Climate change is hitting the American Southwest hard, bringing warmer temperatures, longer droughts, and dwindling water supplies. For Native American tribes in the region, these changes are threatening their ability to live on the land in the way that they have done for hundreds, or even thousands, of years.

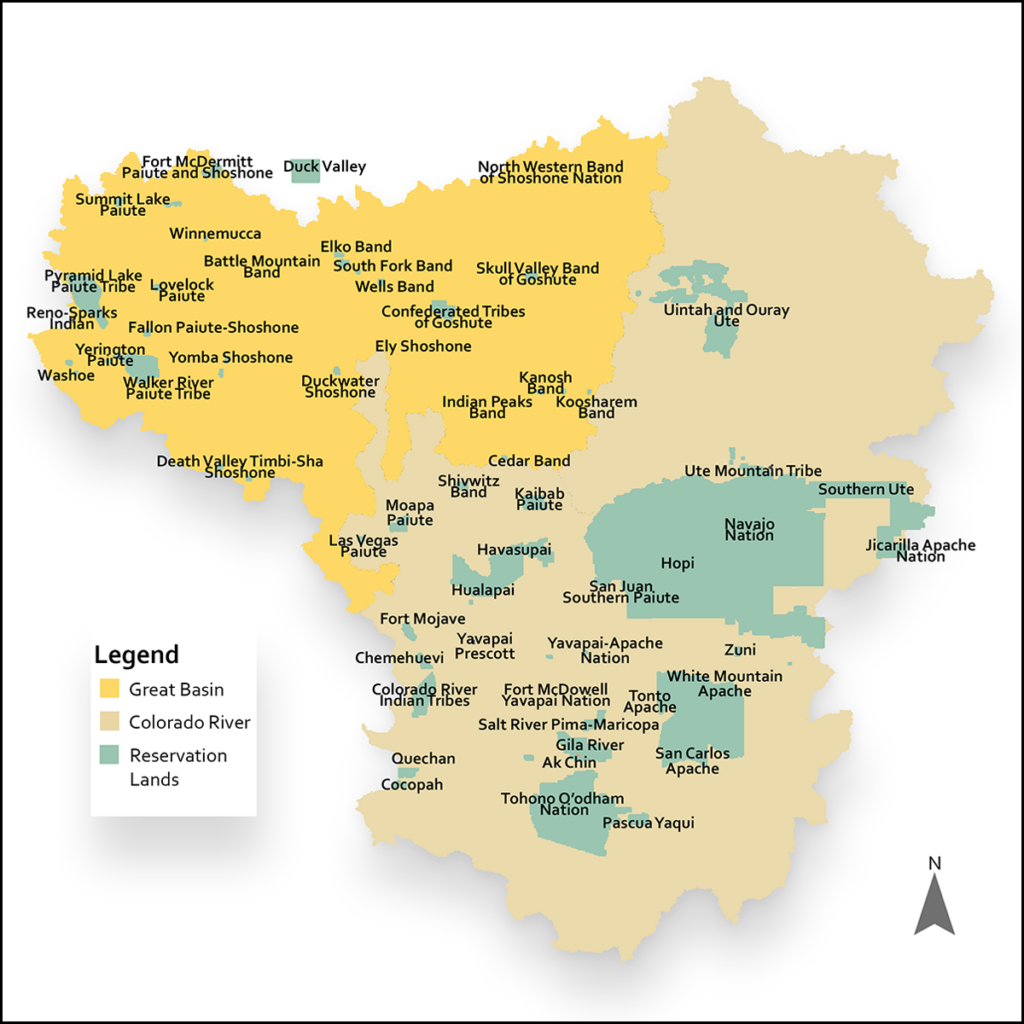

In response to these challenges, many of the tribes have developed their own climate change adaptation initiatives, and to see how Western science could help in these efforts, the U.S. Department of Agriculture funded the Native Waters on Arid Lands project in 2015. The goal of the project was to partner researchers with tribal communities in the Great Basin and American Southwest to collaboratively understand how climate change was affecting the region and to come up with possible paths to adaptation.

