Caves have long been used as places of shelter, burial, and ritual. Now, researchers have analyzed stalagmites from two caves in southwestern Turkey and found that they contain layers of soot and charcoal, presumably from human-set fires. By precisely dating the stalagmite layers bracketing this black carbon, the scientists estimated that people were exploring these caves thousands of years ago. These results reveal how geophysical data can complement archaeological records, the team concluded.

The Allure of Caves

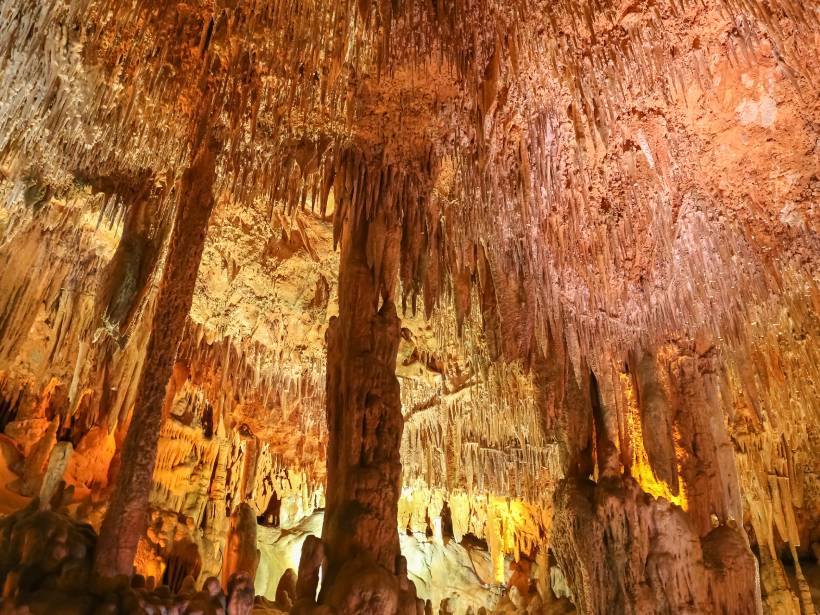

To many ancient cultures, the dark passageways of caves represented a metaphorical connection to another world. Even today, with the advent of powerful flashlights that slice through darkness, caves are still alluring—the National Speleological Society, a nonprofit organization devoted to cave exploration, counts more than 7,000 members. “They’re special places,” said Koray Koç, a paleoclimatologist at Akdeniz University in Antalya, Turkey.

In 2015, Koç and his colleagues headed underground to explore several caves in southwestern Turkey. Spelunking is always an adventure, said Koç, and these trips were no exception. In one cave, the team had to shimmy though an extremely narrow passageway barely wider than a person, and they found human and animal remains in addition to pieces of pottery.

Natural Record Keepers

Koç and his collaborators observed many stalagmites and stalactites. Because speleothems like these grow slowly over time, they’re record keepers of past environmental conditions: Scientists have used them to reconstruct droughts and climate variability, among other changes. Koç and his colleagues collected 16 stalagmites, the shortest about the length of a pinkie finger and the longest topping a meter.

Back in the laboratory, the scientists split the stalagmites lengthwise to reveal their interior layers. They were astonished to find that 14 of the stalagmites were shot through with black layers of soot and charcoal up to a millimeter thick and easily visible to the naked eye. That discovery changed the direction of the investigation, said Koç.

The researchers had initially been planning to use the stalagmites to reconstruct the ancient climate in the region. “Our main purpose was to collect clean and suitable samples for paleoclimate research,” said Koç. But now the hunt was on to better understand these layers.

Koç and his colleagues focused on three stalagmites from Tabak Cave and Kocain Cave with particularly well defined black layers. These layers reveal a human presence in these caves, the researchers suggest.

Evidence of Fires

The black layers in the speleothems are the result of people carrying torches or setting fires in the caves, Koç and his collaborators say. Combustion releases particles of black charcoal that hitch a ride on air currents, and in a cave, some of these particles are bound to end up sticking to growing stalagmites. (The same effect can be seen today on the stone surfaces of old buildings exposed to pollution.)

The researchers estimated the ages of the speleothems’ normal layers using uranium-thorium dating. By tabulating the ages of layers adjacent to each band of soot and charcoal, they estimated when the black carbon was deposited and therefore when humans were exploring these caves.

A Summer Refuge?

“People might have used these caves as a shelter during the summer.”

Koç and his colleagues found three layers of soot and charcoal in the stalagmites from Tabak Cave. They dated the layers to roughly 6,700, 7,100, and 7,400 years before present (i.e., before 1950 CE), with an uncertainty of about 200 years. That’s surprisingly early, said Koç, but it makes sense that people were inhabiting these caves. Turkey is notoriously hot in June, July, and August, so maybe these caves functioned as a refuge from the heat, he said. “People might have used these caves as a shelter during the summer.”

It’s unlikely that these layers of black carbon are due to nonanthropogenic triggers like far-away wildfires, the researchers suggest. That’s because the ventilation in Tabak Cave is poor—airborne particles circulating aboveground probably wouldn’t have traveled far into the cave. (The stalagmites the researchers analyzed were tens of meters—and several narrow passageways—beyond the entrance.) Furthermore, archaeological artifacts like pottery sherds found in Tabak Cave confirm a human presence deep underground that probably needed a source of light.

“In archaeological studies, the trickiest part is getting robust ages.”

The stalagmite from Kocain Cave exhibited a wider spread in the ages of its five soot and charcoal layers: 470, 810, 1,500, 1,700, and 2,800 years before present. It’s possible that some of these layers derive from aboveground fires, the researchers acknowledge, because of Kocain Cave’s wide, open entrance and lack of narrow passageways.

These results are an important demonstration of the value of geophysical data, said Koç. The ability to precisely age date a speleothem has the potential to be a boon to archaeology, he said. “In archaeological studies, the trickiest part is getting robust ages.”

Breaking Down Barriers

Ségolène Vandevelde, an archaeologist who studies speleothems at the University of Paris 1 – Pantheon-Sorbonne, agrees. This work breaks down barriers between geological and archaeological approaches to science, said Vandevelde, who is not involved in the research. “Speleothems are often used as environmental and paleoclimate archives. Here, [scientists] use them as an archaeological record.”

These results were published last year in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

There’s a lot more information that can be mined from these speleothems, said Vandevelde. “It’d be really interesting to synchronize all the different sequences of the Tabak Cave speleothems to reconstruct a complete chronology of human occupation in the cave.”

—Katherine Kornei (@KatherineKornei), Science Writer

Citation:

Kornei, K. (2021), Sooty layers in stalagmites record human activity in caves, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO154717. Published on 16 February 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.