For years, the amount of dust in the atmosphere over West and South Asia has decreased. Now, research suggests that rising temperatures in the Arctic may be the cause.

As Arctic ice melts, darker ocean and land surfaces reflect less sunlight and absorb more heat. That excess heat melts more ice, exposing more surface area and amplifying warming.

It’s like wearing black clothes on a hot day, said atmospheric scientist Meng Gao of Hong Kong Baptist University.

In the new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Gao and his colleagues suggest that all that warming is weakening the winds that carry dust from the Middle East toward South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

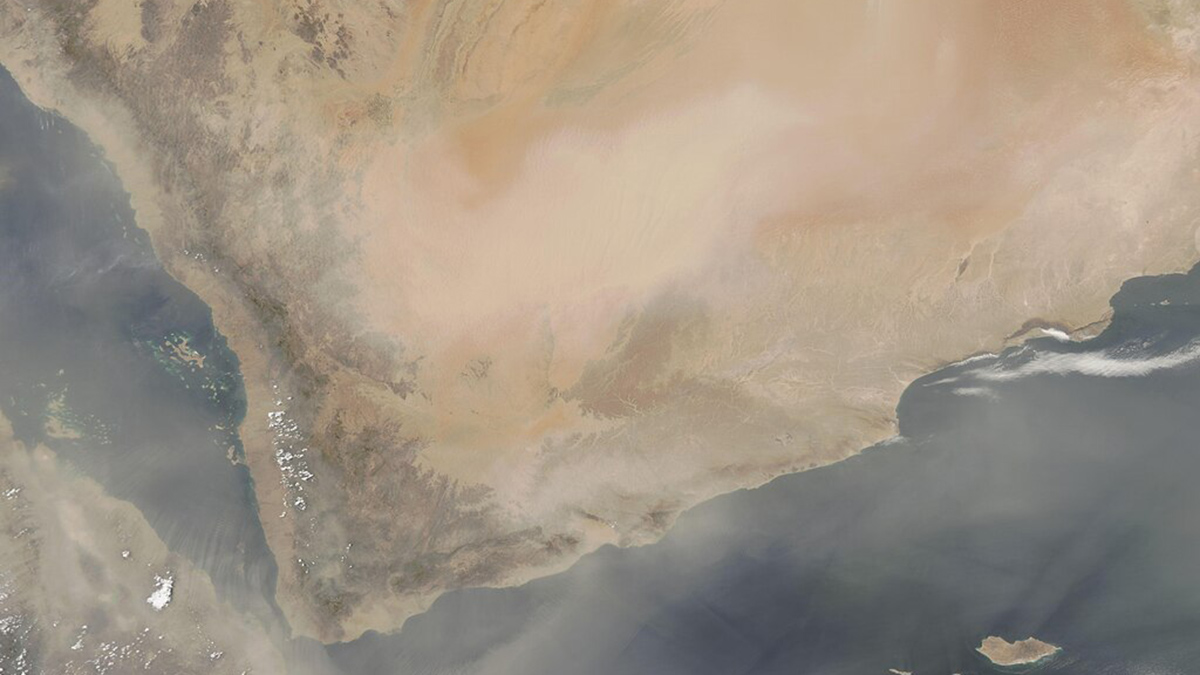

The researchers made the discovery while scouring satellite data for trends in atmospheric dust between 2008 and 2019. They compared these dust patterns and weather data to climate simulations depicting how dust loads change in response to anthropogenic factors such as greenhouse gas emissions (the primary cause of Arctic warming) and changes to land use. Climate simulations driven by greenhouse gases most closely matched the observed wind patterns and dust loading data.

The team found that as the Arctic has heated up, the winds have died down because of the reduced temperature contrast between Arctic regions and the midlatitudes.

Changes in wind patterns also increased precipitation in the Middle East. Rain and soil moisture keep dust particles on the ground. Combined, those factors caused less atmospheric dust to blow in from areas such as the Arabian Peninsula and the Thar Desert, which have historically been major sources of the dust that makes its way into West and South Asia.

A Dusty Future?

On the surface, it might seem like a decrease in atmospheric dust is a good thing—and it does have benefits. Reducing dust in the air improves air quality, potentially lowering the rate of respiratory illnesses. More than 500 million people in India alone regularly experience poor air quality due to sand and dust storms, according to a 2021 report by the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. But atmospheric dust also cools the land surface because it scatters and absorbs radiation, so falling dust levels could add to rising temperatures.

The new understanding of the effects of Arctic amplification provides “a way forward for models to reproduce better how dust is changing.”

It’s hard to say whether the trend of falling dust levels will hold in years to come. Historically, climate models have struggled to reproduce past variations in atmospheric dust concentrations, said Jasper Kok, an atmospheric physicist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved with the study. But the new understanding of the effects of Arctic amplification provides “a way forward for models to reproduce better how dust is changing,” he said.

Understanding dust levels could help scientists manage future air quality threats. Some existing models predict that in a carbon-neutral future, dust levels in West and South Asia could increase again because winds carrying dust from the Middle East could become stronger. If Arctic temperatures return to preindustrial levels, wind patterns might stabilize and return to their former state, carrying new dust with them. “Anything [can have] side effects,” Gao said. “We need to be very careful. Anytime we decide to do something, we need to take a comprehensive look.”

—Skyler Ware (@skylerdware), Science Writer

This news article is included in our ENGAGE resource for educators seeking science news for their classroom lessons. Browse all ENGAGE articles, and share with your fellow educators how you integrated the article into an activity in the comments section below.