Early in the project, Western researchers acknowledged the importance of looking to tribal communities to take the lead in the collaboration. “It was recognizing that Indigenous communities are some of the experts in this field and are a little bit more ahead of the curve when it comes to identifying barriers to adaptation,” said Helen Fillmore, a researcher at the University of Nevada, Reno, and a member of the Washoe Tribe.

Consequently, in 2016 and 2017, Fillmore and her colleagues conducted two surveys to assess the type of information and data that would help Indigenous communities in their efforts to build climate resilience. Fillmore intentionally chose a questionnaire-style format because she recognized that her training in Western science carried with it certain assumptions. “We wanted to investigate this topic as a survey to make sure that we weren’t importing our own bias into it,” Fillmore said. “We want to develop a better understanding of their priorities, so that we can work and engage with them in a more meaningful way.”

Challenging Assumptions

Tribal government employees, agriculturalists, researchers, and outreach professionals engaged in climate adaptation and resiliency efforts on reservation lands completed the 50-question questionnaires—tribal members made up three quarters of the 98 respondents.

The results were sometimes surprising. Fillmore will be talking about the findings as one of the presenters at “Addressing Community Needs for Building Capacity to Use Earth Observations for Atmospheric Systems” on 13 December at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2021.

The survey found that the highest priority ratings were for information related to climate adaptation on reservation lands and for information related to the role of Traditional Knowledge in climate adaptation. “Being able to integrate Traditional Knowledge when it comes to climate change adaptation or natural resource management is very important when it comes to the resiliency of these communities,” Fillmore said.

The researchers had assumed that in the arid Southwest, the highest priority would be for data on water availability. Instead, participants indicated that data about water quality were more important to them than data on streamflow, precipitation, or snowpack. Fillmore believes these priorities could reflect that few data about water quality in the context of climate change are available to the communities in question.

Geographer Casey Thornbrugh, a citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the tribal climate science liaison at United South and Eastern Tribes, shared that water quality is also a top concern for tribal nations in the Northeast. “Water quality is a tremendous issue, especially for tribal nations that are on rivers, or in coastal areas, where they’ve seen water quality deteriorate over the past century,” Thornbrugh said. “There are tribal nations that have fish consumption advisories out because they can’t safely eat their traditional foods.”

The Importance of Asking First

The survey also asked where participants were accessing their climate-related information. It found that the highest-rated sources were ones local to the Indigenous communities, such as tribal natural resource departments, farmers, ranchers, and Traditional Knowledge holders. “I think it goes to show kind of how much more important it is to put resources at that local level,” Fillmore said. “When more resources go outside of the tribe, it creates a bigger disconnect when it comes to accessing them.”

“I think it’s shown that it’s always good to be humble and to ask questions first, before starting to pursue something that isn’t going to be needed or isn’t going to be relevant to the communities that you’re working with.”

The finding indicated that it is not just the information that is important, but where that information is located and how accessible it is, Fillmore said. Providing the most useful information and data and making them easily accessible support tribal sovereignty, a critical factor when it comes to building resiliency to climate change, she said.

Thornbrugh concurs. It is important that sovereign tribal nations are respected as leaders on adaptation strategies on their lands because they possess the knowledge of those lands and are the most affected, he said. “And it is about making sure that people are afforded dignity to lead in the solution.”

Overall, researchers said, the survey revealed surprising results that underlie the value in asking, rather than assuming, what information or data might be helpful for Indigenous communities in adapting to climate change. “I think it’s shown that it’s always good to be humble and to ask questions first, before starting to pursue something that isn’t going to be needed or isn’t going to be relevant to the communities that you’re working with,” Fillmore said.

—Jane Palmer (@JanePalmerComms), Science Writer