Source: Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans

The Mozambique Channel, between Mozambique and Madagascar, is home to some of the most turbulent waters in the ocean. Swirling at a rate of more than 1 meter per second, currents in the channel can form structures known as anticyclonic rings that spread up to 350 kilometers across—about the width of Missouri—and extend 2,000 meters below the surface.

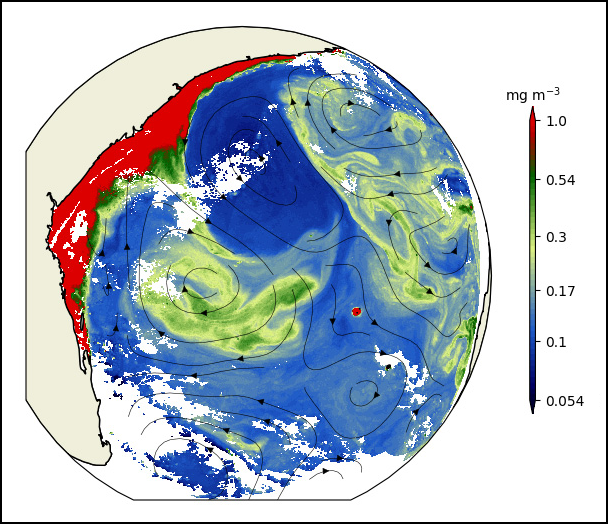

The currents carry nutrients and marine life such as shrimp larvae, the basis of a major industry in Mozambique. Information about the movements of shrimp larvae and their food is crucial for managing fisheries. Yet currents in the Mozambique Channel remain poorly understood.

Penven et al. characterized currents in the channel as part of a study called RESILIENCE (Fronts, Eddies, and Marine Life in the Western Indian Ocean). In 2022, the research team set off aboard a vessel towing a Moving Vessel Profiler, which measured water conductivity, temperature, and turbidity in the region with unprecedented spatial resolution. Meanwhile, an instrument on the ship’s hull, called the RDI Ocean Surveyor Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler, measured water velocity.

Specifically, the researchers traversed a prominent type of current in the Mozambique Channel known as an eddy-ring dipole. In an eddy-ring dipole, an anticyclonic ring—in which water swirls counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere—pairs with a cyclonic eddy—in which water swirls clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. Using the profiling instruments, the team took high-resolution measurements of several cross sections of the current down to a depth of 300 meters.

The fierce central current formed by the eddy-ring dipole whisked nutrients and sea life away from the continental shelf and the Mozambican coast at speeds of up to 1.3 meters per second, the researchers found. They also found that conditions vary significantly between the current’s two parts. In the cyclonic eddy, patches of either high or low salinity exist and photosynthetic life is abundant. In the anticyclonic ring, on the other hand, conditions are homogeneous and photosynthetic life is largely absent. The study is among the first to characterize these complex currents, and it provides a basis for future research on this turbulent region, the researchers say. (Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JC021913, 2025)

—Saima May Sidik (@saimamay.bsky.social), Science Writer