Source: Paleoceanography

Globalization, the close interaction of forces around the globe, is typically thought of as a relatively recent concept. For Earth’s oceans, however, the phenomenon is as old as the sea. Water flow around landmasses and underwater topography builds up into large currents that define our oceans. As landmasses have shifted throughout history, ocean currents have shifted along with them.

To understand those shifts, Fontorbe et al. used marine microfossils in ocean sediment to trace ocean currents from the Oligocene and Eocene eras, between 50 and 25 million years ago.

The researchers focused on an area in the central Pacific Ocean, near Hawaii. They collected microfossils from sediment cores and isolated samples from sponges, which occupy the seafloor, and radiolarians, or protozoa that live in the first 200 meters or so of the water column—the part illuminated by sunlight.

By examining the ratios of silicon isotopes these organisms took up from their environments, scientists can determine the concentrations of silicon dissolved in the water around them. Newer deepwater formations contain less dissolved silicon than older ones, so a sharp change in silicon concentration in an area could indicate a shift in where its water is coming from.

Around the transition between the Eocene and Oligocene, between 37 and 34 million years ago, isotope ratios from both radiolarians and sponges suggest a shift from low to high silicon concentrations.

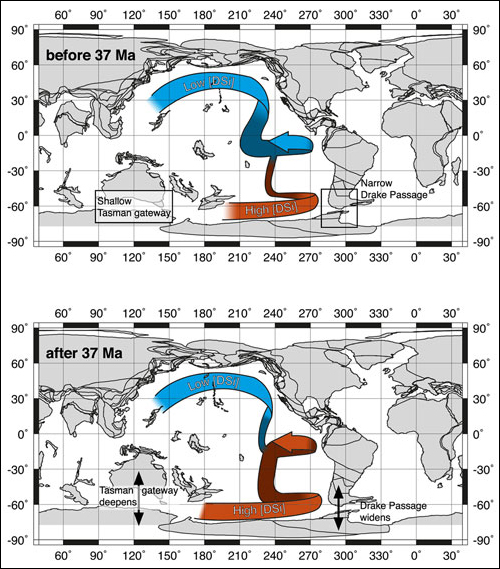

This period was also a tumultuous time for Earth. Volcanism and meteorite strikes, tectonic shifts, and a changing climate combined to alter ocean currents. Previously, the southern part of the Pacific Ocean was relatively closed in, and the stronger currents from the north fed the Hawaii region. However, about 37 million years ago, Antarctica and the southern tips of Australia and South America drifted apart, opening up greater circulation in the Southern Hemisphere. The new influxes strengthened the southern currents, driving their silicon-rich waters northward into the central Pacific.

The team’s results align with previous research on Pacific currents, and they help paint a fuller picture of the shifts in the ocean’s past. Ocean currents play a critical role in climate, weather, and nutrient transfer. The researchers’ findings about the currents of the past will help us better understand how the oceans flow today. (Paleoceanography, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017PA003090, 2017)

—Elizabeth Thompson, Freelance Writer

Citation:

Thompson, E. (2017), Microfossils illuminate ancient ocean currents, Eos, 98, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO084739. Published on 23 October 2017.

Text © 2017. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.