The Waitepuru Stream flows from its headwaters in the Mokaingarara Hills, down to the Rangitaiki Plains, and through the tiny community of Matatā as it makes its way to New Zealand’s wide Bay of Plenty.

For generations, local Māori have conceptualized the stream as a taniwha (water monster) in the form of a lizard. The river’s headwaters are the taniwha’s head, the main channel is its sinuous body, tributaries form its legs, and where the river leaves the hills and flows onto the plain, that’s its flicking tail.

And flick it does. Large flood events periodically cause the lower part of the channel to overrun its banks and change course, moving back and forth across the plain over centuries.

“Through time it behaves just like the flicking tail of a lizard,” said Dan Hikuroa, an Earth systems scientist and senior lecturer in Māori studies at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

The taniwha story, however, is so much more than myth, Hikuroa said. It’s a pūrākau—a traditional form of Māori narrative codified in story form. (Matatā elders gave Hikuroa permission to share it.)

The lizard shape describes the geomorphology of the stream, and the presence of the taniwha conveys a warning: “Not only does it tell you what to expect—that the tail will flick from side to side—but because it’s codifying it as a taniwha, it effectively becomes a disaster risk reduction strategy at the same time. It’s the evidence, and it’s the policy,” Hikuroa explained.

In 2005, flash floods sent debris flows roaring down the Waitepuru and a neighboring stream. The Waitepuru shifted course by a few meters. And while dozens of buildings were rendered uninhabitable, none of Matatā’s three marae—Māori communal meeting houses—were affected. “To me, that’s not by chance,” Hikuroa said. “You don’t build your critical infrastructure where the tail flicks.”

For Hikuroa, who is Māori, it’s a prime example of the ways that pūrākau and other forms of Mātauranga Māori (comprising Māori knowledge, culture, values, and world view) can inform and complement geomorphology.

“Indigenous Knowledge is just as accurate and reliable and rigorous and precise as the knowledge that geomorphologists produce. It’s just codified differently,” Hikuroa said.

Two Braided Streams

Mātauranga Māori is increasingly being woven with mainstream science in New Zealand. As part of efforts to give effect to the Treaty of Waitangi (signed in 1840 between Māori and the British Crown) the country’s interdisciplinary National Science Challenges are required to engage with the Vision Mātauranga policy, which encourages the integration of science and Mātauranga Māori.

Recent studies have outlined how this weaving might be done in the fields of conservation translocations, oceanography, and marine management. In other colonized countries, too, there is increasing recognition of the benefits—and the ethical considerations—that emerge when scientists and Indigenous Peoples work together to produce new knowledge.

Though few studies have been done so far, Indigenous Knowledges are especially applicable to geomorphology, said Clare Wilkinson, a doctoral student at New Zealand’s University of Canterbury and lead author of a new paper in Earth Surface Dynamics that proposes frameworks for integrating Indigenous Knowledges with Earth science.

“Geomorphology…is all about what’s going on at the surface and how different parts of the landscape interact with each other. That’s so much of what Indigenous Knowledge is—their cumulative relationships with landscapes throughout generations,” Wilkinson said.

