Uranus has a sideways orbit, unique weather patterns, and unusual rings, and its moons might have subsurface oceans. A mission to the ice giant has a great deal of scientific potential, and now there’s another compelling reason to visit: Data gathered on the way to the distant world could aid the search for an elusive ninth planet suspected to orbit beyond Neptune.

With current technologies, positional data gathered during the mission’s Jupiter-to-Uranus cruise stage could shrink the search window a thousandfold and make hunting for the planet with high-powered telescopes much more feasible, according to a team of doctoral students at the University of Zürich in Switzerland. Their results demonstrate that NASA’s proposed flagship mission to Uranus could yield scientific discoveries beyond the Uranian system.

Narrowing the Search Grid

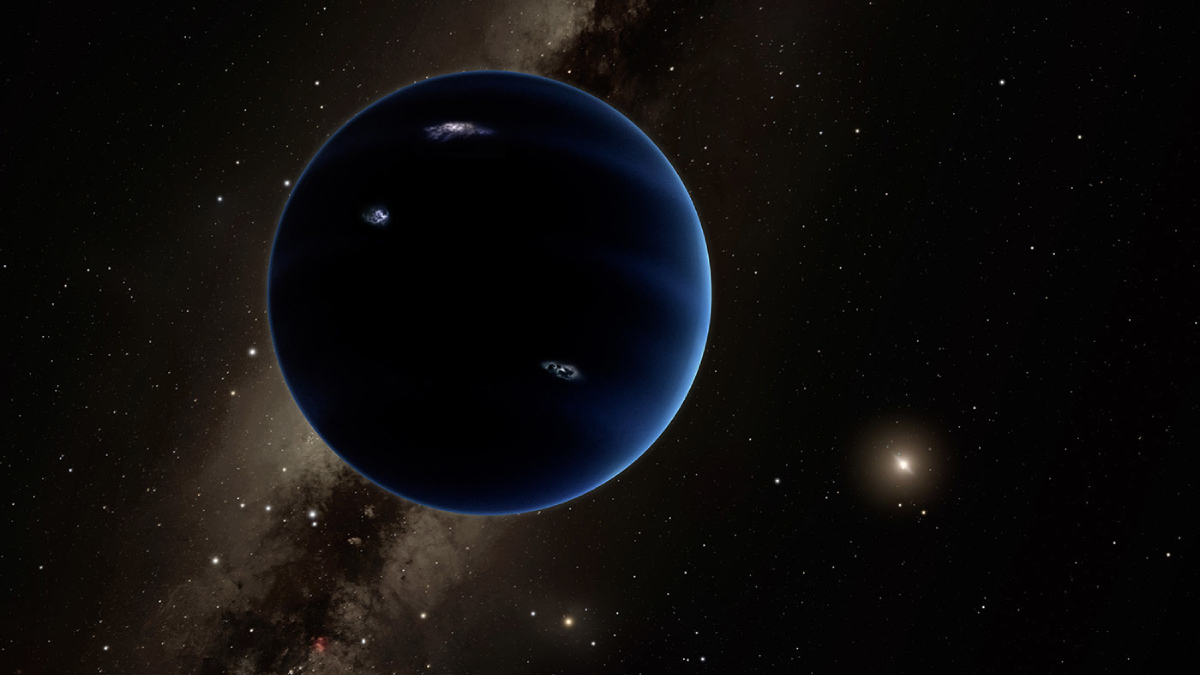

In 2016, two astronomers noticed that the orbits of several small icy objects in the outer reaches of the solar system track too well with each other to be random. Computer modeling and subsequent observations suggested that an unseen body far beyond Neptune’s orbit might be gravitationally shepherding those objects into alignment. The astronomers dubbed the hypothesized body Planet 9 and have been trying to pinpoint its location ever since. (Not all astronomers are convinced.)

The planet, if it’s out there, would be very faint. However, the high-powered telescopes that could find it have narrow fields of view, suited for pinpoint targeting rather than sweeping searches. Astronomers would need to know exactly where to look, explained coauthor Jozef Bucko, and as of now the search grid covers too large a swath of sky to earn highly coveted telescope time. “To persuade the observational astronomers to focus a telescope and try to search for it—this is very expensive, and we need to have strong arguments.”

That’s where the proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission comes in. During its travels to the outer solar system, it would occasionally ping a receiving station on Earth to let technicians know where it is, how fast it’s going, and the status of onboard systems. This is standard procedure. Mission teams use these kinds of ranging data to keep a spacecraft on course; anything with enough gravitational influence—such as planets, asteroids, and comets—could nudge it off its path.

“If there is a gravitational anomaly in the solar system, in this case, Planet 9, the trajectory of the spacecraft would be affected,” said coauthor Deniz Soyuer. The planet’s gravity would subtly tug the spacecraft toward it, registering as a small change in speed or direction during the craft’s 10- to 15-year cruise toward Uranus. Given the theorized mass and distance of Planet 9—6.3 Earth masses and 460 times the Earth–Sun distance—the planet “will definitely have a nonnegligible effect on the trajectory of a spacecraft,” they said.

It’s a thousandfold improvement over what was possible with Cassini traveling just out to Saturn.

The idea of using spacecraft ranging data to find Planet 9 has been around for a few years, explained astronomer Mike Brown of the California Institute of Technology, who coproposed the idea for Planet 9 in 2016. Astronomers tried using ranging data from NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn to pinpoint the planet but were left with too much of space to check.

“This paper gives a nice twist on the idea by tracking the spacecraft over a wide range of distances,” said Brown, who was not involved in the study. The spacecraft would traverse more than 2 billion kilometers (1.2 billion miles) between Jupiter and Uranus. “One bit of good news is that the greater the distance [from Earth], the greater the effect of Planet 9, so making it all the way out to Uranus gives you quite a bit of leverage,” he said.

The researchers calculated that if a Uranus mission uses Cassini era technology, data from its cruise phase could narrow the search grid to 0.2 square degree. It’s still a large swath of the sky, the team said, but a thousandfold improvement over what was possible with Cassini traveling just out to Saturn.

If more modern technology can reduce the noise level of the ranging data, the search grid could shrink another 20 times smaller, the team said. “You don’t really need that much of an improvement to be able to localize [Planet 9] to a place where you can convince people to point their telescopes at it,” Soyuer said. This research was presented at the 2023 European Geosciences Union General Assembly and was submitted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Creative Solutions

A large uncertainty in how precisely ranging data could locate Planet 9 is not the technology on board the spacecraft, explained coauthor Lorenz Zwick, but rather limitations back on Earth. Ranging data are often gathered infrequently during a long cruise stage as a cost-saving measure.

“I think it is great that people are thinking creatively about different ways in which we could eventually track down this elusive planet on the edge of the solar system.”

The more frequently scientists collect ranging data, the more precisely they can home in on Planet 9, Zwick said, as well as accomplish other science unrelated to Uranus. The benefits of frequent data gathering would far outweigh the costs, the researchers argued.

Bucko acknowledged that their model was a simple proof of concept that considered only the gravitational influences of the Sun and the outer solar system planets. The group plans to run more complex calculations that include the influences of other solar system bodies, and they hope to test their model using data from NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto, Soyuer said.

“I think it is great that people are thinking creatively about different ways in which we could eventually track down this elusive planet on the edge of the solar system,” Brown said.

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@AstroKimCartier), Staff Writer