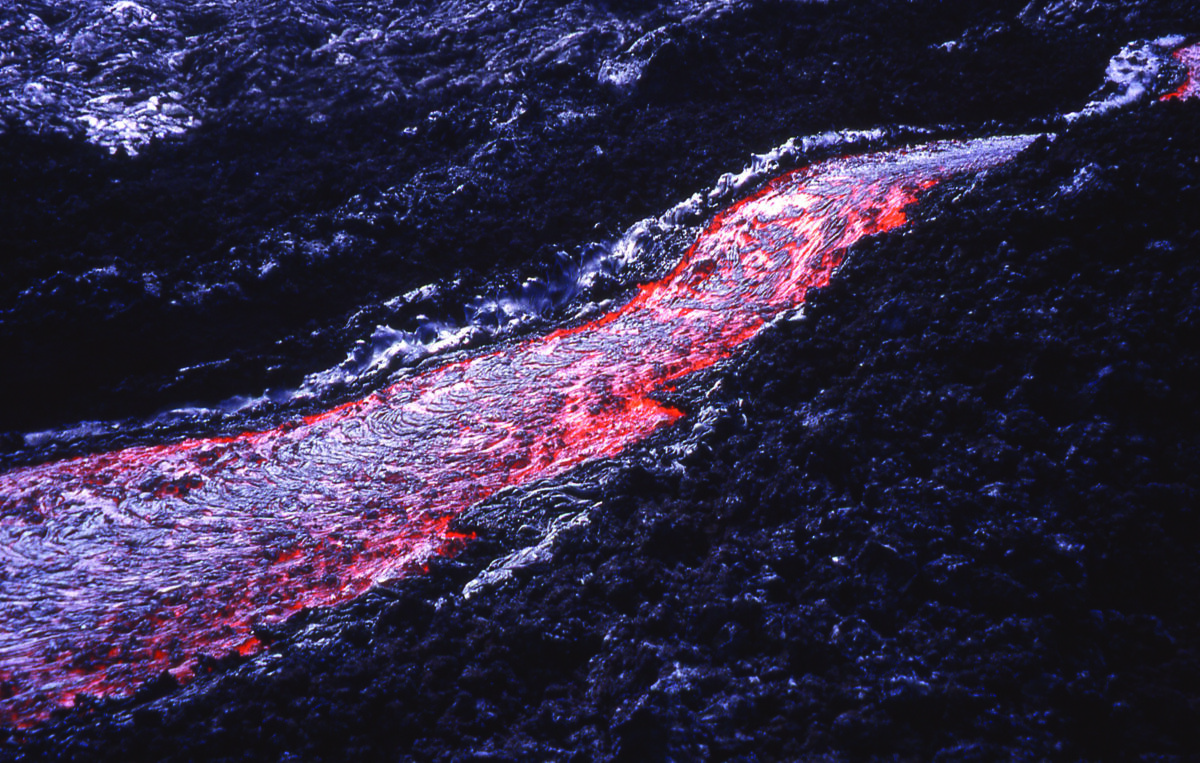

As soon as lava flows from a volcano, exposure to air and wind causes it to start to cool and harden. Rather than hardening evenly, the energy exchange tends to take place primarily at the surface. The cooling causes a crust to form on the outer edges of the lava flow, insulating the molten lava within. This hardened lava shell allows lava to travel much farther than it would otherwise, although cracks in the lava’s crust can cause it to draw up short.

When there is a break in the terrain—a sharp change in slope, a valley, or a rock wall, for example—smooth lava flow is disrupted. Pulses in flow volume or the formation of turbulent eddies caused by these topographic features can make the hard lava shell crack. Using observations from historical eruptions and a simple mechanical model, Glaze et al. studied how changes in slope can affect lava flows.

The increase in flow velocity from a steepening slope is often quite minor, as most of the energy goes into vertical rotation of the lava, just as with a rock rolling down a hill. The authors’ model considers factors such as temperature, depth, and flow velocity, along with the effect of lava viscosity, to calculate how a change in slope affects the formation of vertical eddies created by tumbling lava. The model allowed them to determine how far downstream the turbulence persists before the lava returns to a more streamlined flow. (Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, doi:10.1002/2013JB010696, 2014)

—Colin Schultz, Writer

© 2014. American Geophysical Union. All rights reserved.

© 2014. American Geophysical Union. All rights reserved.