If it seems like humans are great at polluting, it might be because we’ve had a long time to practice: Classical civilizations started polluting the region around the Aegean Sea with lead some 5,200 years ago, according to a new study. The finding is one of the earliest detections of lead pollution in the world and shows that Greek civilization was capitalizing on the resource long before being conquered by resource-hungry Rome.

“[This] is a turning point in human environmental history.”

Thousands of years later, lead pollution became so extensive that it left a mark not just on land, but also on the sea. The new study reports a never-before-seen lead spike in marine sediments about 2,150 years ago, during a time when Rome was making incursions into Greece, suggesting that the civilization’s profound regional impacts extended to the marine environment.

The lead spike associated with ancient Roman expansion “is a turning point in human environmental history,” said Earth scientist and study author Andreas Koutsodendris of Universität Heidelberg. With the Romans, the authors argue, human activity displaced natural forces as the dominant factor driving environmental change in the Aegean.

Ancient Pollution

Lead is a natural, and toxic, element in Earth’s crust. It wreaks havoc on the liver, kidneys, and brain, and is especially harmful to children.

That’s unfortunate because lead is very useful. It will melt over the heat of a campfire and is soft enough to easily form into sheets and tubes. Romans used lead for practically everything, from plumbing to sweetening their wine. The word “plumbing,” in fact (as well as lead’s chemical symbol, Pb), is derived from the Latin word for lead, plumbum. Lead is also a by-product of smelting silver, the primary metal that Romans and Hellenistic Greeks used for coins.

Processing lead (and smelting silver from the lead-rich mineral galena) releases small particles of the metal into the air, where they can travel extraordinary distances.

Koutsodendris and his colleagues became interested in ancient lead pollution as a way to understand when humans started driving large-scale environmental change. The Aegean, home to some of Europe’s earliest civilizations—and Koutsodendris’s homeland, Greece—was a natural place to go looking for lost chapters of this environmental story.

Because lead is naturally scarce, it’s a good tracer of ancient human activity, said hydrologist Joseph McConnell of the Desert Research Institute, who has studied ancient lead pollution but was not involved in the new study.

Researchers have traced lead pollution in Europe back to the Bronze Age (about 3600–1200 BCE), according to geochemist Jack Longman of Northumbria University, who reviewed the study published in Communications Earth and Environment. Longman and his colleagues previously reported lead pollution from Serbia’s Crveni Potok peat bog dating to the very early Bronze Age, about 5,600 years ago.

In addition, McConnell and his colleagues previously showed that lead levels in ice cores from Greenland closely track mining activity in Europe over thousands of years, complete with ups and downs reflecting political expansions, wars, and plagues.

But these and other records of ancient lead pollution come almost exclusively from land. Koutsodendris and his colleagues wanted to know when human activity first left a mark on the seas. Without a marine record, we’re missing an important chapter of the story of how our species left its mark on the world.

Beyond revealing evidence of human impacts at sea, marine cores offer another advantage, said McConnell. On land, sediments accumulate lead transported from far and wide via particles in the air, so terrestrial sediments record a mix of local and global influences. But marine sediments are less sensitive; small-scale local lead mining or massive mining operations on a faraway continent wouldn’t leave as much of a mark. Marine sediments from the Aegean should therefore preserve a more regional story of human activity.

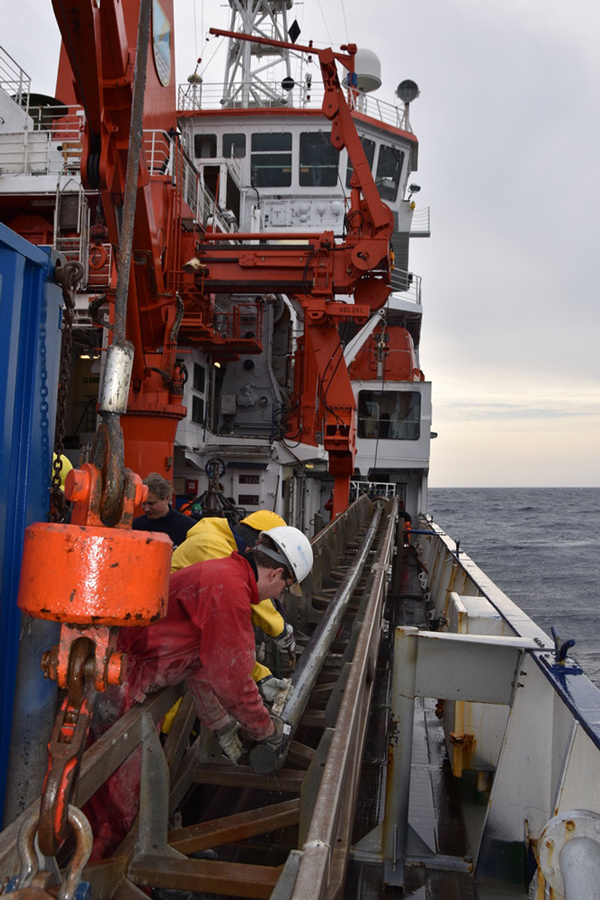

Koutsodendris and his colleagues looked to sediment cores they had drilled over the past 20 years from seafloor sites across the Aegean to find lead. They also collected a core from Tenaghi Philippon, a peatland in northeastern Greece. To date the samples, the team measured radiocarbon isotopes of tiny plankton shells preserved in the sediments.

The ancient Greeks were polluting their environment long before the Romans arrived, but on a much smaller scale.

The new data revealed a striking spike in marine lead pollution about 2,150 years ago. That’s around the time when polities in what is now Greece were being incorporated into the Roman Republic, suggesting that the more intensive, monetized economy of the Romans left a serious mark on the Aegean regional landscape. The date agrees well with other records that show similar lead peaks associated with the rise of Rome, McConnell said.

Before this peak, there was no detectable lead pollution in marine samples. But the terrestrial core from Tenaghi Philippon contained a lead spike dating back to the Bronze Age. The ancient Greeks were polluting their environment long before the Romans arrived, but on a much smaller scale.

“This is an interesting and important contribution,” McConnell added.

“It’s great they’re filling in the gaps” in the story of human impacts on the environment, Longman said. “Their work on Greece is the first I know of which looks into the levels of pollution released by the ancient Greeks—a very important culture when it comes to human development.”

—Elise Cutts (@elisecutts), Science Writer