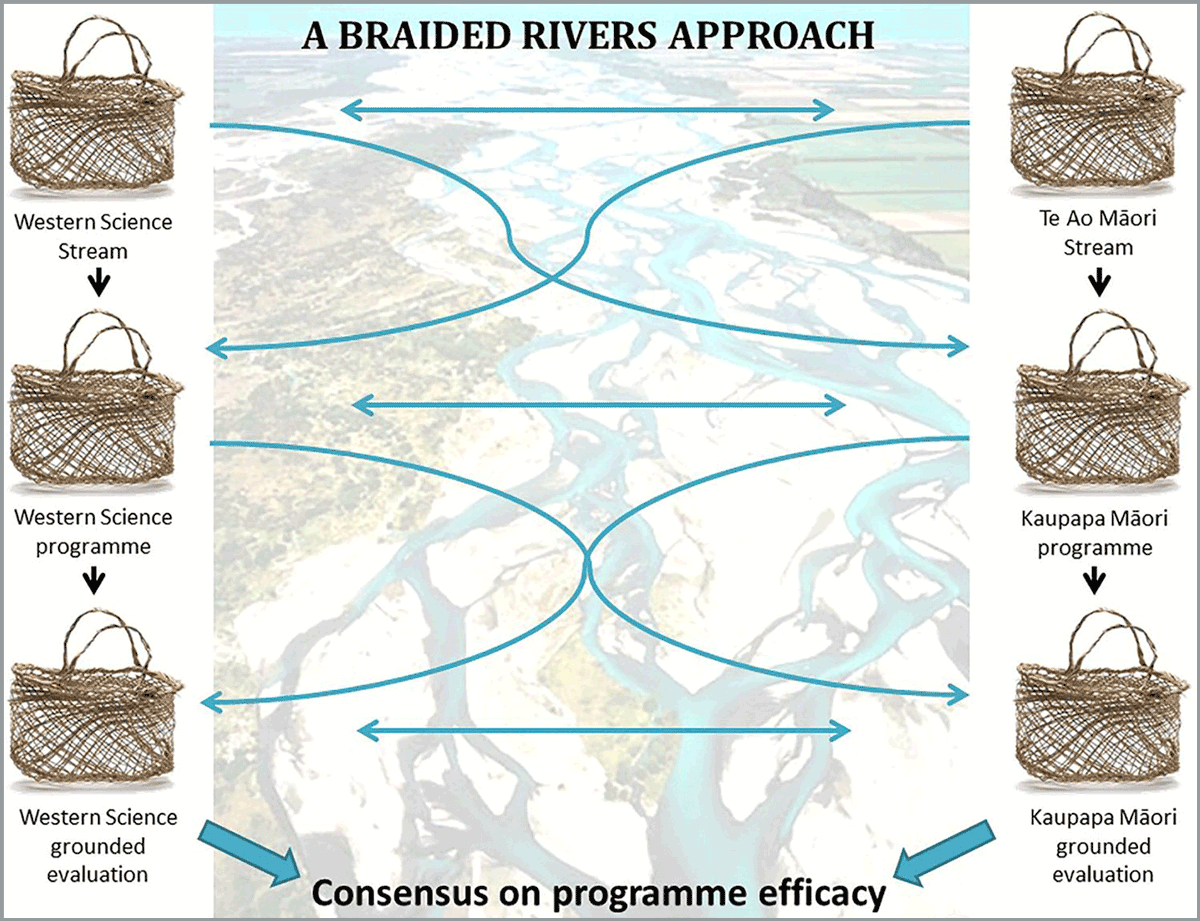

In her own research into how river systems in the Kaikōura area responded to landslides triggered by the massive 2016 earthquake, Wilkinson is using a framework developed by one of her supervisors, Angus Macfarlane, called He Awa Whiria (braided rivers approach) to weave together Western science and Mātauranga Māori.

The framework is inspired by the South Island’s iconic braided rivers, which consist of a network of interwoven channels separated by temporary islands.

Indigenous Knowledges and science represent separate streams that periodically meet, inform, and guide each other, Wilkinson said—with studies’ conclusions drawn from both channels.

“Ultimately, those streams meet at the river mouth before they go out to sea,” she said.

Rights for Rivers

Some of Hikuroa’s research has focused on the Whanganui River, the longest navigable waterway in New Zealand, which flows from the snow-tipped volcanoes of the North Island’s central plateau to the Tasman Sea. In world-leading legislation in 2017, the river was granted the rights and responsibilities of legal personhood and recognized as Te Awa Tupua (literally, a river with ancestral power.)

The law declared the Whanganui River “a living and indivisible whole” comprising the whole of the waterway “from the mountains to the sea, incorporating its tributaries and all its physical and metaphysical elements.”

Hikuroa found that passage inspirational. “Some people in other places might say that’s greedy or dreaming about a utopia,” he said. “Well, that’s law here. Physical, metaphysical, indivisible, whole.”

In a 2018 paper, Hikuroa and some colleagues began to think through what role geomorphology could play in identifying, articulating, and protecting the rights of the Whanganui and what geomorphologists could learn from Māori ways of knowing and relating to rivers.

Drawing the knowledge streams together, Hikuroa and his colleagues suggested seven geomorphic rights for the river, including the rights to be healthy, to be diverse, and to evolve and, most importantly, the right to flowing water—the right to be a river.

Taking those rights seriously might imply changes to policy and management that give up some control and allow rivers more space, Hikuroa said.

“When a river floods, it’s a nuisance to us, but it’s a nuisance because we forgot it was a river in the first place. We put our bridges across it. We built our houses on the flood plains. And we’re starting to realize now that in fact, the cheaper option and the best option is to just say, ‘Okay, river, you be you.’ When a river floods, it’s just a river being a river.”

More Than “Nice Stories”

“There was very much a paternal attitude at the time, a sort of ‘well, they are nice stories, but we know best, modern science is the way to go.’”

Indigenous Knowledges are also an integral component of the New Zealand Palaeotsunami Database. When James Goff started researching tsunamis in the 1990s, he was amazed to find that Māori oral histories about disastrous waves were not taken seriously by scientists. “There was very much a paternal attitude at the time, a sort of ‘well, they are nice stories, but we know best, modern science is the way to go.’”

As a result, Goff suspected, scientists underestimated the tsunami threat.

Goff, now an honorary professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia, and Darren King, a Māori researcher from New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Science, began working collaboratively with different Māori groups to assemble pūrākau about large waves and cross-reference them with geological and archaeological information.

The paleotsunami database, which is freely available for anyone to consult, draws data from both scientific and Indigenous sources. Cultural records make up more than 14% of the total.

“They can extend our knowledge of what past tsunamis have done to humans back hundreds of years from the earliest historical records of the 1820s,” Goff said. “Without this knowledge we would live in blissful ignorance of what will happen in the future.”

Open Heart, Open Mind

Despite the progress, recent studies have shown that Māori scientists are severely underrepresented in New Zealand’s universities and Crown Research Institutes and their careers are more likely to be negatively affected by COVID-19.

Scientists can learn a lot from Indigenous ways of knowing, Hikuroa said—and there are things they might need to unlearn, too. Chief among these might be that the scientific way of knowing and explaining the landscape is the only way. “Sometimes people forget that they have a dominant view because it becomes invisible.”

Researchers hoping to work with Indigenous Peoples will have to learn new skills in cross-cultural communication and build reciprocal, respectful relationships, Wilkinson said. Researchers may also need to accept that some knowledge will not be shared with them.

“Some of the knowledge of Indigenous groups is extremely sacred, and there are times when it just won’t be appropriate to weave the two together,” she said.

However, Hikuroa said, the benefits for geoscience are considerable.

“If you do things right and with an open heart and open mind…your understanding of how the world operates and how geomorphology operates will be much greater because you’re able to draw from a much richer knowledge base. When we bring together these two bodies of knowledge, we can imagine things that neither could deliver in isolation.”

—Kate Evans (@kate_g_evans), Science Writer

Citation:

Evans, K. (2020), The river’s lizard tail: Braiding Indigenous Knowledges with geomorphology, Eos, 101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EO148717. Published on 14 September 2020.

Text © 2020. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.