At the 2006 American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in St. Louis, Mo., we happened upon a session about the “Café Scientifique” approach to engaging the public with science and scientists. Café Scientifique programs—also known as science cafés—combine two essential ingredients. First, they take place in a collegial social setting like a coffeehouse or restaurant where participants can interact with a scientist and each other. Second, they satisfy participants’ curiosity about a science-based topic via conversation with a scientist. It is this blend of the two interactive ingredients that accounts for the Café Scientifique model’s growing popularity—from grassroots beginnings in England, it has grown to include nearly 400 organizations around the world.

We thought this was a splendid idea indeed, and it led us to wonder whether this might be a good way to connect science and that hard-to-reach segment of the public, the high school teenager. With a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), we began the experiment in four northern New Mexico towns with very diverse ethnic, socioeconomic, and population characteristics: Santa Fe, Los Alamos, Albuquerque, and the tiny town of Española.

Our primary goal was for the teens to increase their understanding of the nature of science and to develop a realistic perception of scientists and the lives they lead—which they typically do not get in school. We wanted to get across to the teens that a scientist is a real, complex, multidimensional human, like them. We wanted our presenters to convey that they are leading particularly interesting lives in science. We wanted to instill an appreciation of the relevance of all kinds of science to the students’ own lives.

Our secondary goal was to help our scientist-presenters learn to effectively communicate the fruits of their own research to the public—especially our particular segment of the public, which, frankly, many scientists find to be intimidating!

We are now in the ninth season of Café Scientifique New Mexico (Café NM). As the details of our Teen Café model have been refined through trial and error over the years, the program has proven increasingly popular with the teens for much the same reason that adult science cafés are popular.

Teens find interaction with scientists interesting, fun, and eye-opening—the café has changed their view of the importance of science to their lives.

Our evaluations tell us that we have been successful. From the summative evaluation, “analyses indicate that the Café program succeeded at positively influencing attitudes about science. All the items designed to measure attitudes towards science, scientists, and science-based careers showed statistically significant differences between the participant and non-participant groups.” The evaluation results show that teens find interaction with scientists interesting, fun, and eye-opening—71% of respondents agree that the café has changed their view of the importance of science to their lives.

Teen Science Café Network

As a result of the success and maturity of our Teen Café model—and interest in other organizations in starting their own Teen Café programs—we got new funding from NSF to develop a network of such programs around the country. The Teen Science Café Network started its first season with five founding member organizations.

Now in its fourth season, the program has grown to more than 40 sites around the country, from Alaska to Florida and Maine to Texas. Each node in the network has applied the model with a delightfully unique flair appropriate to local institutions and demographics. Some of the nodes run cafés in multiple local venues, including museums, office parks, community centers, and churches. They have achieved a high degree of diversity by holding cafés where teens are, in the unique ethnic and social environments of their own communities, rather than having attendees travel to a central location.

Our Teen Café topics have covered a wide range, from belly button biodiversity to cybersecurity.

Our Teen Café topics have covered a very wide range, from belly button biodiversity to cybersecurity to flocking behavior of birds to a day in the life of a teen dolphin to corals on acid to emergency room medicine to alternative-fuel cars. Presenters have come from a great variety of local institutions, including universities, research labs, and businesses.

Most nodes in the network offer cafés on the whole range of topics in science, engineering, and technology, but programs may focus on one discipline. For example, the Florida node focuses on ocean science; a new hospital-based node just coming on will focus on medical science. A program could well have a disciplinary focus in any area of the geosciences, such as tectonics, hydrologic science, or space physics.

There are other secrets of success associated with the teen audience. One is that the teens achieve a sense of ownership of the program through forming teen leadership teams at each site. We encourage the teens to lead all aspects of the program to the greatest extent possible, with adults in the background for support.

Another is that although we have deliberately avoided holding cafés in schools, we have made a point of building relationships with high school teachers, who have proven supportive and helpful in innumerable ways. And a third is that in every café, we work with the presenter to develop some sort of activity that the teens can engage in to complement their interaction with the presenter—teens like to do stuff.

