Scientists play a special role in legal debates and public policy decisions. The challenge for scientists who serve as expert witnesses is to communicate effectively in various legal forums, including litigation and legislative hearings. Expert witnesses must not advocate for one side or the other but must be able to convey the meaning as well as the quality and accuracy of their work.

To be effective communicators, expert witnesses need to be familiar with the legal system and the role lawyers play.

At a basic level, expert witnesses need to explain themselves and their science to people who are not scientists and who lack understanding of complex scientific principles. They also must understand the complex scrutiny that they are under when they testify at trial or participate in public policy discussions. To be effective communicators, they need to be familiar with the legal system and the role lawyers play.

To serve as an expert witness at trial, for example, scientists must first be qualified through a complex set of legal procedures and undergo direct examination and cross-examination. This involves a thorough examination of credentials, scholarship, and work products such as blogs, public talks, or other statements or materials typically used as resources in similar lawsuits or related legal forums.

In response to the growing opportunity for climate scientists to inform public policy and educate decision makers in high-stakes litigation, lawyers and scientists have come together to develop a unique training program for expert witnesses. Since 2011, the Expert Witness Training Academy (EWTA) held a 1-week training workshop each August at William Mitchell College of Law, an independent law school in St. Paul, Minn.

The Expert Witness Training Academy

The primary goal of the project is to help scientists become better communicators and educators regardless of whether they ever become an expert witness. Each workshop includes scientists as participants (see Figure 1) and a faculty of judges, attorneys, and scientific experts who train the scientists to communicate effectively in a variety of legal forums. Participants in the workshops have been selected across a breadth of professional experiences in the sciences (early, middle, and late career) and through recommendations of previous workshop attendees.

The workshops train scientists to become familiar with the legal processes relating to expert testimony—the legal terminology, the constraints of legal evidence and argument, and the analytical process and values of decision makers in legal and other forums. Through this training, the workshops provide a forum for scientists to learn how to communicate technical scientific data, interpretation of data, and extrapolation from data in court and other legal forums, without compromising the integrity of the research or straying from ethical and legal principles.

In total, 64 scientists have participated in the EWTA workshops. The program is funded by the Paleoclimate Program at the National Science Foundation (NSF), which covers all participant costs. The financial support from NSF has also made possible the development of online training resources that are available to past participants of the workshop (known as EWTA Fellows) through a dedicated portal (see https://web.wmitchell.edu/expert-witness-training-academy/).

Workshop Design

The EWTA workshops are grounded in extensive research and experience in educating adults to be clear and effective communicators. Each workshop is limited to just 20–25 scientists to ensure that every participant receives one-on-one instruction and coaching.

The workshop methodology applies two core assumptions: scientists learn best by doing rather than just listening and observing and scientists more fully understand the role and responsibilities of expert witnesses by also learning about and playing the role of lawyers (see Figure 1).

Learning by Doing

“I had no idea what I was getting myself into—but I am sure glad I did it.” This is a common sentiment of participants during the workshops. Rather than using lectures and PowerPoint slides, which many participants may have expected, participants in EWTA workshops actively participate with hands-on, interactive exercises.

Each participant plays various roles in an elaborate simulation, which is loosely based on the 1972 Rapid City flood, where record rainfall occurred just after controversial cloud-seeding experiments were conducted by defendants in a subsequent lawsuit. The simulation forces participants to answer questions about cloud seeding, massive rainfall, and who is responsible for the disaster.

Through this exercise, participants assume the role of experts in various mock legal proceedings that stem from the flood, including a legislative hearing, depositions, arbitration, and a full-fledged trial complete with a jury played by local community members. Along the way, participants receive feedback from the faculty and watch video of their individual performances.

Participants are coached extensively on how to communicate their science in these various arenas while learning the nuances of explaining scientific information to lay audiences (lawyers, judges, jurors, and legislators). The many different venues and opportunities for performance during the week-long workshop provide participants the opportunity to experiment and practice what works best for them in a given context.

Beyond Expert Witnesses: Learning by Role-Playing Lawyers

In EWTA workshops, participants not only practice and play the role of expert witnesses but also practice and play the role of attorneys. By taking on these roles, participants see the logic and perspective of the lawyers, judges, and jurors in various forums and develop a deeper understanding of effective communication in different legal processes.

Through role-play the participants practice and role-play the fundamental skills lawyers use in litigation and public policy, including making opening and closing statements, direct and cross-examination, taking and defending a deposition, arguing pretrial motions, and even planning and conducting a full-blown trial. The workshops make use of courtrooms and video review rooms at William Mitchell, which are used for training law students and lawyers.

The reason for providing scientists an in-depth understanding from both the lawyer’s and witness’s perspectives is simple. Scientists may know about trials from television or personal experience, but they may not be aware of the complexity and breadth of the use of experts or the roles and purposes of other legal proceedings, including pretrial motions, arbitrations, negotiations, and congressional and public hearings. For example, they may not fully understand the rationale behind a lawyer’s line of questioning until they have been asked to be the lawyer developing that line of questioning.

In addition to better understanding the lawyer’s perspective, training in the skills of lawyering provides participants with the opportunity to continue to work on their communication skills. By honing their presentations at a mock legislative hearing, for example, participants practice making clear, understandable statements to lay audiences, judges, and elected officials, a key skill for their potential postworkshop roles as expert witnesses.

Preliminary Results and the Future of EWTA

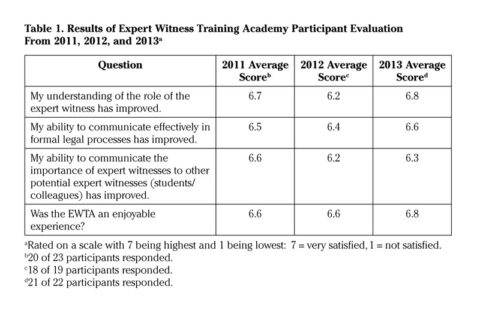

At the conclusion of each workshop, participants complete an evaluation of the EWTA program. On the basis of the results for every single category in the evaluation, the EWTA workshops were successful and received high ratings. In addition, participants overwhelmingly said they would recommend the workshop to their colleagues (see Table 1). The combined overall rating for the three workshops held in 2011–2013 was 6.7 out of 7.0 (59 of 64 possible respondents).

These preliminary results suggest that the process of helping scientists communicate more effectively as expert witnesses requires hands-on, experiential learning activities. The results also indicate that there is value in learning and practicing lawyering skills while simultaneously developing the craft of being an expert witness. In addition, the evaluations show that through the EWTA, participants can better understand and appreciate the perspectives of major players in the courtroom and in public policy debates.

The process of helping scientists communicate more effectively as expert witnesses requires hands-on, experiential learning activities.

Funding is already in place through NSF for another EWTA workshop in August 2014. The design team is also planning to expand the workshop’s format to include other branches of science, complete with discipline-specific simulations for training future participants. Information and updates on future developments for the EWTA will be available at https://web.wmitchell.edu/expert-witness-training-academy/.

—Jim Hilbert, John Sonsteng, and Linda Thorstad, Expert Witness Training Academy, William Mitchell College of Law, St. Paul, Minn.; email: [email protected]

Citation: Hilbert, J., J. Sonsteng and L. Thorstad (2014), Effective communication in legal and public policy hearings, Eos Trans. AGU, 95(15), 125, doi:10.1002/2014EO150001.

© 2014. American Geophysical Union. All rights reserved.

© 2014. American Geophysical Union. All rights reserved.