Source: GeoHealth

This article also may be read in Arabic.

Fossil fuel combustion produces greenhouse gases that heat the planet, but it also emits air pollutants that harm human health. Fine particulate matter and ozone, for example, have been linked to fatal lung and heart issues. And a recent study published in GeoHealth adds to the growing body of research that shows that when countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, the associated improvements in air quality could save countless lives.

Reducing emissions in these countries from power plants alone could reduce that death toll by nearly 300,000 lives.

Researchers used computer simulations to quantify the deaths associated with power plant emissions globally. Then, they modeled how those numbers might change if G20 countries, which include the world’s biggest economies, kept on pace to reach their net zero emissions goals.

The team concluded that particulate matter and ozone caused more than 2.2 million premature deaths each year in G20 countries. Reducing emissions in these countries from power plants alone could reduce that death toll by nearly 300,000 lives by 2040.

Air Pollution Across Borders

The G20 represents 19 of the world’s most economically developed countries and the European Union. This collective accounts for more than 90% of the world’s gross domestic product, more than 60% of the world’s population, and 80% of greenhouse gas emissions.

In an effort to fight climate change, many of these countries set goals to minimize their carbon footprint by reducing fossil fuel combustion. Because fossil fuel combustion produces pollutant emissions that increase concentrations of ozone and fine particulate matter, the clean energy transition could yield public health benefits, too.

To quantify how air pollution from these countries affects public health, the researchers performed computer simulations using meteorological data from the NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office.

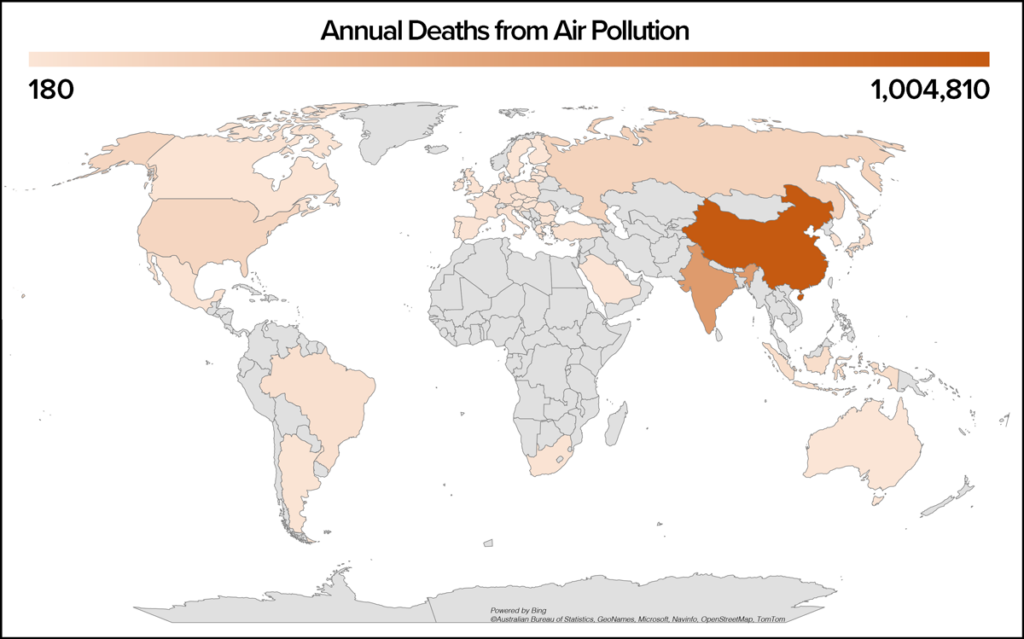

The researchers found that China, India, and the United States, which have high emissions and large population sizes, experience the greatest number of deaths among G20 countries. Still, air pollution knows no national borders, and emissions from one nation affected nearby nations, too.

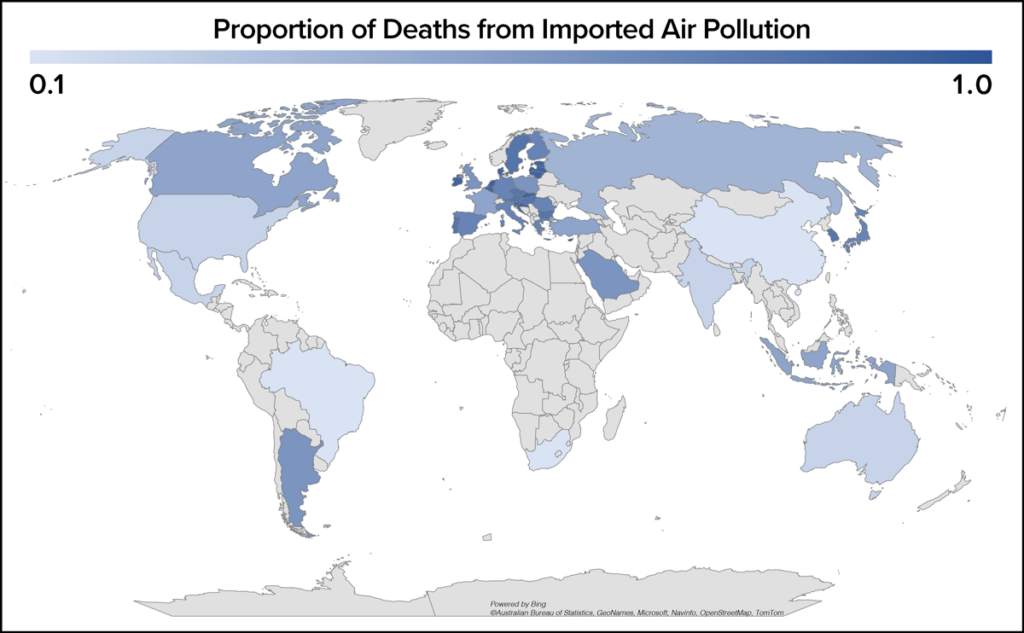

“People can be exposed to air pollution in countries where the pollution didn’t originate due to their geographic location and the prevailing wind patterns,” said Omar Nawaz, an air quality scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder and lead author of the study. “For example, we found that South Korea and Japan were more impacted by emissions from China than they were by domestic pollution sources.”

Reduce Emissions to Save Lives

Nations need to cooperate to realize these life-saving effects.

The team then modeled how many lives could be saved if power plants in G20 countries, which are one of the largest emission sources for air pollution, achieved their net zero goal by their target dates.

They found that by 2040, even before any of these nations reach their net zero goal, reducing emissions from power plants alone would save approximately 300,000 lives each year.

This estimate does not account for sources of emissions other than power plants, and according to the researchers, the health benefits would continue to grow if nations stayed on pace with their goals after 2040 (see Table 1).

Because air pollution crosses political borders, nations need to cooperate to realize these life-saving effects.

“For example, if Canada worked towards reaching their net zero emissions goal, the main country reaping those benefits would be the United States because of its proximity to Canada and larger population size,” Nawaz said. Meanwhile, emission reductions in the United States would also yield public health benefits for Canada.

Using the approach outlined in this study, Nawaz said that scientists could assess how reducing emissions in other sectors such as agriculture could also reduce pollution’s death toll. Applying it broadly could reveal the full life-saving potential of climate change mitigation. (GeoHealth, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GH000713, 2023)

—Kirsten Steinke (@Kirsten_Steinke), Science Writer