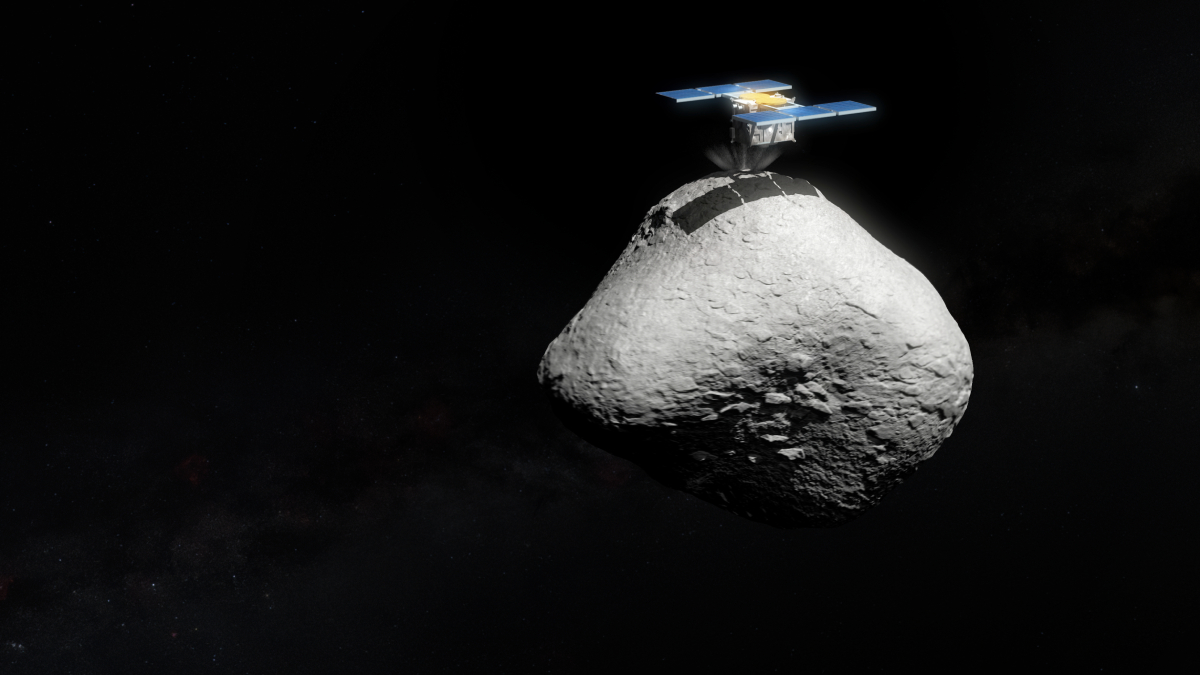

In 2018, the Hayabusa2 mission successfully encountered asteroid Ryugu. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) spacecraft arrived at, touched down on, collected samples of, and lifted off from the asteroid. It returned samples to Earth in 2020.

With plenty of fuel left for its extended mission, called Hayabusa2# or “Hayabusa2 Sharp,” the spacecraft raced off to its next objective, a high-speed flyby of asteroid 98943 Torifune in 2026. If all goes well with that rendezvous, the craft will attempt its final objective: an encounter with and touchdown on asteroid 1998 KY26 in 2031.

But that final objective may prove more difficult than initially imagined. New ground-based observations of 1998 KY26 have revealed that the asteroid is 3 times smaller than previously thought and spins twice as fast.

“We found that the reality of the object is completely different from what it was previously described as,” Toni Santana-Ros, lead author of a new study on 1998 KY26 and an asteroid researcher at Universidad de Alicante and Universitat de Barcelona in Spain, said in a statement.

