complex science with kids.

Difficult—but worth it. As I’d gotten to know Shadia, I’d come to find her curiosity about the Sun infectious. What causes solar flares? How does the solar wind work? Why is the Sun’s atmosphere so much hotter than its surface? It intrigued me to think that this star could be so tantalizingly near, wield so much influence over our planet and our solar system, and yet still hold so many mysteries. I knew kids would be intrigued too.

.

.

Fortunately, I had some experience writing for young people and had worked with the wonderful editor Janet Raloff. Janet taught me that you don’t have to dumb science down to make it interesting and accessible to kids, but you do have to be thoughtful in the way you write about it. You might need to give more background information than you would if you were writing for an audience of scientists. Choose simple, concrete words over scientific jargon. Break up long-winded explanations into shorter sentences and paragraphs. Use metaphors and analogies to help kids visualize abstract ideas. And most important, tell a good story.

Fortunately, a total solar eclipse is a naturally compelling tale. The event itself is dramatic and spectacular, whereas the journey to observe one is a daunting, high-stakes scientific quest—offering a big payoff when things go right and a lot of opportunities for things to go wrong. Shadia and her team were full of stories about braving deserts, snowstorms, mosquito swarms, unhelpful border agents, and even polar bears to observe eclipses, only to have months or even years of work and preparation ruined by a passing cloud or last-minute dust storm.

I knew that if I could find a way to explain the science, the story would tell itself.

.

I met with Shadia and a few other members of her team in Honolulu several times before the eclipse to talk about her plans and make sure I understood the scientific questions she would be investigating on this expedition. In August of 2017, I flew to Portland, Ore., to meet up with award-winning photographer Amanda Cowan and join Shadia and her team in the field, on a private ranch in the central part of the state.

.

The team was incredibly generous in allowing us to pitch our tent alongside them, in inviting us to join them for a meal, and especially in making time to talk with us and letting us observe and photograph them as they got ready for the big event. We got to spend time not only with Shadia but also with many of her collaborators, including engineer Judd Johnson, physicist Adalbert Ding, mathematicians Miloslav Druckmüller and Pavel Štarha, solar physicist Enrico Landi, and many others.

On the morning of the eclipse, a haze of smoke from distant wildfires was cause for worry (and, I thought privately, dramatic tension!), but the skies soon cleared, and we were treated to a perfect, glorious totality. Shadia got the data she wanted, and I had an incredible story to tell—one with a happy ending.

—Ilima Loomis ([email protected]; @iloomis), Science Writer

Citation:

Loomis, I. (2020), Big science, small package: The joys of writing science for kids, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO138997. Published on 24 January 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.