Research & Developments is a blog for brief updates that provide context for the flurry of news that impacts science and scientists today.

An annual United Nations report, published 29 October, reveals a “yawning gap” between existing and necessary climate adaptation finance that is “putting lives, livelihoods, and entire economies at risk.”

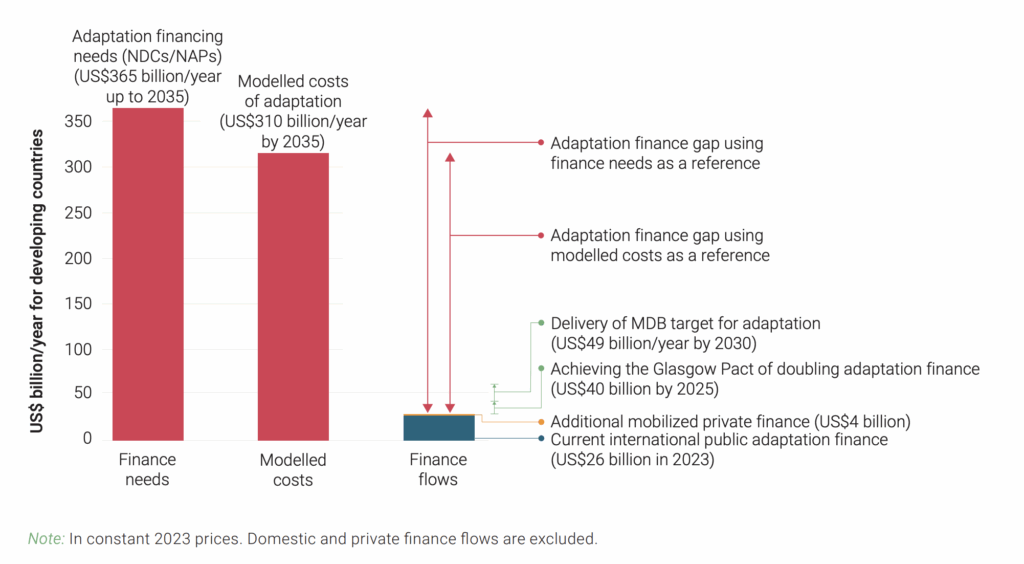

Adaptation needs in developing countries—estimated to be at least $310 billion per year by 2035—are 12 times higher than current public international finance flows, which currently sit at about $26 billion per year.

This so-called adaptation gap limits poor countries’ ability to withstand the changing climate, the report states.

Poorer countries are often the hardest hit by the effects of climate change, despite emitting just a fraction of the world’s greenhouse gases. These countries rely on funding from other countries, from both public and private sources, to finance climate adaptation efforts.

“We need a global push to increase adaptation finance—from both public and private sources—without adding to the debt burdens of vulnerable nations,” said Inger Andersen, the executive director of the UN Environment Programme, in a press release. “Even amid tight budgets and competing priorities, the reality is simple: If we do not invest in adaptation now, we will face escalating costs every year.”

“New finance providers and instruments must come on board.”

The report credits the difficulty of mobilizing necessary financial resources to “current geopolitical tensions and cuts to overseas development assistance, among other factors.”

The Glasgow Climate Pact, an international agreement adopted in 2021, set a goal to double international public adaptation finance by 2025. The goal will not be met under current trajectories, according to the report. The most recent climate finance target of $300 billion per year by 2035, agreed upon at the UN climate change conference last year, COP 29, is also insufficient to meet the adaptation needs of developing countries.

A failure to meet international finance goals means “many more people will suffer needlessly,” Andersen wrote in the report. “New finance providers and instruments must come on board.”

“The smart choice is to invest in adaptation now,” she wrote.

The report did include some silver linings: The adaptation finance gap is slightly smaller for Least Developed Countries, the UN’s classification for low-income countries facing severe obstacles to sustainable development, and Small Island Developing States. Additionally, in-country progress to plan for climate change is improving: 172 countries have at least one national adaptation strategy in place, while 21 others have started developing one.

However, the world is failing to reach other climate goals: Another UN report, published 22 October, found that oil and gas companies are still vastly underreporting their methane emissions. And ahead of COP30, scheduled to be held next month in Belém, Brazil, only 64 of the 195 nations party to the Paris Agreement have submitted their required updates to their emissions plans.

The new report is expected to inform discussions at COP30. The Brazilian presidency of COP30 has called for the conference to be a “mutirão global,” a global collective effort, to achieve ambitious climate action. In the report, authors advise nations attending the conference in Belém to transition away from fossil fuels, engage additional financial system stakeholders, and avoid expensive but mostly ineffective maladaptations such as seawalls or wildfire suppression.

In a recent interview with The Guardian about COP30 priorities, Secretary-General of the UN António Guterres said the world has “failed to avoid an overshooting above 1.5°C [2.7°F] in the next few years” and urged swift action.

“It is absolutely indispensable to change course,” he said.

—Grace van Deelen (@gvd.bsky.social), Staff Writer

These updates are made possible through information from the scientific community. Do you have a story about science or scientists? Send us a tip at [email protected].