Small and Fast

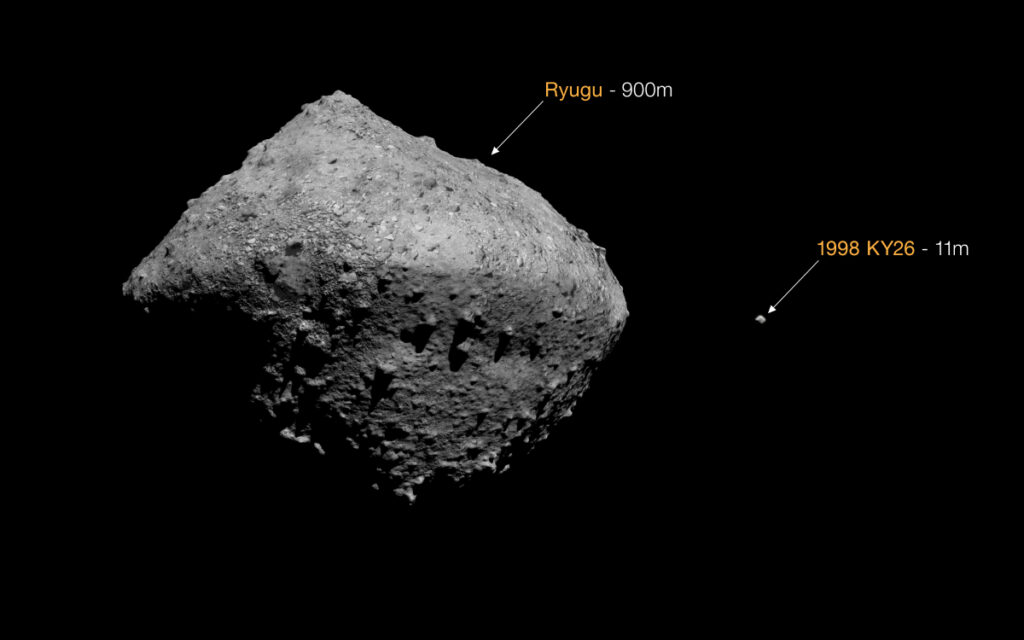

Astronomers discovered 1998 KY26 in 1998 when it came within 2 times the Earth-Moon distance. Radar and visual observations shortly after discovery estimated that the asteroid was about 30 meters across and rotated once every 10.7 minutes, the fastest-rotating asteroid known at that time. As the asteroid moved away, it became too faint to see for more than 2 decades. When Hayabusa2’s mission scientists selected targets for its extended mission, they relied on those 1998 calculations.

The asteroid completes one spin every 5 minutes and 21 seconds, less time than it takes to listen to Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

Finally, in 2024, 1998 KY26 came close enough to Earth—12 times the distance to the Moon—to observe again. Using four of the most powerful ground-based telescopes available, Santana-Ros and his colleagues watched the diminutive asteroid tumble and spin from multiple angles, allowing them to calculate a more accurate spin rate than was possible with the limited radar and photometry in 1998.

They calculated that the asteroid completes one spin every 5 minutes and 21 seconds, less time than it takes to listen to Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” The team then combined those new observations with the 1998 radar data to recalculate the asteroid’s size. They found that instead of being roughly 30 meters in diameter, 1998 KY26 is just 11 meters, or about the length of a telephone pole. The team published these results in Nature Communications on 18 September.

“The smaller the asteroids get, the more abundant they are—but that also means that they are harder to find,” explained Teddy Kareta, a planetary scientist at Villanova University in Pennsylvania who was not involved with the new discovery. “The fact that this new paper finds such a small size for KY26 is tremendously interesting on its own—Hayabusa2 will be able to explore an extremely understudied population—but it also means that we might not have a tremendous number of known objects to compare to as well.”

A Challenge and an Opportunity

The new size and spin measurements of 1998 KY26 will make Hayabusa2’s planned touchdown more challenging, the researchers wrote. However, this is not the first time that an asteroid rendezvous mission has had to adjust its expectations mid-flight. Both Ryugu and Bennu, the first target of NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security–Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission, had rougher surfaces than expected, requiring the respective missions to adjust their sample collection methods. Too, the OSIRIS-REx team learned that Bennu was actively spitting out material only when the spacecraft got close, which led them to change their plan for orbital insertion.

Despite the new challenges with 1998 KY26, Hayabusa2#’s team has a big advantage: 6 years to rework their game plan.

“The Hayabusa2 team are incredibly smart, hardworking, and have a ton of experience under their belts, but I’m sure that this kind of result is causing a bit of hand-wringing and concern for them even if the spacecraft is fully capable,” Kareta said.

“We have never seen a ten-metre-size asteroid in situ, so we don’t really know what to expect and how it will look.”

“I’m sure even the team has their doubts about whether or not the original plan was possible, but if I had to bet money, I still think the team will try [to touch down],” they added. “You set yourself up for success by building a great spacecraft and collecting a great team of engineers and scientists to staff it, but it’s still a bet every time you try something new.”

Even if a touchdown on 1998 KY26 ultimately proves impossible and Hayabusa2# simply flies on by, asteroid scientists will still gain valuable information about an incredibly common but hard-to-spot type of small asteroid.

“We have never seen a ten-metre-size asteroid in situ, so we don’t really know what to expect and how it will look,” Santana-Ros wrote.

“In many ways, a spacecraft visit to it now is even more exciting than it was before,” Kareta said.

—Kimberly M. S. Cartier (@astrokimcartier.bsky.social), Staff Writer