Even a cursory glance at how Google operates will uncover the secret sauce behind many of their innovative ideas and products: the design sprint, a regimented 5-day process intended to accelerate progress toward key business questions, product development, or other goals. According to GV (formerly Google Ventures), which developed the concept, the design sprint is “a ‘greatest hits’ of business strategy, innovation, behavior science, design thinking, and more.”

Design sprints have primarily been employed by companies, but could this approach be useful for, say, the Earth and space science community?

That’s a question a colleague and I entertained recently after finding out our proposal to the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) to lead a team on an ambitious and fast-paced project (not quite a loonshot, but not far off) studying the space environment had been accepted. The scope of challenges confronting the project seemed similar to those that Google and other product developers face, so I decided to test whether the sprint could work for space science.

This article shares advice and lessons learned from my experience leading the first of two design sprint–inspired meetings—held this past February at ISSI’s headquarters in Bern, Switzerland—that could be relevant across scientific disciplines.

Warming Up for the Sprint

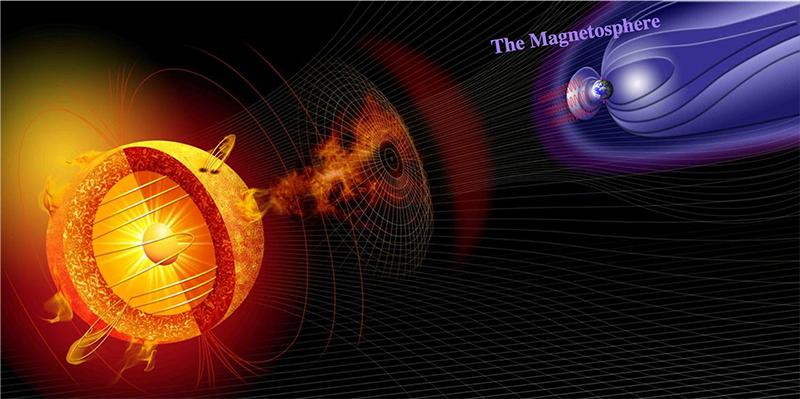

The proposal we wrote to ISSI was to study how energy from the Sun reaches and disrupts the near-Earth space environment. The myriad processes through which this occurs, which sometimes have deleterious effects on our well-being, are known colloquially as space weather (see my TEDx talk on the topic). We specifically proposed to investigate how electric currents carried by particles in Earth’s magnetic field transport energy and momentum between the magnetosphere and the upper atmosphere. This is one of the great unresolved questions in space science—so, you know, a small undertaking for two weeklong meetings.

The angle that won us the award from ISSI was embracing a “new frontier” at the intersection of traditional approaches to space weather research and innovation from data science. In other words, big data + data science + [insert your favorite Silicon Valley buzz phrase here] = radical new understanding. In this relatively undefined space, the possibilities that lay in front of us were huge and sprawling.

In many ways, this was the first time I would be leading a group of people from across the world on a project that we had envisioned. That kind of responsibility comes with stress. As I’m the type to overprepare, my response was to spend long hours leading up to the first week thinking of all the possible paths our team might go down, preparing materials to support each one, and familiarizing myself with the specifics. None of this time was wasted per se, as I learned a great deal, but it was not efficient, nor did much of my preparation end up directly facilitating the team.

Lesson 1. You can’t anticipate exactly where a team will go during a design sprint. (That is the whole point really—to break away from the expected.) For sprint leaders, efficient preparation is key, so spend your time planning for what you know will help your team and avoid a “just in case” mentality that has you planning for what you think might help.

Although it might not be apparent at the outset of a sprint week, know also that each day during the sprint will bring unexpected twists and turns, which will require sacrifices on the part of the leader(s). Be prepared to pivot, adapt, and develop new plans on the fly—staying up late and getting up early as needed—to help the group succeed.

As important as topic-specific preparation is, the importance of team dynamics and logistics cannot be overstated. I suggest off-loading logistical planning to others to the maximum possible extent. Find a facility that provides meeting rooms, amenities, and support staff. Mark my words, there will be challenges to overcome, and you will have difficulties with and tension among team members, but constructive team dynamics flow better and are more easily managed when scheduling and logistics run smoothly.

