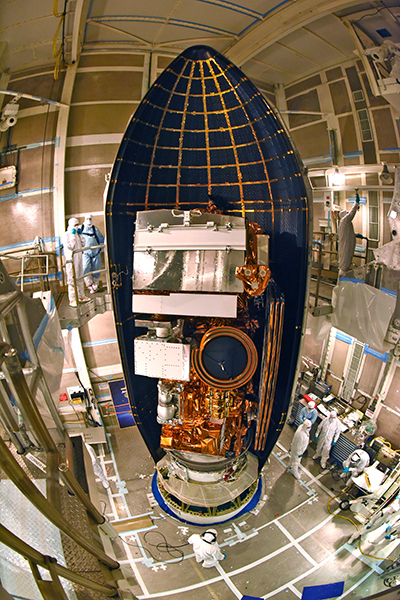

With Saturday morning’s successful launch of the Joint Polar Satellite System-1 (JPSS-1) from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, this next-generation polar-orbiting satellite “is arriving just in time,” according to Steve Volz, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Satellite and Information Service..

The satellite, whose name changed to NOAA-20 after launch, is outfitted with a suite of five sophisticated instruments that will produce data critical to forecasting extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, out to 7 days. The instruments also will track other aspects of Earth’s environment, including reflected sunlight and emitted thermal radiation, ocean and coastal water quality, volcanic eruptions, and the size of the ozone hole over Antarctica.

“The main contribution” that NOAA-20 provides flying in coordination with Suomi NPP is that there will be a primary and spare satellite. “We will not be vulnerable to a single-point failure of this critical system.”

The deployment of NOAA-20, now orbiting the planet from pole to pole about 825 kilometers above Earth, also has greatly reduced the potential for a worrisome gap in crucial weather data. The spacecraft shares the same orbit and trails 50 minutes behind another polar-orbiting satellite launched in 2011 and known as Suomi NPP (National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS) Preparatory Project). Suomi NPP began as a research mission to test new technology but was pressed into operational service in 2014. NOAA and NASA collaborate on the JPSS program, the civilian successor to NPOESS, which was beset by cost overruns and delays.

NOAA-20 “will bring you the latest and best technology NOAA has ever flown operationally in the polar orbit to capture more-precise observations of the Earth’s atmosphere, land, and waters,” Volz said at a 12 November news briefing.

He added that “the main contribution” that NOAA-20 provides flying in coordination with Suomi NPP is that there will be a primary and spare satellite, with NOAA-20 being the primary one. “We will not be vulnerable to a single-point failure of this critical system.”

The European Meteorological Satellite Organization operates a similar polar satellite program. “Together, all of these polar-orbiting satellites provide over 80% of the data that goes into our numerical weather forecasts,” Greg Mandt, director of NOAA’s Joint Polar Satellite System, said at the briefing. “We all feel the impact of these data in our lives in terms of good weather forecasts.” Those satellites also work in tandem with NOAA’s geostationary satellites, including Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-16, which launched in November 2016.

Advanced Instrument Suite

NOAA-20 carries such instruments as the Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS), which can monitor sea ice change in polar regions, generate global maps of precipitation, and provide information on atmospheric temperature and water vapor, said Mitch Goldberg, NOAA chief program scientist for JPSS. The mission’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), he added, is used for environmental assessments, including of sea surface temperature gradients, ocean and coastal water quality, floods, fire, smoke, and volcanic eruptions. VIIRS achieves spatial resolution “so high that you can actually pinpoint the center of a hurricane within [about] 20-meter accuracy,” which, he said, is important to know for hurricane models.

Other instruments include the Cross-Track Infrared Sounder, which profiles atmospheric temperature, pressure, and moisture in three dimensions; the advanced Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite, which monitors the ozone layer; and the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System instrument, which gauges Earth’s radiation budget. The launch of NOAA-20 also lofted into orbit several CubeSats, including the Microwave Radiometer Technology Acceleration demonstration CubeSat mission, which Volz described as a demonstration of the potential “next-generation approach to do microwave sounding in a smaller form fit factor than we have on ATMS.”

“Weather and climate are really linked at the hip, and JPSS will provide, whether you want it or not, great progress in both areas.”

Instruments on NOAA-20 also will help with climate monitoring, according to Lars Peter Riishojgaard, Integrated Global Observing System project director for the World Meteorological Organization. “Sometimes the political money likes to fund observations and models and research for climate, [and] sometimes the political money likes to do weather,” he said at an October briefing in Washington, D. C. “Weather and climate are really linked at the hip, and JPSS will provide, whether you want it or not, great progress in both areas.”

Budget Uncertainties for Polar Follow-On Missions

NOAA-20 is the first of four planned JPSS program satellites, with the launch of JPSS-2 planned for the first quarter of fiscal year (FY) 2022. Appropriation levels for two additional Polar Follow-On (PFO) missions—JPSS-3 in FY 2026 and JPSS-4 in FY 2031—remain of concern to Congress and members of the weather community.

NOAA spokesperson John Leslie told Eos last week that the FY 2017 appropriations funding supported the continued development of the PFO satellites, as does the continuing resolution for FY 2018 (which was pegged at the FY 2017 level). He added that the White House’s proposed budget, the House of Representatives’ intended $50 million for the program, and the Senate’s intended $419 million all continue support for the PFO program, although with significantly different interim budget levels requiring reconciliation. “We are awaiting further guidance from Congress. The Congress has been a vocal and strong supporter of NOAA’s weather mission and the satellite observing systems that enable it,” Leslie said.

“We should be very risk averse when considering any manipulation to the current plans of continuing to acquire polar data.”

The Trump administration’s FY 2018 budget bluebook for NOAA outlines a request of $180 million to continue development activities for the two PFO missions, which is a decrease of $189.3 million. The document states that the agency will identify new launch dates and “will initiate a re-plan” of the PFO program “while seeking cost efficiencies, managing and balancing system technical risks, and leveraging partnerships.” However, in a 27 July appropriations bill, the Senate Committee on Appropriations “strongly” rejected the administration’s proposed PFO budget cut, stating that it and the unspecified postponement of the PFO satellites “would introduce a weather forecasting risk that this Committee is unwilling to accept.”

Ari Gerstman, director of Washington operations for the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, told Eos that the Senate committee’s language “reflects the broad consensus shared by most in the weather community, that polar-orbiting data are critical to the nation, and we should be very risk averse when considering any manipulation to the current plans of continuing to acquire polar data.”

—Randy Showstack (@RandyShowstack), Staff Writer

Citation:

Showstack, R. (2017), Polar satellite launch eases concerns of weather data gap, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO087257. Published on 20 November 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.