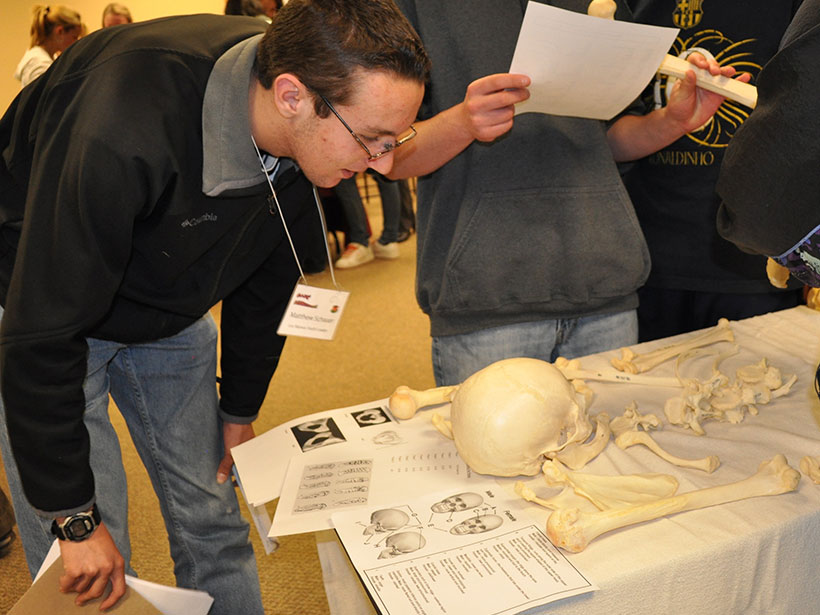

Hands-on activities that actively engage the teens help to cement the science message. Activities can include examining artifacts to answer a question, handling or observing live animals, competing in team games like cybersecurity or robotics challenges, and taking Jeopardy-like quizzes. Activities can even engage the whole body, where students simulate the movements of animals or seismic waves.

How to Talk to Teenagers (About Science)

The degree of engagement needed to spark interest in science topics—especially for the teen audience—is unfamiliar and daunting to many café scientist-presenters, even those with experience in public speaking. Most have been trained to approach science communication in the “information deficit” mode, that is, “stuffing” the audience with information they think the audience needs without any attempt to interact and determine whether the audience understands the information or finds it meaningful. However, with coaching from the program staff and after some initial trepidation, the scientists typically rise to the occasion.

We begin this process by identifying potential café presenters within our local science organizations, looking particularly for scientists working in areas that our teen leaders have expressed interest in hearing about. We then carefully vet the potential presenters and have informal conversations in which we convey the essential ingredients of a successful café.

To help the speakers, we provide them with a guidance document intended to formally frame the process for preparing and conducting the café sessions. The document stresses the importance of knowing the audience. Teens will readily engage with a presenter on some hot science topic if it is accessible to them; hence, the presentation needs to be free of jargon. We encourage presentations organized around one essential provocative idea or concept, where presenters tell a story but leave some mystery in the story.

A Teen Café—like a classic adult science café—needs to be a conversation, not a lecture.

We also stress that interactivity is one of the most important ingredients of a Teen Café. In a café presentation, communication—meaning two-way verbal interaction, supported by a few simple graphics—is of the essence. A Teen Café—like a classic adult science café—needs to be a conversation, not a lecture.

Practice Makes Perfect

We have found that it is highly valuable—and indeed essential—for presenters to do a dry run with a small group of teen leaders before presenting to a full house. This has proven exceedingly valuable in getting the presentations pitched at the right level and the graphics comprehensible. It also serves to overcome a certain intimidation factor for many presenters.

The attitude of this presenter about the value of the dry run is typical: “The dry run was immensely valuable. It helped me select appropriate verbiage and content for the presentation. It also helped me gauge the level of delivery….After the dry run, I made significant changes to the presentation, including the elimination of confusing content, identification of real-world connections, and simpler examples.”

Café NM has had more than 80 presenters. Without exception, they enjoyed and valued their experience engaging with teens, improving and broadening their communication skills.

Some have also benefited in an unexpected way: They have come to a new perspective on their own research. As an added benefit, the Teen Café program can be a vehicle for community outreach and for satisfying the “broader impacts” requirements of the scientific funding agencies. As one presenter put it, “The Café experience was beneficial to me as a scientist in that preparing an interactive talk for an audience of young people helped me identify the critical issues in my work: why I was doing it, why it is challenging, what we are trying to accomplish (vs. being bogged down in technical details). This really focused my thoughts about my work.”

Expanding the Network

Rather than being a collection of static, independent entities, network nodes are part of a dynamic network, a community of practice with active sharing of lessons learned, documents, images, videos, ideas for café topics and formats, expertise in social media, and many other resources. We want the network as a whole to be much greater than the sum of its parts. Any organization wishing to start a Teen Café can do so by registering on the Teen Science Café Network website and agreeing to adhere to six core design principles.

We expect the network to grow steadily over the next few years. At the Teen Science Café Network, we have resources to help others start a Teen Café, and it is part of the ethic of the network that existing members will actively help new members start and successfully run Teen Café programs. One member commented, “The commitment by the TSCN Program to ‘support and freely share expertise with new groups wanting to start TSCNs’ has been so impressive. Every time I had a question or concern about how we might do something or how to make the program work for our specific situation, I heard from several different people. They were extremely generous with their time and very helpful.”

Author Information

Michael Mayhew and Michelle Hall, Science Education Solutions, Los Alamos, N.M.; email: [email protected]

Editor’s Note, 21 September 2016: Forensic anthropologists fiercely debate whether certain characteristics can be determined from skeletal remains. Thus, the main image caption was simplified to avoid invoking such debates.

Citation: Mayhew, M., and M. Hall (2016), Teens and scientists come together at science cafés, Eos, 97, doi:10.1029/2016EO044345. Published on 12 April 2016.

Text © 2016. The authors. CC BY-NC 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.