Sprint Week: Day 1

We arrived at ISSI’s headquarters early on 18 February 2019 ready to sprint. According to the book about the design sprint process, day 1 should be devoted to developing a common understanding among the group, with participants providing their relevant perspectives and engaging in freewheeling discussions.

Lesson 2. Start the week off in an unexpected way to create new ground for your group, and do not steer the discussion.

It’s important not to jump right into technical material. We instead began with a unique icebreaker meant to foster comfort with one another, have some fun, and generally avoid falling into the common scripts to which individuals and groups default. In short, we wanted to preempt normal conversation. Some of the great interviewers of our time do the same (e.g., Terry Gross), and the technique seems to have a way of creating better conversations. In that spirit, I asked each person, What is one thing outside of your field of study or work that you are fanatical about? This question should be open-ended, novel, and lighthearted.

After all my preparation for the week, it was difficult to resist directing the conversation. Doing so would have been a crippling mistake. I often bit my tongue when my mind told me to intervene, opting instead to let these discussions go where they would. I was floored by what I learned as the discussion unfurled in surprising directions. For instance, although we thought we understood each team member’s interests and positions on the basis of material in their publications, conference presentations, and more formal interactions, they raised many unexpected and insightful ideas seemingly disparate from their traditional lines of thought, even on the first day.

Sprint Week: Day 2

Day 2 is about wandering around in your new understanding of the problem space and ideating as a team, as subgroups, and as individuals. This exploratory brainstorming session should be as exhaustive as possible, with everyone contributing—this is when the best ideas emerge. It is important for everyone to be aware of the characteristics of questions that best help ideation. Take advice from “question artists” like Tim Ferriss, Debbie Millman, and Seth Godin. Sometimes the best way to get more out of a discussion is to turn a question on its head.

Lesson 3. Become an artist of the question.

In the context of our topic, for instance, we began with a counterquestion. Instead of asking what we know now about space weather electric current systems, we asked, “What do we not know about the current systems?” It’s a slight but nuanced difference. Suddenly, we were thinking less like traditional space physicists and more like entrepreneurs and designers, amalgamating old and new information in novel ways and making new connections, arrangements, and relationships—all in the name of creating.

Learning the art of asking better questions and fostering a design-centric environment will create fertile ground to sow new ideas. These ideas need support to bear fruit, though, which means having solution-oriented people on your team. You can facilitate this mindset with best practices from other fields, such as the neurological and behavioral sciences and the study of team science.

For example, we used the morning stand-up, a concept adopted from start-up culture that was new to the scientists on our team but drew their praise by the end of the sprint. You can also make life easier on yourself by working with individuals who are open to new ideas. Select your team from among the early adopters and the early-accepting majority rather than the late and laggard adopter groups.

Lesson 4. Work with dedicated individuals who are open to new ideas, rather than those unlikely to budge.

Day 2 made it clear that we had to rely on the dedication and commitment of the team. We were sprinting in Switzerland, with jet-lagged team members who had come from nine different time zones. On top of this, some misfortunes meant that a few people who’d intended to join us in Bern had to participate remotely, often at odd or inconvenient times for them. One team member, for example, punctually joined our meetings from 3:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. her time, breaking only to teach an hour-long graduate course. She was instrumental.

Finally, if you are like me, you seek solitude after long days in deep discussion—and you will be exhausted after day 2. But avoid the temptation to let your team disband that evening and instead schedule a group dinner so that everyone can be together away from the sprint. Group dinners are an important aspect of team culture, which needs to be supportive, open, and enjoyable for your sprint to work.

We spent Tuesday night at a brewery alongside the River Aare, about a 2.5-kilometer walk from our accommodations. Over the next few days, I realized how important this evening was in helping us sustain our camaraderie.

Sprint Week: Day 3

Day 3 of a design sprint involves building solutions around ideas produced during the first two days. The goal is to arrive at a small subset of the most valuable solutions, with paths to those solutions laid out as storyboards.

In our case this step could occur only by working with data. So we introduced yet another relatively new concept for space scientists: the “hackathon.” Most projects will require some activity like this that dictates side-by-side teamwork beyond group discussions. Tailoring this activity to your project and preparing for it by collecting necessary elements (e.g., data and technologies) are vital for getting your group to buy in and ultimately for its success.

Lesson 5. Embrace the hackathon.

The hackathon does two things. First, it facilitates rapid assessment of an immense number of possible solutions, allowing everyone to quickly realize what is and is not possible. Second, it creates action. On day 3, participants typically begin to feel worn and tired, which hurts productivity.

Our group returned from a team lunch lethargic and at risk of falling short of our goal to select two candidate solutions with corresponding plans to achieve them. But we embraced the hackathon. Team members worked together in small groups, sharing data and code to build new data sets and software to help meet our solutions. The directed action and hands-on work helped us to push through our fatigue. That afternoon was one of the most productive of the week.

Sprint Week: Day 4

By day 4, the fruits of adopting and enjoying what were new and (initially) uncomfortable approaches for team members were showing. There was a visceral change in the meeting room during that morning’s stand-up as excitement and coherent plans replaced the reticence and uncertainty of previous stand-ups. It was not always a fluid process, but our success that day was validation that our persistence with these new practices was key.

Lesson 6. Stick to successful new practices.

Day 4 is for poking holes in your approaches and solutions, patching those holes, updating your solutions, and red teaming prototypes. Then you repeat, repeat, and repeat that process. As exhaustion sets in and the week wears on, it is important to build regular progress checkpoints into your efforts, such as roundtable lightning presentations before breaks to collect status updates. There will certainly be problematic issues that have arisen by this point. Checkpoints can help identify these issues before they derail the entire sprint.

Sprint Week: Day 5

The normal, business-oriented design sprint regimen spells out a customer review of a prototyped solution on the final day of the sprint. To this point, we had followed the standard design sprint plan, but by day 5, this no longer exactly fit with our goals as a science team.

Lesson 7. Chart your own path on the final day and beyond.

Over the preceding several days, we had discussed “prototypes” of new particle transport models that might explain the complex magnetospheric processes we are interested in illuminating. But armed with agility and capability from the fresh approach of the week, we had become wildly ambitious. No longer was a solution to just one grand challenge in space weather enough. We also wanted to position this sprint as a foundation for future efforts to tackle other unresolved questions in our field of space science as well as more broadly across other disciplines.

So the ultimate deliverable we premiered to colleagues was an experience-based set of guidelines for how to achieve radical progress in addressing scientific questions. On the final day, we shared these guidelines, alongside the technical solutions we had developed, with colleagues outside our team who joined our meeting virtually. Our sprint had not led to a stopping point but instead had created a “community of practice,” an open, extensible, and cross-disciplinary group that achieves deep knowledge integration and benefits from methodology transfer. Our focus in concluding the sprint was therefore not only on providing the near-term deliverables related to the particle transport models we’d discussed but also on curating the week’s resources, making them usable into the future, and identifying long-term directions.

Lesson 8. Knowledge capture in the moment is critical.

Capturing the results of the week and charting a path forward gave our team a basis to benefit our field over the coming months and years. Do not risk the progress you have made by believing you will remember everything that occurred during the sprint. Hold a concluding discussion and make detailed notes and slides that capture all the valuable input from the week. Make the learning and progress explicit.

Postsprint Reflections

The design sprint requires an openness to nuance and to reconsidering our own individual design philosophies. During our sprint week, team members were exposed to many new ideas and approaches, and as a result, we experienced lasting unexpected benefits. We perceived, adopted, and adapted to these ideas, coalescing our shared experience into a new and dynamic team culture.

Our success with the design sprint suggests an alternative approach for other scientists—a radically interdisciplinary one—in which the intersection of disparate disciplines (i.e., science and design) can yield new and innovative outcomes. This is new territory for many scientists, but I hope it will spur the kind of progress for others that we witnessed firsthand in our group.

Acknowledgment

Our team would like to thank the International Space Science Institute, Bern, Switzerland, for providing financial support, meeting facilities, and generally fantastic support of the Earth and space sciences.

Author Information

Ryan McGranaghan ([email protected]), Atmosphere and Space Technology Research Associates, Louisville, Colo.

Citation:

McGranaghan, R. (2019), Eight lessons I learned leading a scientific “design sprint”, Eos, 100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EO136427. Published on 11 November 2019.

Text © 2019. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.